** All Text on these chapter pages has been copied verbatim – with permission – from this book: “Shurtleff Family Genealogy & History – Second Edition 2005” by William Roy Shurtleff & his dad, Lawton Lothrop Shurtleff ** Text in pdf convert to word doc – any spelling errors from the book may or may not have been fixed. **

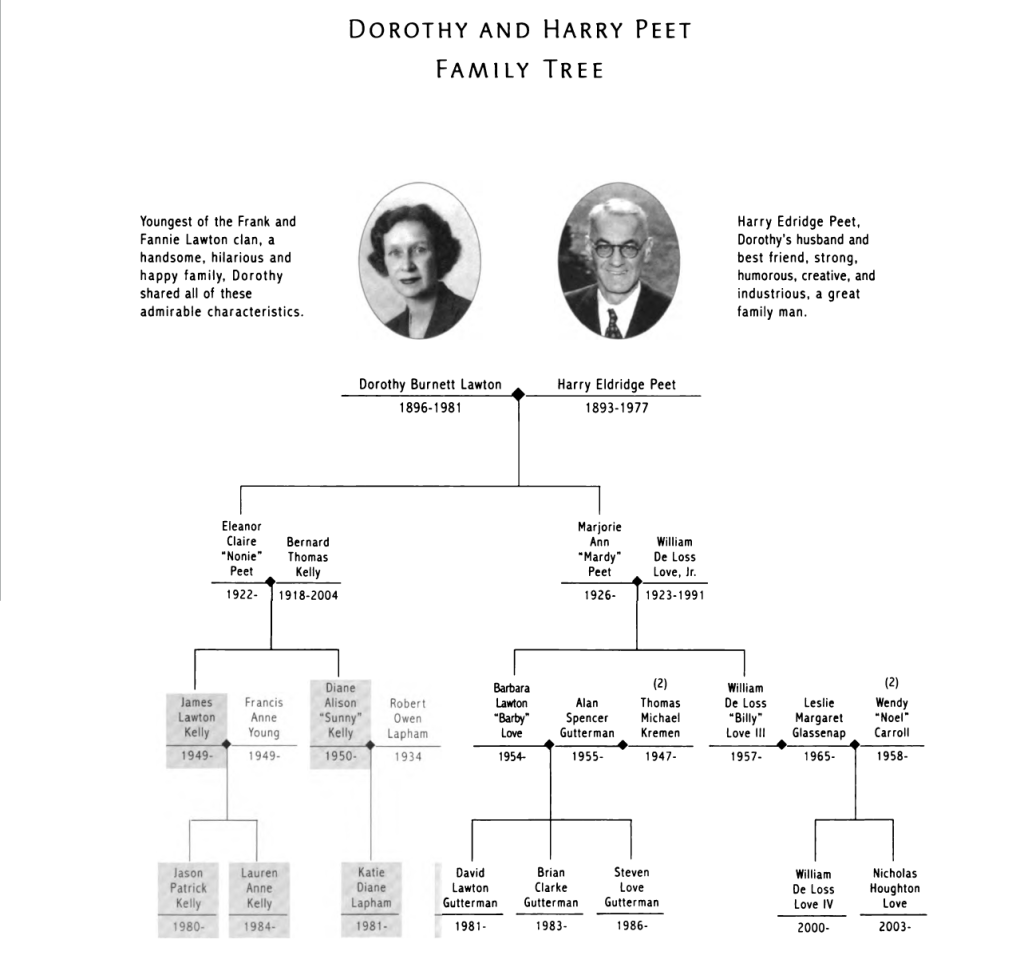

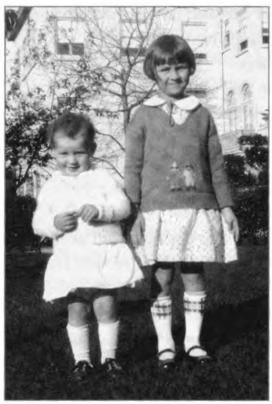

Growing Up in Berkeley. Dorothy Burnett Lawton was born on 3 August 1896 in Berkeley, California. The youngest of seven children, she was born at her parents’ home at 2211 Durant Avenue. Her middle name came from Judge Burnett of Santa Rosa with whom her mother, Fannie, had stayed during Fannie’s college years. As a child she was called “Dot,” a name later used by her immediate family and very close friends. Everyone else, including her husband, called her Dorothy—as will we here.

It was no secret that Dorothy was the apple of her father’s eye and a spoiled child. He made the older children angry by allowing her to eat only what she wanted (especially tamales and spicy hot Mexican food), while the others ate what was served them. Harry Lawton, throughout his life, referred to Dorothy affectionately and jokingly as “my spoiled little sister.”

Dorothy went to McKinley Grammar School in Berkeley, then on to Berkeley High. Her health was not strong, and she was allowed to miss part of a couple of semesters in grade school because of some vague, undefinable illness.

With five older brothers and sisters, Dorothy must have been somewhat of a “tagalong,” but in such a supportive family everyone did their best to include her in family activities. Don, who was closest to her in age, remembers how, as a little girl, Dorothy would ride with him on the back seat of his hook and ladder fire wagon, while he drove the billy goat that pulled it around Berkeley.

In the diary that Helen Lawton wrote from 1909 to 1911 (when Dorothy was 12-14 years old), Helen mentioned Dorothy at least 33 times, usually describing places they went and things that they did together. For example, they went out driving in the evening with their father, slept overnight on the Witter’s porch, went in the buggy to visit Uncle Charlie, went to the “moving pictures show” (several times), went to Idora Park, went uptown with Papa to get some ice cream, played cards on a rainy day, went to Cal, saw Sarah Bernhardt in Phaedra, and heard Woodrow Wilson speak.

We also learn that Dorothy had a light touch: “She had had on a pair of pajamas to represent a Chinaman. They looked comical.” She was enough of a tomboy that she could chin herself in the backyard, which impressed Helen. She belonged to a reading club outside of school, took piano lessons and attended a dancing school (both together with her brother, Don), and in high school was in the Alpha Sigma sorority, as Helen had been. Her elder sister, Hazle, was a Pi Phi. She went to Christian Science church a few times with Helen and her friends, but never became as interested in Christian Science as Helen, Winnie, or her mother, Fannie.

Many of Dorothy’s girlfriends from her early days remained lifelong friends: Dorothy Morris, who married Dr. Harold Morse, who became the family doctor; Kathryn Green, who married Freddie Du Puy and later lived next door to Dorothy on Tunnel Road in Berkeley; Kathryn Woolsey, who was in the Alpha Sigma sorority at Berkeley High with Dorothy, and married Jim Dorst, a marine colonel (for many years they lived around the corner from Don and Billie Lawton on Parkside Drive) and Helen Peet, the younger sister of Harry Peet whom Dorothy later married.

While she was growing up, Dorothy spent many summers with her family at Monte Rio. There she learned to swim, paddle a canoe, and row a rowboat. She went on to become a very good swimmer, second only among the girls in the family to Helen Lawton. She later taught many of her brother’s and sister’s children to swim at Monte Rio and Lake Tahoe. Her father had a mini rowboat built for her, since she was too little in those days to handle the bigger boats. For many years after Dorothy grew up, that boat continued to be used as the official lifeboat, which was kept tied to the dock at Monte Rio.

Dorothy entered Berkeley High School in 1914 and graduated in June of 1916. It is not clear why she was there for only two years. A nice photograph of her appears in the 01la Podrida (Berkeley High Yearbook). Her major activities are listed as:

“Berkeley Chairman Refreshment Committee High Senior Dances; Chairman Entertainment Committee Girls’ Reception 1914; Social Committee 1914-15; Vaudeville 1915-16; Spring Festival 1915.”

Dorothy kept a photo album from 1915 to about 1924. Unfortunately many of the better, larger photographs were later pillaged.

Though every one of her older brothers and sisters had gone to college (they all went to Cal), which was unusual in those days, especially for women, Dorothy chose not to attend college. She got good grades in high school, but she was never very interested in intellectual pursuits. She was more of a doer. Mardy Love reflects: “I think it always bothered Dorothy that she missed the fun of college, which was much more fun in those days than it is today.” Dorothy is also remembered as having an exceptionally good memory. As a young girl she had everybody’s phone number memorized. Don Lawton, her brother, recalls:

During her last few years in high school, Dorothy wanted to be a trained nurse. We joked about it an awful lot and finally we talked her out of it. She was very smart but she wasn’t that big. We kept telling her, “If you lift those big men in and out of those beds you’re gonna have a bad back the rest of your life.” We thought she was too light-weight for a tough job like that. They made nurses do all kinds of heavy work in those days. It was too much. That is why she didn’t go to Cal like the rest of us.

So after graduating from Berkeley High, Dorothy attended a secretarial school in San Francisco, then went to work for Foote, Cone & Belding, a San Francisco advertising agency, until about 1920.

At some point during her younger years in Berkeley, Dorothy met her husband to be, Harry Peet. No one seems to know for sure how or when they met, but Don Lawton recalls that Dorothy had long been friends with Harry’s younger sister, Helen (who was about her age), and thinks that Dorothy probably got to know Harry through Helen. Since Harry was two and a half years older than Dorothy, and since he graduated from Berkeley High School four years before Dorothy, it seems likely that they started to become close to one another after leaving high school, when age differences gradually assume less importance. It is unlikely that they were very close by the year 1911 (when Dorothy was age 15 and a junior in high school), since Harry Peet is not mentioned in Helen Lawton’s diary, which goes up to June 1911. Yet they could have met while they were children, since the Peet family lived only a few blocks away from the Lawton family and they both went to McKinley Grammar School.

Image: Dorothy with a bridal bouquet, perhaps in preparation for Hazle’s wedding, circa 1913.

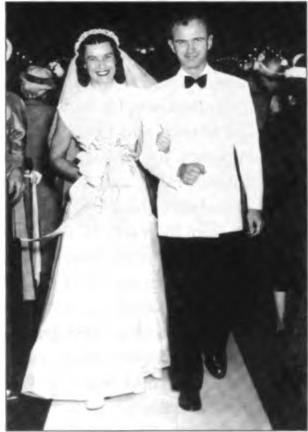

Dorothy was married to Harry Eldridge Peet on 14 August 1920 in Berkeley, California in the Lawton family home at 2211 Durant Avenue. Those present included Bimelyn Seymour and Don Lawton. Dorothy’s bridesmaids may have included Dorothy Morse, Helen Peet, or her sisters.

Nonie Peet Kelly recalls:

The honeymoon got off to a slow start when the couple borrowed a car from Harry’s father. This four-door convertible [perhaps an Apperson “lack Rabbitl broke down in Richmond on their way from Berkeley to Tahoe. Dorothy told us about sitting at a garage on an oil drum writing thank-you notes, while Harry and a mechanic worked on the car. By about 10 o’clock at night they had to give up. They called Frank Lawton, Dorothy’s father, to come and get them—since there was no place to stay in Richmond. They returned to the Lawton family home in Berkeley and the next day—probably with Don Lawton’s help—they got the car fixed and were on their way again.

On the return from Tahoe, coming down the Myers Grade, they were horrified to see their own wheel from the left rear of the car passing them on a turn, then rolling off the road and down into a canyon. Dorothy remembered her low morale when Harry said, “I’ll go try to find the wheel if you’ll go back and find the cotter pin.” Much to their surprise, they each did!

Though she was the youngest child, Dorothy was not the last to marry; both of her brothers, Don and Harry, married after she did.

Harry Peet and His Ancestors. Henry Clay Peet and Cordelia Irene Belle Williams were Harry Peet’s parents. Clay (as he was usually called, though he was known in the the family as “Pa Peet”) was born on 23 January 1867 in Columbus, the capital of Bartholomew County, Indiana, the son of Charles Peet and Mary Goodin. Cordelia (Cordie) was born on 30 October 1870 in the same place, the daughter of Newton Williams and Ms. Silvers. Nonie Peet Kelly thinks that Cordie may have grown up on a farm in Pennsylvania. Her family’s farm backed up to a Poor Farm; Cordie always saved her pennies so she wouldn’t have to go to the Poor Farm. Clay and Cordie were married on 17 August 1890, probably in Columbus, Indiana. Between 1891 and 1895 they had three children: Lenore, Harry, and Helen.

In the mid-1890s the family moved briefly to Chicago, Illinois. Then in about 1905-06 they settled briefly in Los Angeles; Clay had cousins there. Some of them were in the restaurant business and other relations were involved in show business.

Nonie recalls: “I believe an actress named Ina Claire was a cousin. Later, someone who was a film director took us to Paramount Studios for the day where we watched Bing Crosby working on a movie set. Another lady who was an artist painted Jim and Sunny as children.”

Harry had an uncle who he called “Uncle Ellery” Peet who lived in Los Angeles for a while, and who owned two dogs named Tony and Leader. When uncle Ellery died, he gave Harry his dogs and some diamonds.

In 1906 or 1907 Clay Peet and his family moved to Berkeley, California. The 1907 Berkeley City Directory shows them to be living at 2139 Carlton Street. In about 1908-09 Clay began to work for a company named Ellery Arms Co. Inc., a sporting goods company in San Francisco. Since the company appears to have been founded at the same time that Clay began to work for it, he may well have been one of its founders. The company’s earliest appearance in the San Francisco City Directory (1909) shows that the officers or managers were William Ellery, president; George W. Ellery, vice-president and treasurer; H. C. Peet, secretary. Ellery Arms was described as “manufacturers and jobbers of complete outfits for explorers, campers and prospectors, fishing tackle, guns, ammunition, photo supplies, optical goods, and athletic supplies. 48-52 Geary Street.” Clay worked for this company for the next 12 years. By 1918 the company had moved to 583-85 Market Street.

A great outdoorsman and quite a good shot, Clay was right at home at Ellery Arms. His family still has part of a silver demitasse set he won trap shooting at the Olympic Club in San Francisco.

Clay Peet loved to hunt and he often took his son, Harry, and his dogs with him. One of his dogs was a show dog named Leader. They took him one weekend to a benched show in San Jose. He escaped from his bench and disappeared. After spending the rest of the day hunting for him, they finally gave up and returned home to Berkeley. Leader showed up at home about four days later, ragged and bloody. But he had footed it all the way from San Jose to Berkeley and found his home.

Clay Peet and his family moved a number of times during their years in Berkeley. By 1909 they were at 2147 Blake Street, by 1911 at 2023 (or 2025) Parker, by 1914 at 2549 Ellsworth, and by 1917 at 2609 Ellsworth.

In about 1920-21 Clay and Cordie Peet left Berkeley and moved to Orange Cove, near Fresno, California. There they bought land and went into the turkey ranch and orange grove business. Ellery Arms continued to exist as a company in San Francisco. Nonie Peet remembers “Clay and Cordie laughing a lot. That’s all I remember about them together. I don’t even have a picture of them.” I remember Grandma Peet [Cordie] very well; she lived to see great-grandchildren.”

Clay Peet died on 17 March 1927 on his ranch in Orange Cove. He was 60 years old and apparently in fairly good health. According to his death certificate, the cause of death was “rupture of the heart caused primarily by over exertion while cranking a tractor.” Strangely, there are various stories of how he died. Don Lawton believes that Clay was killed in an accident when his tractor overturned. Lawton Shurtleff recalls:

In the Roy Shurtleff family we were always told a story I will never forget. Pa Peet, a hardworking farmer, came in one mid-afternoon on a scorching day, opened the ice chest, took a big drink of cold water, lay down on the couch to rest, and never got up. To us, the message was not to drink too much cold water on a hot day.

Mardy Peet, Clay’s granddaughter, has also heard to this day that her grandfather had died from drinking cold water. Perhaps he overexerted himself on a hot day cranking the tractor and then came indoors and drank too much cold water.

Cordie moved back to Berkeley and lived with her youngest daughter and her son-in-law, Helen and Ed Hussey, at 612 Mariposa Avenue. She lived as a widow for the next 27 years. She died on 29 October 1954 in Berkeley, California.

Don Lawton remembers that “Pa Peet was a real gentleman.” Lawton Shurtleff adds: “Ma and Pa Peet were exceptional people: genuine, honest, fair, and open, almost like a Norman Rockwell painting. They were simple, pure farmers, very lean and slim, with these big jut jaws. Harry was similar in many ways.”

Clay and Cordelia had three children:

- Lenore Peet was born on 23 Aug. 1891 in Columbus, Indiana. She never married. She held a number of jobs as a young woman: In 1910 she was working as a saleswoman, in 1913 as a clerk, and in 1914 as a milliner. Then by 1917 she had decided on a profession, for she was listed as a student nurse at Merritt Hospital in Oakland. By 1918 she was a full-fledged nurse, and she remained so for most of the rest of her life. Though she continued to live in Berkeley for a while after her parents moved to Orange Cove (she was at 5825 Keith Avenue in 1923 and 5335 Boyd Avenue in 1926) she worked as a nurse in San Francisco. In 1943 we find her living with her mother, Cordie, in Oakland at 4130 Montgomery St. She died on 5 May 1972 in Oakland.

- Harry Eldridge Peet was born on 18 Feb. 1893 in Columbus, Indiana. His story is told in full below.

- Helen Peet was born on 8 Nov. 1895 in Chicago, Illinois. She grew up in Berkeley, working as a teacher in 1915 and a stenographer by 1917. She married Edward K. Hussey 20 May 1922. He was born on 29 Aug. 1888. Helen and Ed had two children:

- Janet Hussey was born on 26 June 1923 in Oakland, Califomia. She married John Viney on 13 Jan. 1948. He was born on 18 April 1922. They had five children:

- – Robert Michael born on 19 Dec. 1948.

- – James born on 2 Nov. 1950.

- – William born on 23 March 1952.

- – Gregg born on 4 Dec. 1954.

- – Cheryl Anne born on 18 Feb. 1956.

Barbara was born on 11 Aug. 1925, in Oakland. She married Warren Brownell on 1 Feb. 1947. He was born on 12 Feb. 1920. They also had five children:

- – Philip born on 27 Dec. 1947.

- – Catherine born on 2 May 1950.

- – Mari born on 29 Sept. 1951.

- – Timothy and Jeffrey (twins) 10 July 1953.

The Husseys lived in Oakland at 612 Mariposa and Ed Hussey was an owner of the firm Hussey & Belcher, construction engineers, with offices at 1440 Broadway in Oakland. Edward died on 6 Jan. 1946 at his home on Mariposa in Oakland of cancer.

Three years later Helen remarried to Lee Murray on 7 Aug. 1949. They lived in Berkeley. He died only two years later on 20 May 1951 at home of a heart attack. Helen died later in Maryland while staying with her daughter, Janet Viney.

Harry joined the U.S. Army Cavalry following graduation from U.C. Berkeley, circa 1918.

Harry Eldridge Peet. Born on 18 February 1893 in Columbus, Indiana, he moved with his parents to Los Angeles, California. In later trips to the area he showed his wife and daughters the school where, as a young boy, he had played the triangle for the kids to march in from recess.

Harry’s family moved to Berkeley in about 1906-07 when he was 13-14 years old. He attended McKinley Grammar School and Berkeley High. He and Don Lawton were friends at both these schools. Harry graduated from Berkeley High School in December 1912, in the same class as Guy and Elizabeth Witter, six months after Helen Lawton, and exactly two years before Don Lawton. He looked trim and handsome in the 011a Podrida yearbook of December 1912. Virtually all of his major high school activities took place during his senior year: “011a Podrida Staff, 1912; Vaudeville Show, 1912; High Senior Concert, 1912; Senior Play Cast, 1912; Properties Committee Senior Play, 1912; Decoration Committee Senior Ball, 1912.”

Don Lawton has clear memories of Harry from his early years:

When I was at Berkeley High, Harry was an upper-Glassman. He had an old Duck motorcycle and so did I. (But Don got his Duck in 1913!). Harry and a friend named Brud Montgomery used their motorcycles to deliver baked goods for the Dwight Way Bakery] at Shattuck and Dwight Way] and to do a paper route. We would meet almost every evening and race on the streets around Boon’s Field, the Berkeley High School football field. These two cycles made a very loud noise, like a gattling gun, and we just had more fun.

Harry had four or five very close friends in high school, including the Simes brothers (Jack and Harold), Hugh and Vic Sandner from Australia, Jimmy Bretherton, and Clarence Felt. They were all very fine, clean-cut, wholesome, athletic type fellows, and they liked to play basketball together.

Like his father, Harry was very mechanical and interested in mechanical things. He used to work a lot during the summers for his father who was a salesman or sales manager for Ellery Arms Co. He’d clean rifles, wind armatures, and do other work around the shop.

After we graduated, we formed a group of those Berkeley High fellows who went to Cal with the Class of 1918. It was the best association we ever had. Harry and I were both in it. We had a reunion once a year, with everyone having lunch together, for the rest of our lives. We had a grand time renewing old times.

On many a weekend during his junior high school years, Harry and his father would go hunting with Harry’s dogs. They would hitch up their team of horses to the family buggy, drive up and over Old Tunnel Rd., then out to the marshes of the Delta in the Sacramento River. Lawton Shurtleff recalls that Harry loved to hunt. Harry’s daughter, Nonie Peet Kelly, recalls: “Dad really loved the trips, but he hated the shooting of the birds and animals, and having to clean them, pluck them, skin them, and then eat them. As an adult he occasionally went fishing, but he really didn’t like killing.”

Harry’s daughter, Mardy Peet Love, recalls that Harry did very well at Berkeley High, but after graduating he got a job for two years in San Francisco working for his father at Ellery Arms for low pay. His father said he would not pay Harry’s way through college; if he really wanted to go, he should work to pay his own way.

After the two years, however, Harry enrolled at U. C. Berkeley and his father helped him pay his way. Both he and Don Lawton entered Cal at the same time, in the class of 1918, and played interclass football on the same team. Harry joined the Dwight Men’s House Club (an alternative to a fraternity). His main fields of study were electrical engineering (so listed in 1915) and commerce, with a lot of mechanical drawing. Lawton Shurtleff recalls that Harry often referred to himself as having been a mechanical engineer. He was in the mandolin club at Cal and also in one other musical group with the class of 1918. He was in his final semester when the United States entered World War I. His daughters recall:

Harry was still in some class like Spanish I—having flunked it before—and not likely to graduate if he couldn’t pass it. Then, because of the war, the university decided to graduate anyone who was in their final semester if they enlisted. And so he did.

All they were accepting at that moment were horse men for the horse drawn artillery or truck drivers for the truck drawn artillery. So he said he could ride horses and drive trucks, and was in. He ended up working both with horses in the cavalry (he learned to stunt ride with one foot on each of two horses) and as a supply officer with trucks. Someplace along the line he was promoted to second lieutenant, and was still in training in New York and New Jersey [Don thinks it was in the South] when the armistice was signed. He was in the same company as Frederic March (real name F. Bikel, later a famous actor), and Irving Berlin, later a famous composer, who was putting on small army camp shows when Dad knew him.

Field Artillery U.S.

Army, circa 1918.

Don Lawton recalls that Harry always used to say jokingly that he was a pilot in the cavalry, because they’d say, “Listen Peet, pile it here and pile it there,” when he cleaned the horses stables!

Harry returned home from the war in about 1919. Shortly after he returned to civilian life, Clay Peet left Ellery Arms and moved with his wife Cordie to Orange Cove, a small farming town in central California about 25 miles southeast of Fresno.

Harry initially looked for work in the Bay Area, then he decided to follow his father to Orange Cove. Don Lawton recalls that Harry bought a house there and opened a Ford agency/dealership with a big garage and machine shop attached. Tom Geen was the head (and only other) mechanic. This business was also into well drilling. But Lawton Shurtleff thinks that all of this “would have taken a great deal more money than Harry had at the time. I thought he opened a small garage handling mostly Ford repairs and parts. Then he came to Thorsen Tool Co. during World War II when labor was so hard to find.”

In Orange Cove Harry met three newly married young men who soon became his close friends. They all had arrived with their brides after the war and tried to make Orange Cove a “growing concern.” Ed Bender was the town banker. He and his wife Adele were both from Reno and had attended the University of Nevada. They became lifelong best friends. Harry Wraith and Nic Scorcer started a small hardware store, in which Harry had a part interest. The newcomers comprised most of the tiny town. Others he met were the Deaver family (Blanch Deaver bought the Peet’s house when they left Orange Cove) and the Pitchards.

Mardy recalls (differently) that Harry and three close friends from Cal (Ed Bender, Harry Wraith, and Nic Scorcer) and their new brides all decided to follow in Harry’s father’s footsteps in Orange Cove.

Pioneer Life in Orange Cove, California (1920-27). After Harry settled in Orange Cove, as noted above, he and Dorothy Lawton were married on 14 August 1920 in Berkeley, at the Lawton home.

Dorothy’s arrival in Orange Cove must have been a culture shock of major magnitude. First, Harry’s dogs, Tony and Leader, treated her like a stranger, growling at her as she came and went, or if she got too near to Harry. Eventually the dogs were sent to live with Clay and Cordie.

The Orange Cove house had a well and a pump and a backyard storage tank up on a platform. Cold water ran into the kitchen and into the one bathroom. Water for a bath (or anything else that required hot water) had to be heated in kettles or pans on the stove then carried into the adjacent bathroom. The big front porch was screened in and the children slept there during the summers.

Image: Harry Peet in front of his and Dorothy’s new home on Regent Street in Berkeley, 1933.

It was inhumanely hot and dry during the summertime. Additionally, none of Dorothy’s family or friends were there.

Adele Bender and Dorothy became best friends and went everywhere together. In order to have a car for Dorothy, Dorothy and Harry built their own. As Don Lawton, an expert on automobiles, who saw the car, recalls:

Harry’s father had this big Haynes touring Car, with chassis and engine but no body or roof. Harry and Dorothy cut off the whole front end with a blow torch and welded on a Model-T Ford front end, with a little Model-T Ford engine and little spindly Model-T Ford front wheels. On the back were the big, heavy Haynes wooden spoke rear wheels. The front seat—there was no back seat—was Harry’s World War I army steamer trunk. Since it had no roof; for shade, Dorothy held up a parasol. It was the funniest looking car you ever saw, half Ford and half Haynes. It was just out of this world! I can just see it now, with that big Haynes rear end sticking up in the air and that little dinky Ford front end, like it was a mole going into a molehill. Later I think Harry put a Ford Coupe body on top of the Haynes chassis.

Nonie Peet Kelly, who was a little girl at the time, remembers her mother’s stories of the car:

Dorothy used to tell us how she spent endless days hand grinding the valves for the engine.

The vehicle did not have a self starter or a dependable idle or neutral. In other words, once the car was hand cranked and started, it started to move. Dorothy always had to have Adele go along with her to do errands, so that Adele could handle the paying out of money as they went to pick up milk or to deliver turkeys or whatever. Dorothy would slow way down and sometimes have to make several passes to complete the business. But if she stopped, Harry or some man strong enough to hand crank it up again had to be sent for. Harry always wished he had a picture of that car.

Not everyone was so admiring. When they drove from Orange Cove to Berkeley to visit Dorothy’s patents, Grandpa (Frank] Lawton was shocked to see his darling little girl, once so perfectly dressed, riding in such a contraption, holding up the parasol. He asked them to kindly park it all the way around back—not to leave it out front or in the driveway.

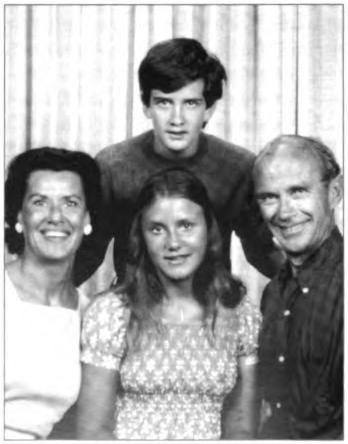

Dorothy and Harry’s first child, Eleanor Claire “Nonie” Peet was born on 3 November 1922 at a nursing home in nearby Orosi, Fresno County About three years later a second daughter, Marjorie Ann “Mardy” Peet was born on 27 January 1926 at home in Orange Cove. Dorothy didn’t have time to make it to the hospital with Mardy. Also the Seventh-day Adventists’ “lying-in” home had harassed them continually for contributions since Nonie’s birth.

Gradually Harry’s main business shifted from selling and repairing Ford cars to installing deep-well electric water pumps. There was very little water in the Orange Cove area. Irrigation was a monumental problem. Since there were no creeks or rivers nearby to supply the town with water, the wells had to be unusually deep. When Harry’s close friend, Alvin (or Alby) Flynn, would drill a well, he would have Harry install the pump. Harry also went to work getting to know the orange-growing and grape-growing businesses. In the latter agricultural ventures, he was working in partnership with his father.

Image: Harry and Doroty, with young Nonie at the Roy Shurtleffs Crocker Avenue home, circa 1922.

It was tough work in those days to make a living in Orange Cove from farming or from providing sales or services to farmers. The town was too small and the perpetual shortage of water became a real problem each summer. During the scorching summers, there was nowhere to go to cool off—no swimming pools or air conditioners, only small fans. The men were among the early workers to plan the Friant Dam project but the actual building did not materialize until years later.

Lawton Shurtleff remembers: “When I visited the Peets in Orange Cove, we cooled ourselves by rolling in farm irrigation ditches and someone always slept in the bathtub because the cast iron metal was so cool. During one stay I recall charging five cents to see tarantulas and grasshoppers, crickets, or beetles fight to death in an old metal wash tub.” Gene Shurtleff also stayed with the Peets once at Orange Cove. He went down by railroad train accompanied by Dorothy Morse, swam in the irrigation ditches, and collected crickets for a circus.

For a couple of years, in about 1925 and 1926, Dorothy spent a week or two each summer with Roy and Hazle Shurtleff at the Brockway resort on Lake Tahoe. The vast, cool mountain lake must have seemed like a heavenly oasis after Orange Cove. Dorothy taught all of the Shurtleff children how to swim, and especially how to do the double overhand crawl she had learned at Monte Rio from her sister Helen. Dorothy was probably one of the few people in the world who was able to shape the tip of her tongue into a three leaf clover. She also taught this little trick to the Shurtleff children, and some of them passed it on to their children.

Nevertheless, Dorothy and Harry looked back on these years as among the happiest ones of their lives. Mardy Peet Love recalls: “They obviously had a ball down there with the other young Cal couples. And this was a whole new world for the spoiled girl.” Nonie adds: “I remember fun times, with Mom and Dad and others dancing on our front porch to the Victrola in the living room. There were happy times and memories of visits. Mom and Dad baby-sat Lawton Shurtleff while his parents, Roy and Hazle, went on some trip in about 1922. Nancy Shurtleff came for a visit in about 1925-26, when she was six or seven years old. The only thing I remember about her visit was the unbelievable fact that she didn’t like carrots (and didn’t have to eat them either). I still can’t get over that.” Dorothy had a ukulele and Harry had a mandolin and guitar. Both played them quite well and often at home.

Regardless of the good times and the good friends, living in Orange Cove gradually became more misery than it was worth. Moreover, after Mardy was born in 1926, the Peets began to think about a place where they would be near good schools. Eventually, one by one, the whole group sold out and moved to the Bay Area. By mid-1926 Harry was looking to expand his electric pump business and to move it back to the Bay Area. On 26 July 1926 Helen Lawton wrote her mother-in-law that “Harry Peet has found a dandy site for the manufacturing of his Ford pump in East Oakland. It is made from all Ford parts.” This company became the Sierra Machine Co.

Raising a Family in Berkeley. In 1927, with children ages one and four, the Peets pulled up roots from Orange Cove and moved back to the Bay Area to start all over again. While looking to buy a house, they rented one for several months at 645 Mariposa in Oakland near Piedmont. This house was across the street and down one house from Helen and Ed Hussey, Harry Peet’s younger sister and her husband, who were at 612 Mariposa. Then in December 1927 the Peets bought a house at 6446 Regent Street in Oakland, only three doors away from the Oakland/Berkeley boundary line.

The Regent Street house was located just two blocks from Helen and Ed Martin and their two children, five blocks from Don and Billie Lawton and their two children, and seven blocks from Winnie and Bernie Seymour and their four children. Nonie Peet was about the same age as Dick Seymour and Ed Martin, and Mardy was about one year younger than Marilyn Martin and Carol Lawton. They immediately became friends, and Mardy and Carol Lawton have been best friends since their first days at John Muir Grammar School. About two years later the Martins moved to Atlanta on business for about six months; Ed Martin opened an office there for Blyth & Co. When they returned, they all moved in with the Peets until they were able to get into their own house on Benvenue.

Almost immediately after Dorothy and Harry left Orange Cove, Harry’s father, Clay Peet, died. Harry returned to Orange Cove, sold everything remaining there, and brought his mother, Cordie, back to live with Helen and Ed Hussey, her daughter and son-in-law. Nonie remembers that “Cordie was still in her 50s and young at heart. She always loved young people around.”

Harry’s first brief job in the Bay Area was with Fairbanks, Morse & Co., a big pump company. He thought he would learn more about the pump business and earn a little money while starting his own pump company. By 1927 he and his old Berkeley college friend, Chet V. Noyes, had started Sierra Machine Company, which made “refrigerating machines” at 6412 San Pablo Avenue on the border between Berkeley and Oakland. Harry was the president, while Noyes was vicepresident and secretary. They designed, manufactured, installed, and maintained large refrigeration systems for restaurants, grocery stores, and food store chains like Piggly Wiggly and Andrew Williams, and drugstores with ice cream and soda fountains. Don Lawton remembers:

Sierra Machine Company soon became a thriving and very successful business, assembling pumps using Ford motor parts such as pistons, rings, connecting rods, and the like. This soon evolved into the refrigeration business. Eventually Harry developed his own type of pump. He got the refrigeration contract with Piggly Wiggly on Broadway and Mosswood Park in Oakland. He laid all the ammonia pipes under the concrete before it was poured, then his pumps pumped the refrigerant. That was his big business for quite a while. Later he did many Piggly Wiggly stores. I think the thing that brought him to Berkeley was the contract with Piggly Wiggly to install the refrigeration system. He also did ice cream stores. I think he understood the refrigeration application in Orange Cove.

Chet Noyes was the big executive type who would sit with his feet up on the desk, smoking a pipe, and give orders. It seemed like he never stopped talking. He’d start work late, have a long lunch, and go home early. . . while Harry did all the hard work. I don’t think Harry was too happy with his silent partner. But I think Noyes put up some money to get the business started.

In those days labor unions were on the rise and Harry had such an emotional struggle with his local union and with the idea that someone else could tell him how to run his business that he eventually got ulcers and had to take ulcer pills regularly.

In about 1930 Harry and Chet Noyes moved Sierra Machine Co. from San Pablo Avenue to 733 Dwight Way at Fourth Street in Berkeley, near the Aquatic Park (but before there was an Aquatic Park), San Francisco Bay, and the Cutter Laboratories (later famous for manufacturing polio vaccine). Next door to the new location (733 & 734, in the same building; they tore down the wall between) was the Reliable Manufacturing Co. Owned by Albert G. Larson, it was a machine shop that had been there (at 734 Dwight Way) since at least 1927 featuring “air compressors, stampings, tool and die work.”

Harry had invented, designed and built a unique compact washing machine that fit into laundry trays, those double-deep cast-iron sinks that used to be in most garages, basements, or laundry areas. In those days regular washing machines were huge and expensive. Many people didn’t have room for them. Harry’s invention fit over the center bar of the two sinks. The wash was dropped into the first sink, where it was swished mechanically with hot water and soap. After that was done, the wash was lifted out by hand, fed through the rollers of a motor-driven wringer, and allowed to fall into the fresh rinse water in the second sink. Harry apparently bought Reliable Manufacturing Co. to manufacture his compact washing machines. Now he owned two manufacturing companies side by side, with shared offices, though Sierra was the more important of the two. In about 1934 Sierra became a headquarters for Fairbanks, Morse & Co.

By the 1930s America was in the midst of the Great Depression and everyone was looking for extra income. For this reason, Harry started gold mining. He had long been interested in the gold country and he finally found an area where the water conditions and “the color” were to his liking. In about 1935 he and a friend, Fred Hoyer leased some land near Cottonwood on the South Fork of Cottonwood Creek near the Sacramento River, about 15 miles south of Redding in northern California. Nonie recalls that Harry and Fred were the only two working partners in the operation; there may have been other owners, but she wasn’t aware of any.

At least part of the funding for the project consisted of a loan from Hazle Shurtleff. The men built a large gold dredge that worked on the river, bought a $25,000 bucket and shovel, and went into the gold mining business. This was a very exciting and profitable project. (Don Lawton thinks it was temporarily profitable, but then just slowed down and trickled out.) In March 1936 Helen Lawton wrote:

Birney Seymour is going to take his two boys up to Redding for the weekend. He is going to work some gold mines (hydraulic). Harry Peet and four other men bought some gold property. In 4 days they took out $2,000 on the regular land, which is the best land. All winter they worked the creek beds and got about $500 a week. They have about $50,000 invested, so they expect to do well when it is paid for.

Nonie recalls: “Harry and Fred Hoyer built the dredge and Fred operated it by himself. It was really a terrific operation to behold. Harry was seldom there unless there was a breakdown that he was needed to repair. We, or he, did make frequent trips to bring the gold down to the San Francisco mint.”

The operation continued full steam until World War II started, at which time the U.S. government stopped the mining and appropriated all the equipment. Big buckets and shovels and dredges were high-priority items. Lawton Shurtleff recalls that during the Depression, his mother, Hazle, used to say (at both Crocker Avenue and at The Ranch), that the one thing she could depend on was Harry’s monthly check paying the interest on his loan.

Harry spent roughly equal amounts of time working on the gold dredging and with Sierra Machine.

During the mid-1930s the Peets spent a large part of each summer at Monte Rio on the Russian River, together with the Martins and Seymours. In the early years they stayed at Frank and Fannie Lawton’s house, but after that they occasionally stayed with Winnie Seymour and in rented houses. The kids had great fun together and all became good swimmers under the tutelage of Pop Dean.

In 1938 the Peet family moved from Regent Street to 53 Tunnel Road, just two doors up the road from the entrance to the Claremont Hotel on the uphill side. Catherine Green Du Puy and Fred Du Puy lived next to the Peets at their new home.

The Peets moved to Tunnel Road primarily to get into the Berkeley School District (so Nonie and Mardy could go to Berkeley schools) but also because it was a better and bigger house. Mardy walked from there to Willard Junior High School.

When Nonie started high school, because her family lived in Oakland, she was not allowed to attend Berkeley High. So after graduating from Willard Jr. High in 1937, she spent her 10th year at University High School in Oakland, and really missed all her Berkeley friends. After moving to Tunnel Road, she enrolled in Berkeley High, but discovered that, due to her year at University High in Oakland, she was not going to have enough time to finish her college preparatory work in the remaining two years at Berkeley High. So when the Anna Head School opened two weeks later, she enrolled there. She walked to school each day and graduated after two years, in June 1940.

Roy and Hazle Shurtleff returned to California in the summer of 1938 and bought a ranch in the Alhambra Valley near Martinez. Harry and Dorothy Peet (and Don and Billie Lawton), who were very close to Roy and Hazle throughout their lives, spent many a weekend at the ranch, in part because they didn’t have second homes of their own, and they lived nearby. Harry (and Don Lawton) worked with Roy on a host of special projects: building bridges, dams, or dog kennels, hauling topsoil, planting gardens. Nonie and Mardy Peet, who had a love of dogs, spent quite a bit of time with Hazle, helping her with her dogs and kennels.

By about 1939 (after moving to Tunnel Road) Harry felt he had gone as far as he cared to go with the Sierra Machine Co. and the Reliable Manufacturing Co. Above all, he was tired of his partnership with Chet Noyes. At that time he sold his interest to Noyes and sort of retired for a while. But soon he was restless, in fact climbing the walls, looking for a company to occupy his creative energies.

Thorsen Tool Co., World War II, and Mardy’s Polio (1940-45). In about 1940 Harry located a small business called Thorsen Tool Company that looked interesting and promising. He probably learned about Thorsen through his membership in a local manufacturer’s association and his many friends in that small manufacturing community.

What money Harry had was largely invested in the gold mining operations and equipment, so he once again approached his brother-in-law, Roy Shurtleff, to ask if Roy would be interested in investing in Thorsen and willing to loan him $6,000 to help him buy the company from Sherm Haskins and his partners. Roy’s response came as a big surprise. Yes, he would be glad to put money into the business and help Harry buy it, but he would want his son, Lawton, to represent his interests and be Harry’s working partner. Roy knew Lawton and Bobbie were leaving Oregon to return to California.

Nonie recalls that, in part because of his experience with Noyes, Harry was reluctant to get involved in another partnership, especially with a relatively inexperienced young man who was also a member of the family. “There was a lot of discussion at home. Harry said, ‘No.’ Dorothy and Hazle told Harry that he could handle anybody, including Lawton, if anyone could. So Harry agreed to the arrangement. Soon Harry and Lawton developed a solid respect for one another.”

Lawton recalls: “From the day we started together installing an oil stove in the office until the day Harry retired, we had a wonderful working relationship—and there was never any doubt that Harry was the boss. He was an inspiration to me in my first real job.”

The group bought the company in December 1940 for about $22,000. Initially Harry owned 49 percent, Roy (a limited partner) owned 34 percent, and Lawton and Bobbie Shurtleff owned 17 percent.

Thorsen Tool Company had been founded in 1926 at 5325 Horton Street in Emeryville, California, by Sherm Haskins (production), E. A. Boyd (salesman), and Pete Mortensen (tool and die maker). They had all come to the area from P&C Tool Company in Milwaukee, Oregon. The factory in Emeryville was outfitted with used machines made during World War I. It manufactured a line of mechanics hand tools. By 1931 Boyd had split off and had started his own distribution company (named Thorsen Tools Inc. at 1475 Bush Street) in San Francisco. Pete Mortensen returned to his former company, P&C Tool Company in Oregon, leaving Sherm Haskins as the sole proprietor.

When Harry, Roy, and Lawton bought Thorsen in 1941 it was run down, virtually shut down, and losing money. The original 15 World War I vintage machines were still in place but many of them would hardly run. Sales were less than $3,000 a month and the value of broken tools returned for credit was about the same amount. There were five employees (not counting Harry and Lawton): Sherm Haskins, his brother Ed, Arturo “Toots” Bovo, a tool and die maker, and a grinderman. The main products were sockets, socket wrenches, socket attachments (extensions, flex handles, ratchets, speed handles), flat wrenches (box, combination, and double open end), and a wide variety of very specialized automotive tools.

One reason for the company’s poor sales and profits was that it had established exclusive relationships with four tiny distributors, each of which sold only about $500 of Thorsen tools a month: E. A. Boyd’s Thorsen Tools in San Francisco had exclusive rights for northern California; California Tool Co. had the rights for southern California, south of Bakersfield; General Tool Company controlled Washington and Oregon; and Old Forge in Pennsylvania had an exclusive for the East Coast. Moreover, and almost unbelievably, the Thorsen factory private branded the tools for three of the four distributors! As Lawton Shurtleff recalls, “Sometimes I’d set up the marking machine to stamp special brands on only six sockets—and I’d sometimes spoil two of those.”

Harry (who was 48 years old with two children) and Lawton (who was 27 with one child on the way) had different aspirations for the company. Harry wanted to keep Thorsen pretty much like it was but with more emphasis on job shop type special orders. He wanted to use it as his main source of income to support his family. Harry liked and wanted to expand on the mechanical, engineering, and skilled hand work side of Thorsen; he had less interest in mass production. Lawton, on the other hand, wanted to invest in new equipment in hopes of building Thorsen into a major national tool manufacturing company. Lawton’s first recommendation, which had Harry’s reluctant blessing, was to discontinue all the exclusive (but not legally binding) distribution arrangements and to stop private branding. The distributors were furious. But in the long run, the decision proved to be good for Thorsen.

The United States’ entry into World War II in late 1941 gave Thorsen a new lease on life and led the company inevitably and exclusively into hand tool production, for no raw materials would be issued for any other purpose. Lawton, to whom Harry had delegated sales responsibility, soon landed a lot of small government war contracts (they seemed big at the time) and one large contract for wrenches for Indian motorcycles. Production and sales grew relatively rapidly, although remaining small by any standard. After a few years, Harry and Lawton bought out Roy’s interest in Thorsen.

In March 1942, Lawton left to join the navy, and invited Jack Sayre, his good friend and Harvard Business School roommate, to replace him. Throughout the war, Harry managed and ran the company. Sayre reminded hardworking Peet a bit of Chet Noyes; fortunately Sayre left after one year to join the war effort. Then Harry invited Gene Shurtleff, Lawton’s younger brother who was working in the shipyards, to come in to help him with the administration. The other members of the informal management group were Dorothy Peet and Helen Hussey, Harry’s sister. Dick Eisenmeyer was office manager in the early days. Gene was there for about a year, from mid-1943 until mid-1944, when he entered the navy. Gene recalls:

While I was at Thorsen, we had three shifts, with 25-30 employees, working around the clock. We were selling over $12,000 of tools a month and profits were good. Each of us four “managers” would do a little bit of everything. Harry was very capable; he ran the crews and checked the quality. 1 did the payroll, paid the bills, bought steel and cleaned the toilets each Saturday morning. Helen Hussey was an absolutely delightful lady, with a great sense of humor and very capable. An awfully good worker, she used to sit out in the plant and pack tools all day long. Dorothy, too, worked like a man, rolling up her sleeves and doing whatever needed to be done. We each brought our own lunch box and ate lunch together each day in the office. We took this time also to discuss business matters such as scheduling, orders, payroll matters, and purchasing of supplies.

Business was very small but booming. In 1941, before the war, yearly sales were $40,000 and profits were $8,000 before salaries. By 1943 profits had grown 550 percent in two years, hitting a peak of $44,000. The next year sales peaked at $154,000 (profits were $41,000), up 385 percent in only three years.

While Lawton was away, he used his position as an officer in the Naval Supply Corps to visit a number of U.S. tool manufacturers and examine their machinery. He wrote many letters back to Thorsen, with suggestions on new equipment to buy and ways of procuring lucrative contracts. Lawton recalls:

At one point during the war while home on leave, I visited Thorsen and said to Harry, “1 really think we ought to buy a new-type sand blasting (tool cleaning) machine for Thorsen.” I had seen a good one at the plant of a Los Angeles competitor. It would improve our product and cut costs radically. Harry had more money invested than I did and he was not eager to put in more. I hoped to increase my share and I offered to pay for the new machine myself. Well, he took me out to the back lot and said, “Look. Don’t you ever make a suggestion like that to me again. We’re partners in this thing. If it’s good for one of us, it’s good for both of us, and visa versa. So when the time comes to make that decision, we’ll make it together.” I thought, “Boy, there’s a guy who stands on principle.” I was a bit chagrined at my offer. Except for that one minor incident, I can never recall another disagreement. I felt we had a wonderful relationship. He was quite a guy.

But there may have been good reasons for Harry’s reluctance in taking initiatives: First, Thorsen was working around the clock, keeping Harry on the run. Second, Thorsen’s first labor union was giving him new ulcers, and he had to start again to take his pink ulcer pills, which he called “Vaughn’s pills.” And third, a tragedy struck Harry’s family just when things at Thorsen were busiest, causing Dorothy to have to leave Thorsen. Nonie, Harry’s daughter and age 21 in 1943, responds to Lawton’s comments above:

Within three months of the war being declared, Lawton was no longer available to work at Thorsen. Although he stayed on full salary plus his participation in the profits during the war, he was no longer a “working partner.” His interest certainly continued but he was not in a position of being able to implement his ideas. It was not a time for “initiatives” to be taken. Without the highest priorities it was impossible to purchase bigger and better machinery. To get priorities you had to demonstrate that what you had was not usable. There was a war-time slogan for civilians: “Make it do, wear it out, use it up, or do without.” You couldn’t just place an order for new equipment any more than you could place an order for a car, a sewing machine, or a side of beef.

Frankly, Lawton’s advice was about as welcome as if he had come home to tell his wife that he could give her more dirty shirts to wash if she’s build a bigger wash board.

At Thorsen, they continually had to decline contracts for lack of space and manpower, and as it was, Harry even brought home buckets to be drilled on his tool room drill press. We all assembled universal sockets in the evenings at home. Dad went to work before the night shift left in the morning, worked all day, and then stayed on into the “swing” shift to get them started. He worked on weekends, too. I often went in with him to Thorsen so he wouldn’t have to drive in alone. It was a time for coping.

The real time for “initiatives” was after the war when the demand for good mechanics hand tools was at a peak. Lawton’s interest was certainly understandable for he had an active mind and there was lots of time in the navy for it to wander home. Thorsen’s increase in production during the war was miraculous—especially when the company began working three shifts, 24 hours a day as new orders came in.

Thorsen had great business opportunities after the war, with the greatest re-tooling boom the world has ever known.

In the summer of 1943, at the end of August, Dorothy and Harry’s youngest daughter, Mardy, came down with polio. It happened the same night that the Peets’ eldest daughter, Nonie, announced her engagement to Bern Kelly. The family was told by the best doctors that she would probably never walk again. But Dorothy and Mardy, heirs of the Lawton family determination and spirit, were not about to give up without a good battle. What followed is one of the most inspiring stories in the history of the Lawton family. It threw out a challenge that made everyone rise to their highest. Dorothy, especially, showed her true colors. Let Mardy tell us the story in her own words:

During the summer of 1943, between my low senior and high senior year at Berkeley High, there was a nationwide polio epidemic. I caught this infectious disease while working as a swimming counselor at a Christian Science summer camp. Nonie and her brand- new fiancee came to pick me up and I was feeling very sick. I was immediately taken by ambulance to the county hospital in Oakland and diagnosed as having polio. After a few weeks I was taken home to 53 Tunnel Road in an ambulance, just in time to see my sister, Nonie, go off in her wedding dress on September 11 to be married to Bernard Thomas Kelly in Berkeley. Needless to say the stress on Mother was immense.

When I arrived home I found that Mother and Dad, a hospital team, and many family friends had converted our dining room into a real hospital room, with two hospital beds (one for my nurse or physical therapist), and had a Sister Kenny setup in the kitchen. On a special sturdy table right next to the kitchen stove were two deep copper tubs. Atop one of them was a hand-cranked wringer. One tub of boiling water was placed on the kitchen stove. They had cut many large pieces of cloth out of heavy army blankets to fit around the different paralyzed parts of my body. First they would drop these heavy cloths into the tub of water until they were boiling. Then they would lift out these cloths with wooden hooks, run them through the wringer, and quickly bring these steaming “hot packs” over to wrap around my legs and other parts of my body. I was in a lot of pain. Mother and Dad and later Nonie and my attendants had to take turns; one person’s hands couldn’t stand the heat for very long. The Sister Kenny treatment, which consisted of continuous application of moist heat to the afflicted area, was then a fairly new treatment but was considered far more effective than any other known way of dealing with polio. Before that they used to splint the body to prevent bending as the muscles spasmed and contracted.

I was told I would he paralyzed for life. I would never walk again, and I would be very fortunate if I could ever sit in a wheelchair. Our first doctor had us all in tears describing how a totally paralyzed person might try to move around by hitching herself along. Doctors scoftill at the Sister Kenny treatment (probably because it had not been developed by a doctor) and told us we were probably wasting our time. But they had nothing better to offer. Doctors didn’t like polio and they didn’t like to care for its victims. But my mother, Dorothy, was willing to try anything that might work. The Sister Kenny treatment was our only hope. She had tremendous determination. When someone would express serious concern with my future she would say resolutely “We don’t need to talk about that.” It was one of her favorite expressions concerning negative situations.

For at least a year Dorothy was the person in charge of seeing that I was going to get back on my feet. In her mind that was going to happen. And she was not a religious person. (I was, always, and went alone to the Episcopal church). When dad came home from Thorsen at night, he’d relieve Dorothy. Both worked together.

I was in bed and someone was with me in the room for that entire time. Mom and a registered nurse took turns boiling the hot compresses, putting them through the wringer, then applying them to all parts of my body, from neck to ankles. They did this nonstop day and night, every hour on the hour, for the first one or two months. It was a big job each time those hot packs were changed, unwrapped and rewrapped segment by segment.

After that it was every waking hour, until I went to sleep. After six months of being flat on my back (so no muscles would be stretched), I was first able to sit up. The only time they would take one of the packs off was when the physiotherapist would work with me on specific exercises of one area to reeducate those muscles that were not totally destroyed. The process is mainly a mental one, using the mind to learn to make the muscles move. Mother was there all the time. I was almost never alone. She just wouldn’t give up. But gradually we realized it was working! The feeling began to return to my body. After six to eight months I was able to get into a wheelchair, and then after some months I was able to walk with a leg brace on my bad leg, no crutches.

Roy Shurtleff would bring me gifts when I was in bed. Hazle was always very supportive of me and always trying to get Dorothy out of the house so she could be something else besides a nurse. Billie would walk up the street with a special cake and play the piano for me so I could sing, which was also good for my lungs. Again the wonderful continued support from the many Lawton family members.

Don Lawton still remembers these years with clarity:

Mardy was in her senior year at Berkeley High School and about to graduate, but then she had to stay out for almost six months with polio. And by golly Berkeley High arranged to have her lessons brought to her frequently. On graduation night, after the school ceremonies were over, Elwin Le Tendre, who was the principal of the school, left the full auditorium, got in his automobile in the pouring down rain, drove up to the Peet house on Tunnel Road, and presented Mardy with her graduation diploma. Every time I think of it, tears come to my eyes.

Dorothy set her mind on this Sister Kenny treatment and nothing would change it. She said, we’re gonna go along with it and nothing would stop her! Boy! She had such determination and nothing would deter her.

By the spring of 1944 Mardy was able to move around a bit. At that time Hazle and Roy Shurtleff came to the rescue by inviting the entire Peet family plus Mardy’s physical therapist (five people in all) to come out to live at the ranch, primarily so that Mardy could use their pool for exercise and physical therapy. Nonie reflects: “It was a life-saving blessing and what an imposition. At the ranch there were no stairs to climb as there had been at Tunnel Road.” Initially the Peets all lived in the main house with Roy and Hazle. Then Hazle fixed up one of the many little houses at the ranch for the Peets to live in. Late in the summer of 1944 the Peets found and bought a house in Lafayette at 4105 Los Arabis Drive. They had chosen this site largely because it had room to put in a pool for Mardy. A pool was soon installed.

pool.

World War II ended in August 1945. In early 1946, as soon as Lawton Shurtleff returned to California, he met with Harry Peet (who still owned 81 percent interest in Thorsen Tool Company) and they had a long talk about the company’s future. The original major differences in aspirations for the company had not changed. But it was increasingly clear that they had to invest in new equipment and expand operations, or perish. Many of their competitors had rebuilt and financed essentially new factories out of their wartime contracts. As much as he would have liked to, Harry was unable to invest because of the financial needs of his family. Therefore he had understandably bought very little new equipment during the war. After this meeting Shurtleff wrote, “The company was mostly worn out and the abundant business opportunities offered by the war were largely unrealized.” After much deliberation, Shurtleff decided not to return to Thorsen.

He began to look for another company to buy into, if possible, first with Ernie Mendenhall, whom he knew from Blyth. Then he met Bob Ringle, from Cal Tech and Harvard Business School. Bob had experience in the tool business and he wanted to stay in it. He and Shurtleff discussed Thorsen. Three to five months after he decided to leave Thorsen, Shurtleff went with Ringle to talk with Harry Peet. As Lawton recalls:

Harry was sitting at his desk in the office. I said, “Harry, is there any way that you can think of that you’d be interested in selling your portion of the company if I could raise the money?” He reached into his pocket, threw the keys to the front door on the table, and said, “Lawton, if you can pay me what my interest is worth now, I want out.” Harry had made a good return on his original investment. There was no feeling of malice. He’d just had it. He was exhausted and frustrated. He was aware that the machinery was badly worn out, and was frequently breaking down.

So Bob Ringle and I bought out Harry’s majority interest. Some money that my mother, Hazle, left me in her will was of great help shortly after that. Fortunately Harry accepted our offer that he stay on to work with us. He stayed until 1952. His help was invaluable, as he was a fine mechanic and knew the mechanical end of the company. I have always felt that was an indication of our warm relationship. Sherm Haskins also stayed on until 1951.

As Nonie Peet Kelly recalls: “Lawton came back from the war older and wiser. He was dynamic, energetic, brilliant, and ready to put Thorsen into high gear. It was a fresh start and Harry was exhausted. Though he and Lawton were entirely different people, Harry was more than willing to go along and try new ideas. He was happy to let Lawton grab the reins and go for it.”

After two unsuccessful attempts at partnerships (with Bob Ringle and then Dick Warner), Lawton decided to go it alone. For the next eight years he struggled at subsistence level to meet each payroll payment and keep Thorsen afloat. The turning point came in 1954, when Carol Fortriede, a very successful salesman in the same field, joined Thorsen as sales manager. Together they made a fine team, in which Carol was the key to building a national sales organization. Together they launched the “new Thorsen.”

Nonie Peet Kelly remembers how “Harry was pleased as punch to watch Lawton make Thorsen into a smashing success.”

Memories of Harry and Dorothy. First let’s talk about Dorothy. Nonie Peet Kelly recalls: “Dorothy was fun loving, warm, and ready for anything. She had many jokes and funny stories but she was not a stand-up comedian and she didn’t tell jokes. I used to ask her riddles as a small child: ‘How is an ice cream cone like a race horse?’ Her answer: ‘The faster you lick it, the faster it goes!’ She always had a good answer or a totally irrelevant one that was funny at the time. We had some joke books around the house. One was called Puns and Conundrums, but it had riddles in it too. One of the riddles that I don’t remember the answer for had the answer ‘three green apples.’ When one of us asked her a ridiculous question, such as ‘When can I wear high-heeled shoes?’ or ‘Are we almost there yet?’ or ‘What will we have for dinner on Saturday?,’ if she didn’t want to answer or didn’t know the answer, she would reply, ‘The faster you lick it the faster it goes,’ or ‘Three green apples.” The funny stories she told were usually about such things as her encounter with nurses in hospitals (‘Shall we have a bath now?’ There’s not room in that basin for

both of us’), or about having to back up the Broadway hill to get the gas from the tank into the engine (there was no fuel pump or a weak one), or about getting lost. In other words, she took misadventures and made them pleasurable by the way she told the story. Like her brothers and sisters, she used humor to make hardships and problems enjoyable. Nancy Shurtleff Miller and Mardy Peet Love are both champions at this. Pure wit and humor—not comedy.”

Carol Lawton Pedersen: “Dorothy’s sense of humor was typical of the Lawton sense of humor. When she’d be serving cake, she’d say to me, ‘Would you like some cake?’ And I’d say, ‘Only a sliver.’ Then she’d say, ‘Any special place?!!”

Bimelyn Seymour Piper: “Dorothy was a real clown, so funny, so much fun, and always kidding a lot. She was totally wrapped up in her family and children, and she showed her dedication when Mardy got polio. If anyone in the family needed any kind of help, she was right there to do it, as when my father, Birney Seymour, was dying. She would help you even before you had to ask. And she was fiercely loyal to the family, as her mother, Fannie Lawton, had taught her to be.”

Gene Shurtleff: “Dorothy had a very quick wit and a great sense of humor. Even when things were at their bleakest, she always had a twinkle in her eye, and could crack a joke and get a laugh. She had a saying for almost everything. I remember her as a very lovable person, too. When our parents, Hazle and Roy, were away, Dorothy would often come to take care of us at Crocker Avenue. I remember at Thorsen she was a very hardworking person. She would work all day and into the night, just like a man, always willing to do more than her share of any hard work. She was capable of stepping in and doing anything that had to be done. Maybe the best example was her dedication to Mardy. That was her first major challenge in life, and she stepped up to it admirably.”

Don Lawton: “Dorothy was very clever and funny and joking, always with some little quips or jokes, just like our mother, and having a lot of fun out of it. She had a dry sense of humor and always found something to laugh about. She was smart and very sharp. Marrying Harry was one of the best things she ever did. Dorothy was just herself. She didn’t care to have anyone tell her what to do or how to do it. She lived the way she wanted to. She was a very independent person, quite like Harry. An all around nice person.”

Mardy Peet Love: “Like others in the Lawton family, Dorothy believed that you don’t share your health problems with the world and you don’t dwell on the negative aspects of life. If she had known that we were writing about her dear sister Hazle’s health problems, she would have stomped in here saying ‘This is not to be published. We don’t discuss those things.’ This goes back to the Christian Science influence in her upbringing.

“Though she definitely did not practice Christian Science, she’d often say ‘We’re driving a Christian Science car. Where there is a need, it will be filled. Don’t doubt. Let negative thoughts go.’ It pervaded all our lives. If she needed to find a parking place (as she often did after I got polio) she would just drive up to where she wanted to be. It worked.

“Mom had a superb memory. She liked to watch quiz shows and usually knew all the answers. She could also recite all her grandchildren’s birthdays. She was not intellectually lacking, but neither was she a scholar. She also had a rare sense of humor: a little cutting, dry, and sarcastic.

“Like her mother and sisters, she was a Good Samaritan, always looking for someone to help or take in. We always had different people living with us. Dirk Strickward, a Dutch boy attending Cal, needed a place to stay. Dorothy said, ‘Just send him to us until he finds a place.’ Two years later he was still there” (about 1945-50).

Now let’s hear some remembrances of Harry. Don Lawton: “Harry was one of the finest fellows I’ve ever known in my life. I just loved him. A gifted mechanic, he was a two-fisted man, afraid of nothing, a good, strong, husky, fearless person.”

Mardy Peet Love: “Harry and Don were very similar. They liked things mechanical, standing up straight, with a positive attitude, a nice smile, and not an ounce of fat on either one of them. Everything was always ‘just fine.’ They were lifelong friends. Harry always solved problems with a smile. If something blew up, it was just ‘Ah me.’ He had a wonderful disposition. He never said anything unkind about anyone, and he never raised his voice to anyone. He was unbelievably gentle and kind. Harry was almost ridiculous in the way he almost worshipped my mother. He felt that she was just the most wonderful thing in the world and he could never do enough for her.

She might demand it but …”

Lawton Shurtleff: “Harry was always an upbeat and optimistic guy. I never saw him when he was down or discouraged. He had great patience and was very easy to get along with. I don’t think I ever heard him swear in anger, though after work he liked to say, ‘We didn’t accomplish much today, but we’ll give her hell tomorrow.’

“Nothing ever looked like a problem to Harry, just a challenge to be overcome. He never saw a problem he couldn’t resolve. For example, one morning we arrived at Thorsen and there had been a flood. There was six inches of water covering the entire factory floor. I said, ‘Oh my God, what are we going to do?’ But Harry said, ‘We’ll have this factory running again in a couple of hours. Don’t even worry about it!’ This same sort of thing happened over and over again. What a wonderful way to look at life. Harry was always an inspiration to me. He was one of the most influential people in my life.

“He was a man of principle and great integrity. After the war, I hired our first black worker at Thorsen, Tom Brown. One of our key men, ‘Toots’ Bovo, who had been with us for many years, came to me and said, ‘Either you get rid of Tom Brown or I’m quitting. I’m not working with blacks.’ Harry, who happened to be standing there, said, ‘Well, how long will it take you to get your clothes changed and pick up your check?’ What a super guy! Bovo came back about 15 years later, said he no longer had a problem working with blacks (which may have been in the majority at Thorsen by that time), and stayed with us until I sold Thorsen to Hydrometals in about 1970.

“Harry was very thrifty. To some extent he was a product of the Depression in his outlook on spending money on business. When we’d drive to work in his car and had to stop to get gas, I remember how he’d often put in only a dollar’s worth. Nothing more than was needed.”

Nonie Peet Kelly: “Of all the people I have ever known, my father was the easiest to get along with. He was always flexible and would go the extra mile to do it your way. He was very much a family man and had interests far beyond his work. It was never his goal to be rich, but to enjoy what he had. His family and friends were his riches.”

Gene Shurtleff: “Harry and Dot were never very wealthy, but they were always very happy because they knew how to live without a lot of stuff. At Thorsen, Harry was much the same as at home. He treated all of the employees like family. He never lost his temper and was always kind and thoughtful. Harry was respected by all of the men in the plant and they were always willing to put out extra work. Of course Harry was the hardest working one of all. Really a good boss.”

Barbara Love Kremen: “My grandparents, Harry and Dorothy, were very warm and loving people, whose home was always a happy place. During the summer months, lots of friends and family were always swimming, sunning, and playing horseshoes. My grandparents helped my mom, Mardy, a lot; it was a wonderful extended family.”

Life in Lafayette (1944-65). As noted above, in 1944 the Peets moved to 4105 Los Arabis Drive in Lafayette. They put in a pool, mainly for Mardy. Built during the war from partly rationed materials, it was made of poured concrete with big oak wine vats housing the filter system. As Carol Lawton Pedersen remembers: “When swimming season began, the Peets would raise the flag, opening their pool and hearts to everyone. Pools were scarce in those days, so it was enjoyed by all. The Peets even sent out cards to certain young people saying “Membership in Peets’ Pool.”

Harry was a good horseshoe player. Lawton Shurtleff remembers many a good summer weekend match, with Harry throwing double ringers at the horseshoe pit by the pool. Then there were rubber inner tube races in the pool, badminton, and lots of pool-side fun.

In 1946 Mardy entered college at Cal and joined the Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority. She was able to walk without a brace for years. She notes: “It was mother’s courage and persistence that I have to thank for being able to get back on my feet.”

Mardy graduated from Cal in 1950, and on 20 April 1952 she married William De Loss Love, Jr., at St. Clement’s church in Berkeley. Many of the Peets’ neighbors attended the wedding. After the reception, Mardy and Bill arrived home to be greeted by an ambulance, the police and fire departments, and the coroner. During the wedding a small boy from the neighborhood had climbed over the fence (he and his brother were hunting frogs) and drowned in the Peets’ pool. Now both Nonie’s and Mardy’s marriage ceremonies had tragedies associated with them. The wedding turned into a wake. As Nonie reflects: “The whole family stayed up all night. It was one of the black days of the world.”

Dorothy had always been very close to her elder sister, Hazle. But during the last years of her life, Hazle’s physical and emotional health were not good. In late 1945 she and Roy were separated. Roy left the ranch to live alone in San Francisco. During the next few years Dorothy spent a great deal of time with Hazle, first at the ranch and later in Orinda, where Hazle died in May 1948 of lymphatic leukemia. Roy was extremely grateful to Dorothy for her efforts to help Hazle through her final illness. On more than one occasion he tried to give her a check for $10,000 as a token of his gratitude. But Dorothy never forgave Roy for what she perceived as his abandoning his wife in her time of greatest need. Several people recall that she told Roy, “You can take this money and you can do with it what you like. Nobody is paying me for the job that you should have been doing!” Dorothy called them like she saw them, and she stuck to her guns. She returned the check to Roy several times. So Roy left the money to Dorothy in his will, along with an expression of his appreciation. But Dorothy predeceased him, so Roy changed his will to benefit Nonie and Mardy. He was obviously grateful to Dorothy.

In 1952 Harry retired from Thorsen. For a while he puttered around home, working in the garden and helping Mardy to recover. He tried selling real estate in Lafayette for a while, but he was not very interested in that. After Mardy and Bill Love were married in April 1952, he went to work for Bill at American Molding Co., making plastic goods. But it was not the kind of work that he enjoyed, so he left. In 1953 he finally retired for good. Nonie remembers that “Harry loved his retirement. He and Dorothy used to baby sit, travel, and get-together often with their numerous friends and the family around them. They kept close to Don and Billie Lawton, and in regular contact with Winnie Lawton Seymour, Dorothy’s eldest sister.”

In about 1960, Harry and Dot took a trip in their car with Don and Billie Lawton to Los Angeles to visit Harry Lawton. On the way home, they took a little side trip to Yosemite. It was a big splurge since both couples were newly retired. Dorothy and Harry were both heavy smokers. Harry had smoked since he was young. Dorothy started the day her mother died. One of Don Lawton’s most vivid memories of the otherwise very enjoyable trip was sitting with Billie in the back seat of the smoke-filled car, hardly able to see out the tightly closed windows, while Harry and Dot smoked happily the whole way. Billie got a bit sick. Don reflects: “Smoking was the thing to do in those days. We didn’t realize it was bad for your health.” Both Harry and Dot stopped smoking simultaneously in 1975 when Dorothy was diagnosed as having emphysema.

Later Years at Rossmoor (1965-81). In 1965 Harry and Dorothy moved from Lafayette to a condominium at 2101 Pine Knoll Drive in Rossmoor, a retirement community in nearby Walnut Creek. Nonie recalls: “They enjoyed. That is, Harry enjoyed it more than Dorothy, though Katherine Green Du Puy, Dorothy’s lifelong friend, lived only about half a mile away. Harry loved every minute. He took up golf again, was elected several times to the Rossmoor governing boards, and generally had a ball. They added dominoes to their together and party games (bridge kind of slowed down) and Harry learned to love lawn bowling, where he also made a lot of new friends.” They were also a members of the “wet set” that swam regularly. Mardy Peet Love adds:

Harry had never been sick a day in his life. Then one day he just couldn’t get himself going, so we made him go in for a checkup. When the doctor asked him when he had last seen a doctor pr a checkup, he thought for a moment, then said, “1 guess when I was mustered out of the service after World War I, about 60 years ago.”

Harry was found to be suffering from chronic lymphocytic leukemia. He had a complete failure of his whole endocrine system and was sent to the Rossmoor Convalescent Home. Near the end, when doctors could do no more to make him well, he decided not to take any more medicines. One day, when I was with him, a nurse came into the room with some morphine. He was in terrible pain. She said, “Mr. Peet. how are you feeling?” He said, “Just fine thank you, how are you?” in his typical dignified and friendly way. I said, “Dad, you have to tell her you are feeling pain!” “Oh, all right,” he said. He maintained his manners and dignity to the end.

Dorothy could never discuss the fact with Harry that he was dying. It was impossible for her to do. I could, and share tears, but not mother.

One day, when Harry was nearly gone, weighing almost nothing, Don Lawton drove out to visit. In a voice full of enthusiasm, just as if nothing was wrong, he said, “Well Harry, let me tell you about what Cal did at the football game today…” It was pure soul to soul, just the two of them on a higher wave length, with Harry listening intently as if it were wonderful.

Nonie recalls: “Dad loved baseball. He made a super-human effort to live through the World Series that year. He just barely made it.” Nonie was the last person to see Harry before he died.

Harry passed away on 30 October 1977 at Rossmoor. Some years before, he and Dorothy had decided to donate their bodies to the Department of Anatomy, University of California Medical Center, San Francisco, for scientific research use. True to form, this was their practical, down-to-earth way of bowing out: Mardy notes: “They felt the body isn’t all that important. Neither of them was religious. It was for a good cause.” Nevertheless they decided to have their names inscribed on the Lawton family tombstone at Mountain View Cemetery, which they were. Mardy continues: