** All Text on these chapter pages has been copied verbatim – with permission – from this book: “Shurtleff Family Genealogy & History – Second Edition 2005” by William Roy Shurtleff & his dad, Lawton Lothrop Shurtleff ** Text in pdf convert to word doc – any spelling errors from the book may or may not have been fixed. **

Since you’ve asked me to tell you some stories about my life, I guess we might as well start at the beginning. As you know, I am in my nineties now, so if I pause from time to time to recall a detail or two, please bear with me. I remember most of it, though, as if it were yesterday. My dear wife, Billie, and I have had such a happy life together. Golly, I wish she could be here with us now.

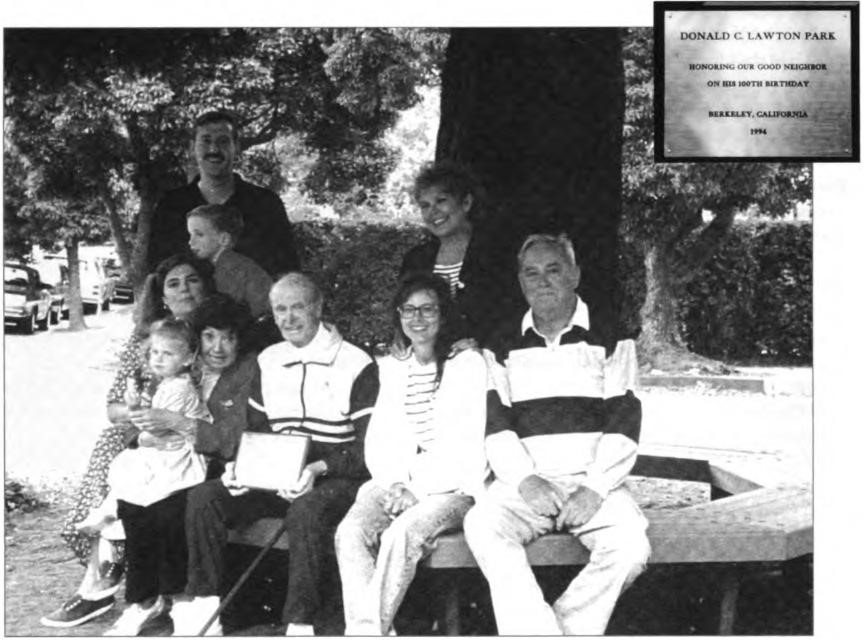

Growing up in Berkeley (1894-1910). I was born into the most wonderful family you can imagine. What a bunch! I was the sixth one, the next to youngest, arriving on August 2, 1894, born at our home in Berkeley at 2211 Durant Avenue I don’t know where my middle name came from.

As a small boy I loved to build things. I liked tinkering, fixing things, anything mechanical. When I was just old enough to hold a hammer, about seven or eight, we started to make skate coasters to ride on Durant Avenue, from Telegraph down to Shattuck. First, we’d nail the front part of a skate to the bottom front of a three-foot-long two-by-four board, and the back part of the skate to the back. Up on the front we’d nail an apple box, with a broomstick on top for a handle, and away we’d go. Since the street was rough, with crushed rock and oil, and full of potholes, we’d race down the sidewalks. But here and there on the sidewalks there were open gutters and cracks, so I nailed laths over every opening on the sidewalk on our side of the street for 300 yards, so we wouldn’t catch a wheel. We had more coasters than you could shake a stick at. They all had brakes, some that rubbed against the wheels and some that were drag brakes, held up off the sidewalk by a spring. Our family and the Witters we loved those skate coasters just like today they ride skate boards. But that was 85 years ago, when we made our own!

We also had roller skates. Once I tried to skate backward all the way down Durant Avenue to Shattuck as fast as I could go. I took a bad fall.

When I was 10 or 11 years old, I was the mascot for the local fire department, which was only one block away. There were only two firemen (Charlie and Archie) and they had two horses. Every Saturday morning I would rush down to the firehouse and polish the brass on the fire wagon, which they called a “hose wagon.” It got its water and pressure from city fire hydrants. After that, they would hook up the horses and exercise them by racing them with the wagon up and down Durant Avenue. I had the privilege of riding on the back platform every Saturday morning. That was my job. I’d wave to my friends as I’d go by.

Of course I couldn’t ride with them to real fires. But I kept a pair of overalls alongside my bed and a pair of rubber boots and a shirt. As soon as I heard the fire bells ring, I’d jump out of bed, put on my outfit, and grab my tricycle, which I kept in the basement. Putting one foot on the rear stand, I’d push with my other foot and rush either to the firehouse or straight to the fire. I’d go to every fire in Berkeley, to watch the fire.

In those days I used to run errands for Mrs. Bly, who lived two doors from us, just beyond the Solinskys on Durant. One Christmas Mrs. Bly took me to the toy department of the Emporium and said I could pick out any toy I wanted in the entire store. So I chose a big varnished hook and ladder fire wagon, about eight feet long. It had two seats, one behind the other, three ladders, and yellow wheels. It cost $10 and it was delivered by horse and wagon. Then the next Christmas, when I was about 10, my parents bought me a billy goat from our dentist, Dr. Hutton. Judge Waiste gave me an old streetcar bell that we could ring with a rope from the back seat. We kids had the billy goat pull us all over Berkeley.

When I was in about the second grade at McKinley grammar school, my teacher hit me on the knuckles one day with an oak ruler, probably for acting up in class. The next day, after my mother, Fannie, found out why my knuckles were so red, she went marching into that teacher’s room at school and said, “Nobody hits my children! I’m taking him out of this school.” So I went to a grammar school in lower Berkeley where the curriculum was easier. But when I went back to McKinley a year later, I had to repeat the year I had missed.

I remember when I was about 12, at McKinley Grammar School, I got my first job. It was at Max Zobel’s drugstore. I got the job because I had found an old bicycle under a house on Fulton Street, left by the Arthur Bells when they moved. It had no tires, just the wooden rims, a seat, and handlebars. So I went to mother and asked her for some money to buy some tires. She said, “Well, what are you gonna do with it?” And I said, “Well, I’m gonna ride it.” She said, “I don’t see any sense in that. All you’d do is sit and wear your shoes and the seat of your pants out, while getting no place. If you had a job, that would be different. Then there’d be a reason for buying tires.”

So the next morning, I went to every drugstore in North Berkeley and I finally wound up on Bancroft and Telegraph at Max Zobel’s. I said, “Do you want a young man to deliver goods after school and on Saturdays and Sundays?” He said, “As a matter of fact we do. We can use you.” So I rushed right down with my $5 and bought two cloth tires; I had more punctures than anybody in Berkeley. I went to work for Max Zobel delivering prescriptions.

Judge Waiste, the superior court judge in Oakland who lived across the street from us on Durant, was a friend of Admiral Dewey’s. He was a very important man, a friend of almost everybody’s. One day, after I had been working at Zobel’s for about six months, he asked mother to come to dinner on board Admiral Dewey’s flag ship in his White Fleet that had just come in to San Francisco Bay. Mother told me that we were all going to go meet Admiral Dewey as a family. I told her that Zobel probably wouldn’t let me off. But she said firmly, “If he won’t let you go, you’ll just have to quit. You’re going with us.” But when I asked Zobel he said, “Well young man, you have a job here. We can’t let you off. We need you. If you can’t come to work, you’re fired.” I said, “No I’m not. I just quit!” So we all went over to the fleet and had a great dinner on board the admiral’s ship.

I’m not sure when I first got interested in cars. But when I was about 12 or 13, in grammar school, Barney Olfield was the great automobile racing guy. He used to race these stripped-down cars with no fenders on Foothill Boulevard in Oakland and Hayward. That was the beginning of racing cars. Anyway, my friends Clay Sorrick, Shelby Vollmer, and I made duplicates of those cars out of wood. We called them automobile coasters. They were like soap box derby coasters, with no fenders or motors, but with good drag brakes. We had the time of our lives racing each other. We’d start at Telegraph Avenue and coast down Durant Avenue all the way to Shattuck.

In Berkeley, we had what was known as Idora Park, down on Telegraph Avenue, halfway to Oakland. I used to walk down to that park, jump the fence, and either ride the Ferris wheel or the Scenic Railway, or go through the coal mine. The Scenic Railway [a roller coaster] was so high you could see all over the town. The coal mine was a railway in a tunnel built like a coal mine. Each ride cost five cents.

In about 1908, when I was 14, I got the idea that I’d like to have a Ferris wheel like the one in Idora Park. So I went around to the houses being built in Berkeley at the time. At night, after the carpenters had left, I would find short pieces of two by four that I knew they wouldn’t want and I built a Ferris wheel in sections in my basement, then assembled it in our backyard. My father had a big, high swing that went up to the second story, about 18 feet. I used the swing support posts to hold the Ferris wheel in place. It had four wooden seats. The cross bars were all made of shovel handles that I knew the PG&E fellows didn’t want. I’d take a shovel now and a shovel then. The axle was a great big piece of three-inch pipe. We had a lot of fun riding that thing, till the seats broke out, then we’d just ride hanging on to the cross bars, spinning round and round like a monkey in a wheel. We’d spin so fast that once in a while we’d fall off and hit our heads on the concrete below. One fellow, Gervin Waite, who was the daredevil, would stand up on our high platform, get the thing spinning by pushing it with his foot, then just jump into the wheel hoping to catch one of those bars as it came whirling around. Well, every once in a while he’d miss the bar. It would hit him on the head and he’d get knocked down and out. So we’d douse him with water and wet towels, and after he came to, he’d get right back up and do it again. He later became port captain of San Francisco and Seattle harbors. He became quite a guy.

When I was about 14 or 15, we had our home in Monte Rio. I decided I’d like to ride my bike to Monte Rio. My bicycle tire had a big hole in it. So I went to our dentist and got a big chunk of rubber, the kind they used to put it in your mouth when filling your teeth. Then I bound up the tire with rubber, glue, and tape, put a rawhide boot over it, and laced it with rawhide shoe strings. No gears. I went to San Francisco on the ferry, landing at the Ferry Building at the foot of Market Street. I took another ferry to Sausalito. Then I biked to Santa Rosa, but on a long upgrade my legs cramped. So I stayed in a hotel at the top of the grade, and the kind man only charged me 50 cents, including breakfast. The next morning I coasted into Guemeville, and rode on to Monte Rio, where I stayed for three or four days in our family home. Then I went to visit Winn, who was teaching at a little one-room country public school way out in the hills, outside of Petaluma on the King Ranch. There, I went out quail hunting with a bunch of fellows. When they shot the quail, I went out and found ’em in the bush. I didn’t know I was out in thick poison oak. I had to pedal my bike all the way back in the hot sun. When I got home Mother said I looked awful and told me to go take a nice hot bath. Well I did, and I stayed in the bath tub for a week. The cure in those days was for me to stand in the bath tub while they threw cold water then raw salt on me, to “burn” the poison oak out. I missed a week of school. It was awful. I was just covered with the stuff.

My best friend since I was about eight years old was Howard McCreary. I also used to take some long trips with him in his car. In 1910 we took a 400-mile trip to his ranch south of Fresno.

In our late grammar school and early high school days, Shelby Vollmer and I would borrow a tandem bike from a son of Dr. Hutton [the dentist] and ride it out to Orinda. We’d go swimming in Orinda Creek near the Orinda train station by the Orinda crossroads. Also my chum, Howard McCreary and his two next door neighbors, the Schuler Brothers, and I would take his old horse, Maud, and rent a wagon from Charley Cane, the blacksmith. We’d get up at 4 o’clock in the morning and go over the Old Fish Ranch Road, then over to Orinda, turn right, and go out to Alamo and Danville. We’d swim all day in the creek and slide down the muddy sides, and just have a big time. Then wed get home about twelve or one o’clock in the morning.

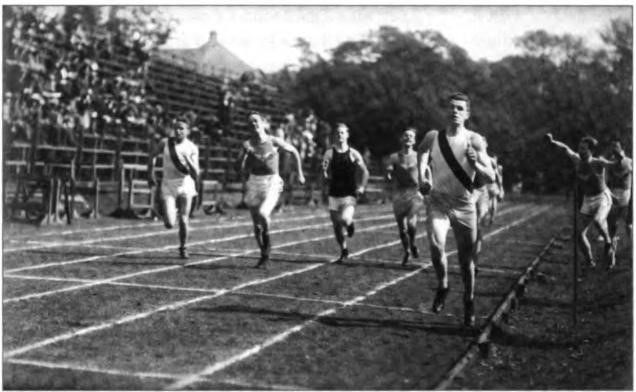

Berkeley High School (1911-14). I started high school at Berkeley High at the start of 1911, as a sophomore. We had only three years of high school in those days. My big things in high school were motorcycles and automobiles, plus sports, especially track.

I first got interested in motors in about 1910 when I used to hang around with Burt Bettis, who had his shop in the base of this big windmill near Berkeley High at the end of Bancroft Way. The windmill was used to pump water out of the ground up into a big tank that supplied his house with water. Burt Bettis was an unusually clever mechanic, who used to repair all of the motorcycles for the Berkeley Police Department. I’d watch him and little by little I just kind of caught on and soon I was doing some of the work myself. I used to work nights taking motorcycles apart. One day at his shop in about 1911-12 I learned about a fellow who had an Indian motorcycle for sale. The engine was all apart and put in this tomato box. All I could see was two tires and a frame, no peddles at all. So I bought it for $5, brought it home and by golly there I had a project. I put it all together, painted it, and got it running, then put on running boards for my feet. Not long after that, in 1913, I traded it for an old used Duck motorcycle down in Oakland. I fixed it up in our basement, had it for a while, then sold it for $75.

The first automobile I ever got was a little two-cylinder, chain-drive Ford. It was an old antique, made in about 1900, an old piece of junk. The no-skid tires were studded with steel caps. I got it in Alameda for $25 when I was a sophomore at Berkeley High. I drove it home, took it all apart, then went to Rolland Martin’s (See Chapter 29) garage and used his hydraulic press to put a new Woodruff Key in the flywheel on the crankshaft. I fixed it all up.

A year or two later, while I was still at Berkeley High, I got my second car, another Ford, through an ad in the Berkeley Daily Gazette. It was a hand-crank, Model-T Ford touring car, a nice running little car. I bought it in Berkeley for $250 that I had earned from cutting lawns. It was my pride and joy, and I had more fun with that thing. I had it for a year or so, then finally sold it when I was in college.

I was telling you about windmills. Well, in about 1906-07 when I was about 12 years old, we had hundreds of windmills pumping water all over Berkeley. You’ve probably seen a windmill, but how about a dogwheel? There was one windmill just a block away from us on Bancroft, and indoors, in its base there was a big dogwheel, about 8 to 10 feet in diameter. It was owned by old man Welcher. I used to go over there with Clay Ristenpart, who lived right next to Welcher. The wheel was geared to pump water, based on dog-power; no dogs, no water. It was the damdest thing. The longer and faster the dogs ran around inside the wheel (kind of like big white rats or hamsters), the more water got pumped. We used to sneak in there at night sometimes and run around in that dogwheel. One time we accidentally broke off a board in the wheel, so we ran home and hid in our basement before old Welcher could catch us. After that, whenever we ran in the wheel, we always had to step over the hole left by that broken board to keep from tripping.

During high school I was assistant stage carpenter for two years at the Bohemian Grove play. In April 1911 I was invited to join the Eunoia Club, a boys social group. My junior year [1913]1 was also elected to the school Board of Control and was the athletic editor for the 011a Pod ride, our school yearbook.

Elizabeth Witter was the one who got me interested in track. She said I could run faster than any kid around. I only ran track at Berkeley High my sophomore and junior years, 1912 and 1913, and I won my letter each year. My specialty was the 440, including a 440 lap on the mile relay team. Some thrills I remember were winning the 440 against Oakland High in the spring of 1912. I ran a 54.4 to beat Jakey Learner; he must have had a broken leg! Then in the spring of 1913 in the BCAL [Bay County Athletic League] I won the 440 again and placed in both Interscholastics.

That year I gave father a ticket to the California Interscholastic Track Meet, with schools from all over northern California. He went, and when we got home he said, “I enjoyed the meet, but that’s the last of track for you. It’s bad for your heart.” That was the only reason, though maybe he thought it was hard on my studies too. After track season my junior year I was elected captain of the track team for the next year. But I couldn’t run. Also, my parents took me out of Berkeley High and sent me to Jimmy White’s preparatory school for the first six months of my senior year, which was during track season. I liked the prof and I learned how to study. But after six months I said, “No more of that. I don’t like it up there! I’ve got plenty of make-up credits. I’m all set to go.” So my parents said okay, and I went back to Berkeley High for the last six months of my senior year. In those days there were two graduations each year. I graduated with my class in December 1914.

Athletic League 440-yard dash for

Berkeley High School, circa 1913.

I also swam on the swim team, the 50 yard, the 100, and the relay both those years. I was pretty strong in the arms so I got along all right. I swam double overhand (what they call freestyle today) with a weak flutter kick (swimmers used a scissors kick for distance). We wore swimsuits with straps over the shoulders. We’d play water polo also.

College at Cal (1915-18). I started Cal as a freshman in January 1915, at age 20. I entered at mid-year, joining the class of 1918. I had no thought of going out for freshman track because of father. I joined a fraternity, the Fiji house (Phi Gamma Delta) just like my older brother, Harry. Our big white house with columns in front was on Bancroft, right across from the old Cal football field. Well, the Fijis pushed me into going out for track, so I finally did. I ran the 440 and the relay on the freshman team. My teammate Gibbons was a great runner. When my parents asked what I was doing each day after school I’d say casually, “Just fooling around.” The final episode happened like this. I was running the 440 in one meet and winning. Some guy that filmed the newsreels for the movie houses stood right in my lane with his crank camera, and I had to jump aside not to hit him. Well that week, wouldn’t you know it, mother and father went down to the Orpheum Theater in Oakland. When the newsreel came on, mother yelled out, “There’s Don!” Father had never been so embarrassed in his life. When they got home father said firmly, “All right. That settles it. No more track.”

So I decided to go out for crew. Father said, “That’s fine as long as it doesn’t interfere with your dinner hour at 6:00 sharp, here at the table.” I found that the crew trained until 8:00 at night, so that was out too. Finally, my sophomore year, I went out for water polo.

I had started rowing way back in 1906 in Monte Rio on the Russian River. As a boy I spent much of my vacations rowing my own small boat from one end of the river to the other. Then in November 1915 I first started to row on San Francisco Bay. I bought this homemade canoe, sight unseen, for $3 from a fellow student at Berkeley High, Jimmy Bretherton. We got it out of his locker at Lake Merritt Boat House. It looked like it was made out of oil cloth and barrel staves, with no rear seat. Shelby Vollmer and I paddled to the end of the Oakland Estuary to the Mole. The canoe leaked like a sieve. By that time the canoe was about one-third full of water. Then we made a dash across the bay for Goat Island [now called Yerba Buena Island]. There was no Bay Bridge back in those days. After dumping the water out again, we paddled over to San Francisco, to where the World’s Fair [officially known as the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition] was being held. It was built on land made by filling in a shallow part of the bay with debris from the 1906 earthquake, on the spot where the marina and yacht club are now. The purpose of our trip was not to go to the fair but to test the soundness of the canoe. Arriving much later than planned at the fairgrounds, we quickly got a half-gallon grease bucket to bail the canoe, then headed back. Now it was getting dark and windy. The bay was very rough and it was necessary for my friend Shelby to sit on the bottom of the canoe and to bail out the badly leaking boat with our bucket. I paddled alone that night all the way back to Berkeley in the dark and enjoyed every minute of it. The waves got so high that Shelby was up to his waist in water as he bailed. We finally got to the Berkeley pier that Thanksgiving eve. The next day my friend, Howard McCreary, put that old canoe on top of his brand new Peerless automobile, and we brought it home. I repaired the leaks, built a new seat, and later sold it for $5!

During 1915 I visited the World’s Fair almost every Saturday. It was super, much bigger and better than the one later held on Treasure Island in 1939-41. The thing I remember most was the assembly line that Henry Ford built to make Fords right before our eyes, from start to finish, on the fairgrounds. I also visited the domed Palace of Fine Arts.

I still loved cars, but I had sold the two Fords I bought and worked on in high school. One day when I was a sophomore at Cal and tired of studying some damned econ book, I walked all the way to Oakland to about 20th and Broadway to Hayden’s Auto Wrecker. Well, up drove this 1909 Buick and stopped right in front of the wrecker. It was a 2-cylinder model with chain drive, no front doors of course, a big high back with tufted red leather and buttons all over, and a big squeeze ball horn on the side. It had no windshield and was side cranking. You cranked the engine from the side rather than the front. It had this great big leather top with straps out onto the polished brass headlights, which were all acetylene gas, you see. You could push a button on the floor, and the whole steering wheel and column would flip up and you could walk right through the front compartment. It was the dame-dest thing. It was just beautiful.

I walked up and said to the guy, “Are you gonna sell this car?” He said, “Well, yeah. You wanna buy it?” And I said, ”Well, how much are you asking for it.” And he said, “Well, all I can get. I imagine around a couple of hundred.” I said, “Well, you go in and ask the wrecker what he’ll give you for it, and we’ll talk when you come out.”

I had my hat and coat and necktie on, but as soon as that guy was out of sight, I got right down on my back on Broadway there and scooted under that car. Every nut and bolt looked like it had never been touched by a wrench. It was a beauty. When he came back out, he told me the wrecker would only give him $20 for it. So I said, “Well that’s all it’s worth!” He said, “I couldn’t sell it for that.” We talked a while then I said, “By the way, where do you live?” He said, “Out in Richmond.” Well I said, “That’s our answer right there. I live halfway to Richmond, out in Berkeley. I’ll drive you up and put you on the streetcar right on my corner to get you home. Otherwise you’d have a terrible time getting clear out to Richmond from here.”

He said, “Where’s your money?” I didn’t have a penny on me. On the way home I had him detour up a steep curving hill, which that Buick climbed with ease. When we got home, Mother asked me, “How do you know it’s his car? He may have stolen it and the bill of sale too.” Only after I had verified everything for certain would she let me buy it. I paid him the $20, drove him down to the corner, put him on the streetcar, and said, “Good day.” That’s how I got started in the automobile business. I was a natural! I had more fun with that car all through in college, taking it to dances and everything. A few years later when I went to war, I sold it for $100. Well, my time’s worth something, isn’t it?

In my junior year I decided to go out for the Cal boxing team. I had learned to box mainly during my high school years in our backyard on Durant Avenue. We’d invite the neighborhood kids in and we boxed a lot. My older brother Harry was an excellent boxer, and he gave me many pointers. Harry encouraged me to go out for boxing at Cal for self-protection. But he warned me: “Don’t ever pick a fight. You never know how good the other fellow may be. You’re just taking a wild chance. Many a man has been knocked senseless because he picked on the wrong guy.”

There were only two heavyweights on the Cal team: Walt Gordon and me. Gordon was a great all-around athlete and the team’s star, a 220-pound black man, who almost turned professional he was so good. I weighed in at only 170. In 1916 the Cal team was invited go down to Stanford for a boxing match, the first ever between the two schools. Those were the fledgling days of intercollegiate boxing. On the morning of the tryouts, unbeknownst to me until 25 years later, Ray Lyman Wilbur, the president of Stanford, telephoned Benjamin Ide Wheeler, the president of Cal, and told him point blank, with no apologies, that no black man would be allowed to compete on the Stanford campus. And if they sent their black boxer, the match would be canceled.

On the day of the tryouts, I didn’t even show up, so sure was I that Walt Gordon would be the Cal heavyweight representative. Besides, I didn’t want to get pounded just to find out what we all already knew. So instead of going to the tryouts, I decided to stay home and work on my motorcycle. When I finished, I decided to go up to the old Harmon gym to find out how the tryouts went. Little did I expect what was about to happen.

When coach Kleeburger, the head of the gym, saw me coming, he told me to get my boxing trunks on quickly. There would be a match. I thought that was a bit crazy, but I went a couple of rounds with Walt Gordon. Then he hit me so hard in the jaw that it knocked me against the wall and all the wooden dumbbells fell down on top of me on the floor. Kleeburger said, “That’s fine, Lawton. You’re all right. Let’s have one more round.” I shuddered, but went ahead. And at the end of it, Kleeburger walked over and said to me, “Lawton, you go to Stanford!” I couldn’t believe it. It made no sense at all.

Coach Kleeburger decided that I needed some work on developing my right guard. So he called me back to the gym the next day for some sparring practice with him. After I repeatedly failed to keep my right guard up, Kleeburger warned, “If you don’t keep it up this next time, I’m gonna hit you. You’re gonna get clobbered. This fellow you’re fighting down at Stanford is no amateur. He is a real all-American.” So we took our stance, then he let go and he hit me on the chin. I fell flat on the gym floor on the back of my head, and I saw all the stars that everyone has ever seen in the heavens above. I saw bananas and oranges and chairs and boats and kayaks and half moons and full moons and everything, whirling around. I don’t know how I ever came to, but when I went home I couldn’t open my mouth to get my food.

The next day, after a knockdown and a knock out, I was not exactly filled with confidence at the prospects of stepping into the arena with the man who was then the amateur heavyweight champion of southern California, and who later became the Pacific Coast amateur heavyweight champion. The match took place on April 20, 1916. Whatever apprehensions I may have had on my way down to Stanford were magnified when I saw my opponent, a man named Tom Carey. He looked like Smokey the Bear, only about eight feet tall. He was a giant. But as good fortune would have it, just before the match I received some free advice from a professional boxing coach, Mr. Friedman, the man who had set up the fight. He suggested to me: “Don, if you’re gonna get clobbered anyway, open your gloves up, bury your head in both gloves, lean forward, and bring your elbows into your stomach. Just hold on tight there and let him use you as a punching bag. Then when he gets really tired, it’s your chance. You let him have it.”

Well, the match between our two teams at the Cardinal gymnasium was all tied up at 11:30 that night when we finally came to the last fight, the heavyweight division between Tom Carey at 225 pounds and me at 170. From his lightning attack during round one, Carey looked like a sure winner. But I followed my game plan, staying protected. In the second round Carey hit me square in the nose with his first hard blow, breaking my nose. I had blood all down the front of me like a stuck pig. God! I was just a mess. They shoved cotton up my nose and said to go back in. So for the third and last round, I thought, well, by darned, my nose is busted now, I can’t get any worse. So I let go with everything I had. He was basically a three rounder, so big and heavy that he got tired easily after that. But I was wiry and still jumping around.

Editor’s note: This is how the sports section of the local newspapers later described the event:

It took Lawton a round and a half to size up Carey’s windmill tactics. After 2 rounds the big fellow began to weaken. Lawton jabbed the Stanford brownie on the nose so fast that Carey could not get in one of his swings. An extra round was ordered. And if the judges thought the affair was even at the end of the third, they should have given the bout to Lawton when the fourth was finished. Lawton did nothing but jab Carey on the nose so fast they could not be tallied. But in spite of this it was decided to give the boys a 4-minute rest and go for a fifth round. (This was later found to break the law, as the State amateur boxing rules permitted no more than 4 rounds). This time Lawton made no mistake. Carey was tired and Lawton repeated his effort of the first extra round. This time the judges saw it and awarded the decision to Lawton.

Well, they carried that big, heavy man away, one guy under each arm. That’s the last I saw of him. Someone later told me that for the rest of my life, I often used to say of super things: “It’s a knockout.”

The next year when Cal sent Walt Gordon down to Stanford, Carey refused to fight him, because Gordon was so good. This black man, Walt Gordon, we might note, went on to be both governor and supreme court justice of the Virgin Islands, and chairman of the California Adult Authority in the 1950s. Carey became a physician in Los Angeles.

I didn’t have a lot of outside activities at Cal, but I was head stage carpenter.

At the end of my junior year, I said, “By golly I am so fed up with this college deal, I think I’ll just take a leave of absence.” There was lots of talk of America going to war, and I wanted to get out into the world and do something. This wealthy bachelor from San Francisco named Courtney Ford, who I had met at the Bohemian Grove, asked me to promise him that I would come to see him when I graduated. At the Grove, the summer before my senior year he said, “I’ll get you a job any place you want in any automobile establishment. I know ’em all.” He’s the fellow who really got me started in the automobile business. So I thought, “I’ll try his proposition and see what it amounts to. Maybe I’d like to get into the automobile business right now rather than waiting till I graduate.” So I went over to visit him. He called up a Packard dealer in San Francisco and got me a job selling cars. I explained to my boss that my background had been mechanical and suggested that he allow me to go into the shop garage for a month or two and learn every nut and bolt on that automobile, so that nobody could argue me out of any part of that Packard car. He liked the idea, and in that way I got extensive training. I worked on Van Ness at California for about two months during 1917, before enlisting.

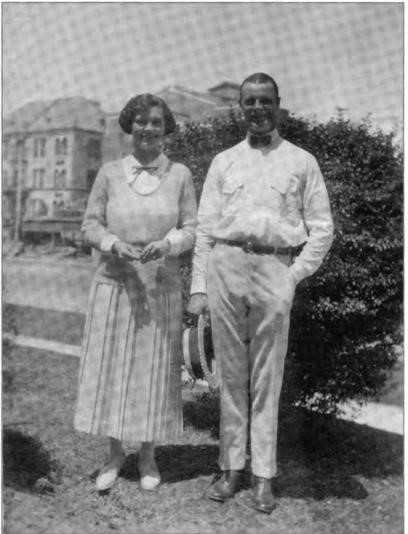

Image: Don Lawton, a volunteer sergeant in the Army Signal Corps, with younger sister, Dorothy, in front of father Lawton’s Durant Avenue house, circa 1919.

World War I (1918-20). When America entered the first World War, I first went down and enlisted in the truck department as a truck driver for overseas. Hearing nothing from them, I was convinced by a friend not long after that to enlist again, this time in the Army Air Corps. While waiting to be called, I got a job in the Alameda shipyards, as a timekeeper. I’d go along behind the head time keeper with a paint bucket. Every time he’d count a rivet I’d paint it out so they couldn’t count it a second time. Then I worked as an assembly man, and before I got through there I was foreman in charge of four assembly crews.

Next, I went up to Tacoma, Washington. They made me a sergeant in the Army right away because I had had two years of ROTC Army training at Cal, where I was a sergeant. I was sent to Camp Lewis in Washington and was now a sergeant in the Army Signal Corps, working to be a master signal electrician. I went to engineering school. Again my superior liked my skills. He made me a deal to live in officers quarters with a side entrance, and a twin Indian motorcycle with a side car and chauffeur at my beck and call. And a pass to anywhere in Texas, with the only stipulation that I report for work each Monday morning… for the duration. He called it “the best job in the army,” but I wanted to go overseas to work as a mechanic. Nevertheless the first half of the war I was stationed in San Antonio.

Then I was sent to France with the Army Air Corps 353rd aero squadron. I had earned the rank master electrical sergeant. When we arrived in France we found that all these black American stevedores were dating the French girls. When we asked the French girls what was happening, they told us that the black fellows had said they were the original American Indians.

I ended up at Camp de Souge outside of Bordeaux at the aviation department. I was a sergeant in charge of the machine shops, overhauling the engines. I also served as the physical fitness instructor each morning.

In November 1918 my brother Harry and I had met up in Bordeaux and had our pictures taken together. Then on April 10, 1919, two weeks after the war ended, we were given two weeks of vacation leave to visit all up and down the front lines in France. We traveled to Paris, Lille, Reims, Chateau-Thiery, and leper (Ypres).

When the armistice was signed, I was put in charge of dismantling our camp, which took four months. It pained me to have to sink brand-new Packard trucks in a mud lake rather than leave them in France, where they could be used by the French and therefore hurt car exports from America.

I was discharged from the military in August 1919 in San Diego. On the way home I stopped by, complete with dunnage bag and steel helmet, to visit my sister Hazle in Burlingame. Her son, Lawton, had just crushed his hand in a wringer and was Hazle ever grateful that it had been saved by Christian Science.

Selling Automobiles, Marriage to Billie Spaulding, and Starting a Family (1919-37). When I got home from the war, I went back to Cal and signed up, but found it too boring and uninteresting. So I never graduated from Cal. Just then my brother Harry was visiting after getting back from Newport News. He was visiting Roy Miller, who had the Dodge distributorship for northern California. As they were visiting this fellow came in from Colusa and said that he had just fired his shop foreman and urgently needed a new man. He asked Roy Miller if he could borrow a shop foreman, as he had urgent work to do. Harry recommended that I be given the job. I went to live in Colusa, which not far west of Grass Valley, working for the E. A. Boyd Dodge agency. There I was given full charge of the shop. That was my start of learning about the Dodge automobile, and I learned it up one side and down the other. After the first year everything was going great. They built us a new garage, the biggest building in town.

It was also in Colusa that I met my wife, Billie Spaulding. It happened like this. Billie’s formal name was Willie May Spaulding. She was born on January 7, 1897 in Colusa. Her father was William Caswell Spaulding, born 16 April 1872 in Colusa, the son of Alonzo Proctor Spaulding and Harriet Vegene “Hattie” Caswell. Her mother was Hattie May Simmons, born 22 November 1875, probably in Colusa, the daughter of Samuel Simmons and Agnes Sophia Becker. Her parents had both grown up in Colusa and were married on October 17, 1895 in Colusa. Billie had a younger sister, Ana Pearl Spaulding, born on August 7, 1899, in Colusa. Billie’s father, a blacksmith, died in Colusa on November 1, 1910, when Billie was only 13.

After Ana Pearl graduated from high school, she went to work in the post office. At the age of 22 or 23 she became ill with tuberculosis. Her dear friend, Ellis Crane, married her, knowing she was ill, so he could take care of her. About a year later, on September 13, 1926, she died of tuberculosis at the young age of 27. Billie’s mother was a darling person. She earned a living by working as a caterer for the Masons, the Masonic Order, and lived to the age of 85. She died on March 27, 1964 in Colusa.

Although there was not much money in the family, Billie was a determined person and she wanted to go to college. So she just made it happen. She was the only one in her family who went to college. In lifting herself up by her bootstraps, she took after her paternal grandmother, Hattie Caswell Spaulding. She had great talent in the field of music. Being able to sing and play the piano beautifully, she was able to get a music scholarship from Mills College in Oakland. A loan from a bank in Colusa provided the rest of the needed funds. She worked her way through Mills as assistant to the head of the music department, Madam Stuponi, teaching music, choir, and piano. Aurelia Reinhardt, who had been elected president of Mills College in April 1916, was making Mills into an innovative and exciting women’s college.

Nobody at Mills ever suspected that Billie was poor. In fact many thought she was a wealthy rancher’s daughter. She was a fantastic seamstress, and she made all her own clothes by lamplight at night. Throughout college and for the rest of her life, she was always exquisitely dressed up and groomed. Even when she just went down to the grocery store, she’d often be in white gloves. She said, “You never know who you’re going to meet down there.”

One of Billie’s best music students at Mills was Helen Boyle, from Coalinga, California. Helen, who almost went into grand opera singing, was married to Howard McCreary, who had been my best friend since we met in about 1906, in grammar school. We were buddies throughout high school and college. Now, when Helen heard I was going to Colusa, she got hold of Billie and said, “Oh my goodness sake, Don Lawton is up there. He is single and you look him up! I want you to meet him.” At the time, Billie was in Colusa, where she worked for 2 years teaching to pay off the loan that had allowed her to go to college.

Well, when I met Billie, I thought, brother, the world has been born. She was so dear and so strong and so forthright. When I look back it almost makes me cry. She was my God, morning, noon, and night. She was just so exceptional. I courted her on the big swing on the porch of her family’s home in Colusa.

She had a tremendous drive to do so many things. She was always learning as much as she could from everyone. She’d sort of pick their brains to find out. Hazle Lawton was very

instrumental in teaching Billie a lot of the social graces, etiquette, and the like. I was in love with this lovely, talented, popular young lady, and I admired everything about her. If she was going to do something, she would do it!

When I asked Billie if she’d like to settle down in Colusa, where I was doing well in the automobile business, she said: “I couldn’t get out of here fast enough. I hate this town. Please know, I would rather not live here.” Colusa was just a little town, and she wanted to make something of herself. But she had borrowed money from a bank in Colusa to help pay her way through college. I told her, “If we get married, I’ll take care of the money and all your past debts.” But she said, “No, I owe the bank, and I won’t be peaceful until I pay it off. Then well get married.” So Billie stayed in Colusa for 12 to 18 months teaching school to pay off her debts. She was the general superintendent of the Colusa County School District Music Department.

So I left my work in Colusa to look for a place where we could settle down together, near where I had grown up and Billie had gone to college. I went to Berkeley, where I started work at the Dodge agency on Durant and Shattuck, with two of my former Cal classmates, Ed Thomas and Bill Cottrell, selling cars. The day I arrived they welcomed me saying, “We’re waiting for you. Hang up your hat. We’ll split our commissions right down the middle.” I’ve been working with Dodges ever since.

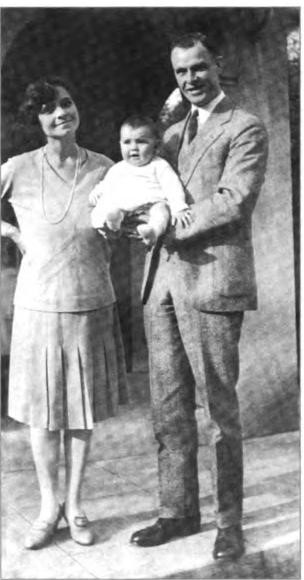

On July 6, 1922 Billie and I were married in Roy and Hazle Shurtleffs house at 372 Euclid Avenue in Oakland. Exactly fifty years later to the day, Roy Shurtleff remembered: ‘The bride, a lovely dark-eyed Mills College graduate from Colusa—the groom a serious six footer, who was accustomed to getting what he went after, and so got the girl. Lawton Shurtleff (age 7) and Gene Shurtleff (age 5) were ring bearers at the ceremony. Harry Lawton was the best man and Helen McCreary was the matron of honor.” After a honeymoon at the Highland Inn in Cannel, we moved very briefly into our first home together, a cottage on Stuart Street in Berkeley.

About three days after we returned from our honeymoon, Roy and Hazle Shurtleff said that an important friend was coming from Europe. They invited us over to meet Dave Babcock, manager of the Los Angeles branch of Blyth, Witter & Co. Babcock later wrote Roy saying, “Use every means possible to get Don Lawton to come to work in my office.” Though my real love was automobiles and mechanics, everyone told me a position with Blyth had more stature and future. They talked me into going down and looking it over. It was like a rush party. So we decided to try it, selling bonds. Billie had many friends in the Los Angeles Mills Club. Also our best friends, Howard and Helen McCreary, were down there. But the work didn’t really suit me.

In 1923, after about two years of working for Blyth in L.A., I got the flu and used this opportunity to go back to Berkeley. I went right back and got a job selling automobiles, first with Essex in Oakland for two days, but it had deteriorated from a swell car into the biggest pile of junk on the market. So I went back to my original place, the Dodge Brothers agency on Durant and Shattuck, which was now owned by the J. E. French Co. Who was there but Karl Goeppert, a friend that I used to run against in high school. He said, “Hang up your hat, we’ve got a job for you.”

On September 1, 1924 it was announced that all salesmen of the Bay District Dodge Brothers dealers who sold $100,000 worth of Dodge vehicles in the next ten months would win a free trip to the factory in Detroit, with a side trip to New York and the Great White Way thrown in for good measure. I immediately announced that I was going to be the one who would make that trip and went to work in earnest at our Berkeley store. On May 1 I called the J. E. French Co. to announce that I was the first to reach the goal. The two-week all-expenses-paid trip in mid-1925 was great fun.

In about 1927 Goeppert was made manager of our Grand Avenue Dodge Agency in Oakland, a big organization. Three days later he called me over and asked me to be sales manager of his 14 salesmen. I worked selling Dodges for 40 years.

When Billie and I moved back to Berkeley, we moved into a brand-new apartment on Hilgard Avenue just north of campus. We had to maneuver her piano up a narrow staircase onto the second floor. While we lived on Hilgard St., I got interested in chair balancing. First I was just horsing around, but pretty soon I got to the point where I could sit in a four-legged chair and just balance on the back legs, doing all of the balancing by merely raising and lowering my feet.

Before Christmas 1926, my sister Winnie asked me if I would build a 4-wheeled coaster for Birnelyn Seymour and her brothers. It had a chain steering wheel, a bell made from a danger on a brake drum, and running boards on the side. I built it in my father’s garage at my old work bench, and painted it bright red. They loved to ride it up and down the streets of Berkeley.

When we lived on Hilgard, our first child, Carol Mae Lawton, was born on March 5, 1927, in Oakland at Fabiola Hospital. In about 1929, we moved to a darling little cottage at 748 The Alameda, in North Berkeley. I moved in all the furniture while Billie was away, and surprised her. The Smiths lived next door and they soon became our dearest friends. Our second child, William Frank Lawton, was born on January 29, 1930, in Berkeley. I built a big swing in the back yard for the kids.

In about 1932 our family moved to 3315 Claremont Avenue in Berkeley, a wonderful, homey, happy house. We lived there for five years. One day I thought, “By golly, we enjoyed that Ferris wheel so much I built as a kid over on Durant Avenue, I’m going to build one for Carol and Bill, but out of steel.” Working in the basement of my father’s house on Durant Avenue, I built an 18-foot-diameter, all-steel Ferris wheel, suspended on great big self-aligning ball bearings and with four great big beautiful seats, plus lots of fancy steel work. I built it in sections, and Harry Peet did the welding for me at his refrigeration company in Oakland. The seats were all hand welded with curls and filigrees that made them look like real Ferris wheel seats. It took me nine months to build. It was hand powered. We’d put one kid in the lower seat, pull him up to the top, then put another kid of the same weight in the opposite seat, and pull them around. Every kid in the neighborhood just enjoyed that Ferris wheel no end. It was the talk of the town for years.

Soon the Ferris wheel idea expanded to become a park and playground in our backyard. Berkeley had its Lawtonland long before there was a Disneyland. We had an airplane you could ride in called the Good Ship Lollypop. It was a great big wine barrel with the sides cut down and leather seats and a wooden engine and full-sized propeller on the front with hack saw blades and bicycle sprockets. We’d spin the propeller and make it sound like a real engine. It was up on a six-foot pedestal made of an old truck rear end. It had wings, and a Hassler shock absorber inside, and a heavy chain going down through the bottom that would permit this big barrel to roll on this big brake drum and spin and dive just like a regular airplane. Screaming and yelling, the kids would ride the Good Ship Lollypop and hang by their knees going round on the Ferris wheel.

Then we had a rowing swing, on which four in a row would sit one behind the other and row just like you would in a boat. It would go quite high. In addition, we had a two-seater teeter-totter merry-go-round. It looked like a 12-foot-long teeter-totter but it spun around on a pivot in the middle like a merry-go-round. We also had a playhouse, with all the windows made from non-breakable glass out of old Dodge cars. Then we had an acting bar. I built each of these toys. When Carol was going to John Muir School, the teachers would march their students six blocks to our back Soon the Ferris wheel idea expanded to become a park and playground in our backyard. Berkeley had its Lawtonland long before there was a Disneyland. We had an airplane you could ride in called the Good Ship Lollypop. It was a great big wine barrel with the sides cut down and leather seats and a wooden engine and full-sized propeller on the front with hack saw blades and bicycle sprockets. We’d spin the propeller and make it sound like a real engine. It was up on a six-foot pedestal made of an old truck rear end. It had wings, and a Hassler shock absorber inside, and a heavy chain going down through the bottom that would permit this big barrel to roll on this big brake drum and spin and dive just like a regular airplane. Screaming and yelling, the kids would ride the Good Ship Lollypop and hang by their knees going round on the Ferris wheel.

Then we had a rowing swing, on which four in a row would sit one behind the other and row just like you would in a boat. It would go quite high. In addition, we had a two-seater teeter-totter merry-go-round. It looked like a 12-foot-long teeter-totter but it spun around on a pivot in the middle like a merry-go-round. We also had a playhouse, with all the windows made from non-breakable glass out of old Dodge cars. Then we had an acting bar. I built each of these toys. When Carol was going to John Muir School, the teachers would march their students six blocks to our back yard for an outing or to use our playground for an hour at recess time. Soon the whole grammar school, some high school, and even some college kids [through Lawton and Gene Shurtleff] were coming to play. It finally got to be too much. But we all had a lot of fun with it.

When we moved from that house I sold the whole thing to a man in Lafayette, but it never got reassembled.

In April 1936 Billie went to New York for a month’s visit as the guest of our close friends, my sister Hazle and her husband, Roy. It was her first taste of big city life on the East Coast and she saw enough plays to last most people a lifetime. She had a wonderful time and kept a detailed daily diary.

Early Years at Parkside Drive in Berkeley (1937-59). In 1937 our family moved into this beautiful big home at 35 Parkside Drive in Berkeley. We have lived here for the last 50 years. They asked $14,500 for it and we were able to pay cash.

Each evening as I drove home, Billie was there to meet me, all fixed up in a fresh dress, as she opened the garage door. Always immaculate, she just couldn’t be smarter looking. Billie always seemed to be busy, always bustling. In those years we got a household helper, Genevieve, who came every Monday for the next 40 years and also helped at dinner or cocktail parties. At those parties, Billie would play the piano and sing. Her favorite song was “My Sweet Little Alice Blue Gown.” She could just sing it like nobody ever sang it. My hallmarks were my private patented “knuckle knock,” a sort of flamenco rap that I’d let loose on our friends’ front doors to let them know we had arrived, and my warble whistle, used especially to announce breakfast.

We were always very close to Roy and Hazle, and their children. Being married to the next-to-youngest Lawton child, Billie was always Lawton Shurtleff’s confidante with Marty Haven, and later Bobbie Reinhardt. Lawton would bring his girlfriends over to our house. She was easy to be with, a matchmaker. When Roy and Hazle went back to New York, their son Gene was a favorite guest for dinner at our home. Billie always fixed his favorite weenies and sauerkraut.

In about 1936 I had purchased a 12-foot-long, double-ended rowboat, technically called a skiff, for $35 from the father of one of the employees at our Dodge agency. Called Hy Tyde, it was painted red and white, and sort of resembled a kayak (being pointed at both ends) but it had oars and outrigger oarlocks, which were located about a foot away from the side of the boat to give better leverage. I first used the boat on Lake Merritt. But by 1939 boating on San Francisco Bay had become my hobby, and each weekend found me rowing with the tide from the Berkeley Yacht Harbor over to the San Francisco Yacht Harbor or to Marin, then back to Berkeley. By 1940 I was getting bolder, rowing from Richmond or the San Francisco Yacht Harbor, out the Golden Gate, around Seal Rocks below the Cliff House, a real thrill, then back to where I started. This was my first foray out into the ocean in my tiny craft. I went out around Seal Rocks at least five times on different occasions. On one such occasion I narrowly missed being run over from the rear by a huge gray transport ship. I found this ocean rowing most interesting and at times exciting. For years I rowed to almost every point on the bay until this became quite routine and tame.

I was only shipwrecked once. During my vacation in early October 1946 [at age 52], I wanted to row up to Jenner at the mouth of the Russian River [about 65 miles one way] by way of the ocean, then on up the Russian River to Monte Rio, a new experience and by far the longest trip I had ever attempted. Billie took me over to the St. Francis Yacht Harbor in San Francisco at four o’clock in the morning. She returned home in the car and I set out in my 12-foot skiff for the Marin Coast. It was still dark as I rounded Point Bonita and saw the fishing fleet going out. The ocean started to get a little rough. Pretty soon I was hit by a strong north wind and high waves. Trying to row against that wind, I didn’t get to Bolinas till two in the afternoon. I had intended to be there at ten. I stayed the night in a hotel a ways back toward Stinson Beach. I talked to the Coast Guard and they told me how to proceed.

The next morning I left in my kayak-shaped row boat at six in the morning and rowed through Duxbury Reef. The north wind hitting those rocks and blowing the spray up made the reef look like a waterfall. The north wind was whipping up. It was just white foam all over the ocean. I couldn’t turn back. On the shore side the cliffs were 200 feet high for as far as I could see. There was no place to land and the wind was getting stronger. So I rowed until four in the afternoon, just breaking my neck; every wave would hit me in the back of the neck. I was under the water, then on top, then back under the water, up and down in the waves. By now the skiff deck and my body and bare arms were pure white with salt, except that some blood was coming out from under my armpits where the salt was piling up and digging in. I was trying to see if I couldn’t get some place to land. Then sure enough, there was a sand beach, just this side of Point Reyes. It was Drake’s Bay.

I decided to make a dash for it. As I neared the shoreline I unbuckled the rear hatch cover of my skiff so I could jump out. The wind grabbed it right out of my hands and tossed it into the air. It was later found a mile down the beach line. As I was about 25 to 50 feet from shore, with my back to the sea, I glanced behind me and saw a single whitecap comber, 10 feet high, racing toward me. Then the next thing I knew it had tossed me out of the boat and about 25 feet up in the air. Then I plunged down into the undertow. The boat was swooshed ashore, rolled over and over, and pretty well smashed up. I managed to get out of the undertow. I had learned how to handle myself in ocean currents during the early 1920s, when I worked for Blyth, Witter & Co. and swam each weekend with Dave Babcock in Santa Monica. Now, as I was knocked flat on my face on the ocean floor, I dug my hands in as I felt the current washing out against me. Then, still holding my breath, I crawled up this steep embankment under the ocean, through the seaweed and rocks. Dazed, I finally worked my way up on the beach where I could breathe. But I found I couldn’t stand up; the north wind was so strong it would knock me right back down on my knees. I stumbled and fell and crawled over to the boat. Then, holding onto a root, I drank some hot coffee from my thermos. I was chilled to the bone, so the coffee was a lifesaver.

I scrambled up the sides of a cliff and saw a deserted landscape, full of abandoned farmhouses and cattle skulls, but no sign of any people. Following tractor ruts, I walked for four hours until eight that night in the dark Bolinas forest. I stumbled along and heard wild animals. Finally I came across the San Rafael hunting lodge. When I asked to use the phone the lady there said, “Today? All the phone lines have been blown down. This is the worst storm we’ve had on the coast in 12 years. Trees have been uprooted. A posse has been out all day looking for a mountain lion that is in the forest killing our sheep.”

A car took me to a hotel in Olema. I phoned home to poor Billie who was worried sick and had been praying for me. Then I went to the bar and said, “Give me a double shot right now.” I had sand and salt in my shoes and hair, and seaweed hanging all over me. I looked like Robinson Crusoe. The guy next to me said, “My God, do I need a drink. I have just seen a mountain lion run across the road right in front of his car. It was as big as an elephant.”

The next day Billie drove me back to try to find my boat. There it was in Mrs. Compton’s backyard at Bear Valley Ranch. I said, “I’ve come for my boat.” She said, “Your boat? You abandoned your boat. It’s my property now!” I said. “Well, I’ve come prepared to buy it in exchange for all your work of getting it out of there. But I want that boat back.” She said, “Well, you can’t have it back!” I said, “Well, its too bad. It’s been my hobby and I’ve been shipwrecked. I’d like to put it back together again and make something out of it.” And she said, “Well, I’m sorry.” And I said, ‘Well, the only thing is, I’m gonna get it back and I’d like to get it back gracefully. If not I’ll have to go through the Coast Guard, of which I’m a member. I was thrown from the boat in this wreck; I didn’t abandon it.” She said, “Let me go in the house, I’ll be back in a few minutes.” She came back and said, “You can have your boat.” I said, “Well, that’s just wonderful.”

I went back to the car, where Billie was waiting quietly, furious that I was going through all this just to get back my own boat. I said, “Honey, you said just the right thing to Mrs. Compton.” She said, “But I didn’t say anything!” And I said, “That was the right thing!”

When I got home I sent Mrs. Compton two cases of wine in thanks. She apparently loved it, for she phoned the next day and said: “Mr. Lawton, I saw you out there in that storm through my binoculars. Standing on the high bluffs by the ocean, I saw you get tossed up in the air and go right down under the undertow. They don’t come out of that undertow. Many a person has drowned there, and I assumed the same thing happened to you. Later, scouting around, I found what I think is part of your boat a mile back toward Bolinas. It was on the bluffs about 100 feet up from the shore. Would you like it?”

I went back and got it. This time she was very nice. I spent the rest of my vacation rebuilding the boat. I put it all back together with brass screws this time and made it very seaworthy. But I assured Billie that I would never again go out in the ocean. That was it. But I did continue rowing on the bay.

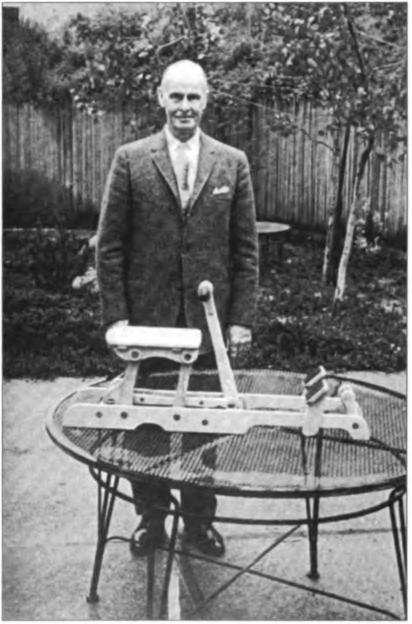

On one occasion in the mid-1950s, on a leisurely trip to Angel Island, I misgauged the tides, going out when the tide was against me through Raccoon Straights. Before I knew it, I was approaching Alcatraz Island. Suddenly the guards started to fire a hail of warning shots my way. I strained and groaned, rowing against the tide for more than an hour trying to get out of their range. I almost got washed out the Golden Gate. By the time I reached the lee side of Angel Island my arms were all cramped, knotted up and sore. That was when I decided I needed a regular daily training schedule. I couldn’t go out and row 25 to 35 miles a day, which I did, without being in good shape. So when I got home I started to develop a rowing machine, which later evolved into the Lawton Lift Exerciser. Now I was able to row every morning at home, never missing a day. Doing 200 to 250 strokes each morning, I soon got myself into top physical condition and developed strong endurance.

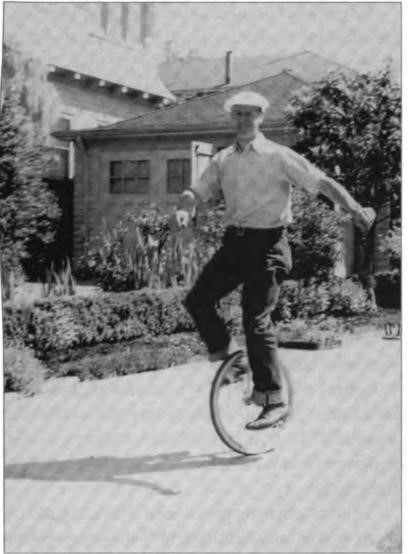

In those days I was always building something. So in the early 1940s I was thinking about a unicycle. It required a good sense of balance, which I had started to develop long before while balancing on chairs. There weren’t any unicycles around anymore. I remember seeing one on the Oakland Orpheum stage. This clown came in riding a bicycle, then he’d throw away the front wheel and handlebars and ride around on only one wheel. We thought that was wonderful. One wheel! That’s impossible. That’s where it started. I went to every bicycle store in town. Nobody had a unicycle, or even heard of it. Then I met a man at the Alameda Cyclery who used to be a unicycle rider. But when I told him I wanted to build one he said, “Oh my god, man, you see this scar across my head here, sewed up like a baseball? One day on a unicycle race for the Olympic Club, I smashed head first into a brick wall. My advice to you is stay away from unicycles. Don’t you ever get caught dead on one. They’re the most dangerous things in the world. But if you really want to get involved, I think there is a fellow out in San Leandro who has the unicycle that used to belong to a clown that used to ride it on the Oakland Orpheum Theater stage.” I went out and saw it, and it was a crude one. He wanted $7 for it. But I wasn’t going to pay $7 for that damned one wheel. So while he was on the phone I took the measurements and learned what I needed to build my own.

After I built my unicycle, I took more spills than you can imagine. I didn’t realize I should have learned holding onto a steel cable and a belt overhead. After I got so I could go around our block 12 times, I took off unicycling around Berkeley. It was hard work. Once I’d learned, I lost interest. Years later I used my old unicycle as the pumping agent in the pump I built for a 40-foot well next door. It’s still working.

Another contraption I developed in the early 1940s made it possible to have a steady gas fire flame burning in the fireplace without any logs. I simply took a piece of very strong vanadium steel pipe, capped both ends, drilled holes every few inches, and connected the middle to a natural gas pipe. Turn it on, light a match, and you have a cheery fire in no time, with no fuss. In fact, that’s what’s burning in the fireplace this evening.

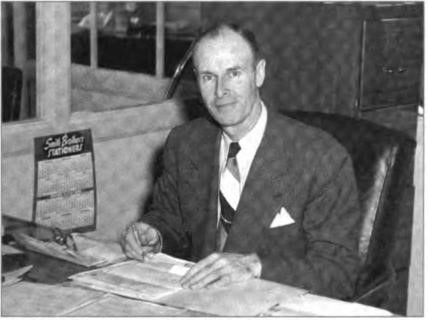

During the 1940s and 1950s I continued to work for the J. E. French Co. In 1950 I was promoted from sales manager of the Oakland store to general manager of the Berkeley Store on Dwight Way at Fulton. Just before retiring in 1960, I was told by Mr. French that of his four stores, Berkeley was the only one operating in the black.

Retirement and Later Years (1960-87). I retired from the J. E. French Co. in 1960. Now that I had more time, I started to work on improving my exercise or rowing machine. That

soon became my main hobby and also helped to keep me in good shape. In fact, I have maintained a daily training schedule at home for the past many years by using the Lawton Lift Exerciser. After I felt I had perfected the design [in the late 1960s] and applied for a patent, I began to get orders, first from friends, and then from their friends. I never advertised or asked anyone to buy them, though I did write a little four-page credo titled “I Believe in Exercise” in the mid-1970s. My motto was “Healthy Days Come in a Row.” Over the years I was increasingly swamped with orders. I probably sold 100 to 150 in all, and all over the United States. To make one took about two weeks. At one point I was a year behind in my orders. It got to be too much. I was trying to rush and push. Several companies, one in Sweden, one in Japan, one in Los Angeles, attempted to build them commercially, but every time the verdict came back the same: too complicated and too much hand work, because they were made out of white ash with nylon bushings and chrome plating. It involved a lot of detailed hand work which machines can’t do, and that runs the expense up. It was too confining. I was spending too much time in the workshop rather than out in the fresh air. I had too many other things to do. It was fun when I was developing it. I still get calls from all over.

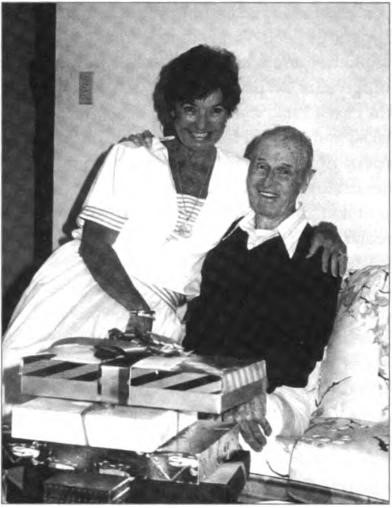

On July 6, 1972 Billie and I celebrated our Golden Wedding Anniversary. For fifty years we had fulfilled our vows to love and cherish one another. We can just be grateful for all these years of beautiful marriage bliss. We’ve had nothing but a wonderful life. If everyone could live the same way, I know the world would be a better place.

At the time of our anniversary Billie was starting to lose her vision, which was very difficult for her. So she requested that we not have a party. For that reason, Carol organized a 50th anniversary album. Our family and friends contributed 65 letters to commemorate the day. Editor’s note: The letters speak for themselves. Here are excerpts from just a few:

As far back as I can remember gaiety, humor, love, understanding, tolerance and devotion to each other, and to Bill and me, have been your pattern of everyday living… You two wonderful parents who have always placed the happiness of their children above all else.—Carol Lawton Pedersen

You both always seem so happy together and seem to love each other so very much.—Bill Lawton

Between the 17 short years that I have been alive, I’ve seen more love and mutual understanding between the two of you than between any two other people in the world… Daddy Don: You are the greatest, kindest, most caring, loving man I will ever know. You have become my model. When your time in this world has ended, your love and memory will be safe and alive with me -and I will pass it on.—Steven Gibson (Don’s grandson)

By the shining example of your life together, you have added glamour and lustre to the institution of marriage.—Jerry Martin

Of course, the Ferris wheel from those childhood days stands out so vividly in my memory as the most special toy in the whole world. Just another wonderful example of how much pleasure the two of you brought to all of us who have been fortunate to be a part of your great enthusiasm and zest for life. When I sit here now looking back on it all, it kind of brings a tear to my eye, as all I can recall about the two of you is a very, very loving, compatible couple, always so sweet and tender to each another from the time I can first remember you.—Nancy Shurtleff Miller

Who else has an aunt who sings like a bird, plays the piano like Liberate, cooks like Julia Child, and sews like Dior? And who doesn’t love to hear Uncle Don’s knuckle knock on the door signalling his arrival, that also means cheerful stories—jokes and puns are coming too. Congratulations on setting a fifty year example of what a really great marriage can be.—Nonie Peet Kelly

Daddy Don and Auntie Billie, to each new child in the area, the repairer of broken toys and distributor of cookies.

I love you for your grace as hosts, who make your guests feel like royalty. And conversely when you are guests you shine like jewels.

I love you for all the wonderful things you do for people who need morale boosters—the bedside calls, the delicious trays, or flowers, or notes.

I love you because you are yourselves: happy, handsome, well-groomed, a credit to the neighborhood, and a joy to behold.

Not without tears I must admit that without these two selfless angels I could not live alone in my house next door.—Ruth Atkinson

In 1982 I started a new project: making rocking horses that were big enough for my grandchildren to ride on. My daughter Carol’s husband, Arnie, showed me a pattern and the first one went to Barby Love that Christmas. Since then I have made about 10 of them. I guess I’ve always been a perfectionist about the things I build. And I rarely find a thing I can’t fix. Ed Martin used to say: “If a nail is one-sixteenth of an inch off, Don has to pull it out and put it back where it belongs.” I can’t stand to compromise where craftsmanship is concerned.

Well, now comes the sad part. During 1984 Billie began to lose her memory. Then in July 1984 it suddenly got worse. She got dysentery and couldn’t feed herself, and her memory began to disappear. She would leave the house, wander off, and be found three or four miles away, not knowing her name or where she lived. I was up all night for many nights trying to take care of her. One day Nancy Haven Stewart [sister of Mart Haven] dropped by, and when she saw the state Billie was in she said, “Don, Billie needs professional care. You can no longer take care of her at home.” I called Carol and Arnie at seven o’clock the next Saturday morning and asked for help. We took her to a convalescent hospital, where she was diagnosed as having Alzheimer’s disease. This silent, terrible thing is now the fourth leading fatal disease among adults in America. Of course, I visited Billie every day, but she had completely lost her memory. She’d be looking straight at me and didn’t even recognize me. It was pathetic. She now has a permanent catheter 24 hours a day, and it takes two nurses to move her around. Finally this year, Carol put her foot down. She said, “You’re not going down there so often.”

You know, I go down with a strong heart, but I’m just torn to pieces to see Billie sitting there with her once shining eyes so vacant, like a sack of sand. Till you have gone through it, you just can’t believe that there is so much nothingness to the whole thing. I mean there is just nobody there. Its rotten! When I first started to visit Billie, I’d come home and couldn’t eat. Everything tasted like sawdust. I lost 20 pounds. Still, when I come back I sometimes lose my voice for two or three days. I can’t even talk to a person. It just isn’t right, just the opposite of what it always used to be. Till the day she left, nothing could have been happier. Now it’s like a crazy dream, a nightmare. It doesn’t seem possible. We had the nicest, cleanest cut, most loving life together that anyone could ever have.

To pay for the rest home at $2,500 a month, we’ve had to set up a fund so that when our house is finally sold, it will pay all the past bills. I try to keep up my good health so that I won’t be too much of a worry to Carol for a long time to come, we hope.

During the past year I’ve been working on a chiropractor’s table and a cervical chair with a complex adjustable back for my granddaughter, Lauri, who is Bill Lawton’s daughter. I guess I’ve been building things all my life.

Sometimes people ask me if I have any secrets for keeping fit and healthy and young in spirit to age 92. I usually suggest a positive and cheery outlook on life, interesting projects to keep you busy, daily proper exercise, good food, and contentment in your home. Contentment means not to worry, stew, or fret. It blows your whole system out, then nothing works. A good diet might consist of grain at most meals (mush, toast, spaghetti, Spanish rice, macaroni), plain food, and very little meat.

I don’t have all the energy and vim and vigor I once did. It kind of reminds of a little poem I heard not long ago.

When I was young my shoes were red

And I could kick my shoes above my head.

As I grew older my shoes were blue

And I found there were quite a few things I couldn’t do.

Now that I am old my shoes are black.

And I just shuffle up to the corner and back.

And can’t wait to hit the sack.

Yes, I usually take a nap after lunch nowadays, but I’m still pretty young! I was up at about 5:30 this morning, as usual. I took a couple of glasses of hot water to start the day, did 100 strokes on my exerciser, then went right down to my workshop there. I’ve got so many things I want to build and so little time left that I sometimes feel I have to hurry. Tonight, as always, the last thing before I go to bed, at around 9:30 or 10, I’ll jump on my exercise machine, row another 100 strokes, and sleep like a doll! I still have 20-20 vision, don’t wear glasses, and can read the phone book without them. Your old Uncle Don still’s got plenty of the spirit that 1 had when I took on that guy Carey in the boxing ring down at Stanford 71 years ago. I’m not gonna go down easy.

Okay kids, off to bed. Thanks for listening to all my old stories. Please excuse me if it sometimes sounded like I was bragging, but you asked for it. See ya all tomorrow morning.

Editor’s Postscript:

In 1987, at age 92, Don was full of life and energy and spunk, hale and hearty, lean and trim, physically fit from head to toe, with remarkably good health, a clear mind, an almost unbelievably good memory, and a tremendous outlook on life, despite the undeniable pain and loneliness of his separation from his lifelong love and soul mate, Billie—who sadly died on 28 Oct. 1990 at age 93. The great happiness they found in each other continues to inspire those who know them.

Don was a master storyteller, far more than the printed word reveals. The stories told above are but a small number from his seemingly limitless repertoire. As his daughter Carol once said, “Daddy never tells the same story twice.”

Don and Billie had two children:

1. Carol Mae Lawton. Born on 5 March 1927 in Oakland, Carol graduated from John Muir Grammar School, Willard Junior High, Berkeley High School, then the University of California in 1948, majoring in English and philosophy. After graduation she attended secretarial school for 6 months, taking typing and shorthand. Her first job (Dec. 1948) was in San Francisco, with Shuman, Agnew & Co., a brokerage firm. She was an accomplished tennis player and she played throughout her life.

On 9 Aug. 1952 Carol and Maurice E. Gibson, Jr. were married in Berkeley at her parents home. Born on 28 Oct. 1925 in Oakland, he was the son of Maurice Embry Gibson, Sr. (an attorney), and Phoebe “Peggy” Wood. Maurice Jr. was an indus trial engineer. Carol worked as a secretary in the political science department at Cal for a year and then as secretary to Katherine Towle, dean of women. They moved to Ohio, where Maury worked as an industrial engineer for Universal Atlas Cement Co.

There, in Dayton, Carol and Maury had two children:

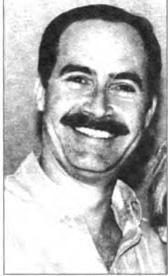

Steven Maury Gibson born 26 March 1955. He was a brilliant inventor in the field of computer peripherals. He invented the well-known Gibson Light Pen and Flicker Free, which takes the “snow” off computer screens. He lectured on computers and wrote articles for computer magazines, such as Info World. He is president of Gibson Research Corporation in Irvine, California, and perhaps is best known for his SpinRite software inventions. He is one of the foremost authorities on computer security. After 9/11 he worked briefly with Federal authorities on improving White House security.

Image: Steven Maury Gibson, son of Carol and Maury Gibson, and a gifted inventor, late 1970s.

Nancy Carol Gibson born 10 Feb. 1957. She married Kenneth Bradley Jochims on 16 Aug. 1980 in Hillsborough, California. He was born on 16 May 1957, the son of Alvin Jochims and Alma Krambeck. Both work for Apple Computer Co., Nancy heading up the Graphic Arts Department and Ken working as a computer engineer specializing in sales. Nancy currently has become a seam-stress par excellence, working at home as an independent contractor for a Design Group creating custom-made draperies, bedspreads, pillows, etc. She and Ken have two children both born at Stanford Hospital:

Evan Christopher Jochims born 25 April 1989, became an Eagle Scout at age of 15 and currently is a sophomore at Bellarmine College Prep in Santa Clara.

Jenna Catherine Jochim born 24 Jan. 1992 and attends St. Matthews Catholic School in San Mateo.

Image: The Jochims’ children, Jenna and Evan, at the Honey-moon cottage, Lake Tahoe, 2003.

Later in 1957 the family moved back to Berkeley. In October 1961 Carol and Maury were divorced in Martinez, California.

On 14 June 1963 Carol married James D. Glenn, Jr. This was an extremely happy marriage, but it ended tragically on 18 Aug. 1964, when he was killed by a train that hit his car at a crossing in Brentwood, California, a tiny town on a back road from Walnut Creek to Stockton.

On 19 May 1967 Carol married for a third time, to Arnold Richard Pedersen, in Berkeley. Born on 20 March 1923 in San Mateo, California, he was the son of Ewald Holm Pedersen and Sophie Hedwig Pedersen. Arnie and Carol lived in San Mateo, where he was the owner of Pedersen and Arnold Planing Mill.

In 1974 Carol decided to go back to work part-time. She worked as a legal secretary three days a week and loved every minute of it. When she wasn’t working, she and Arnie played tennis three or four times a week. She sewed, played the piano, and took cooking and painting lessons. She plans to purchase a word processor and work at home as an independent contractor typing “overload work” for attorneys, businessmen, etc., in San Mateo.

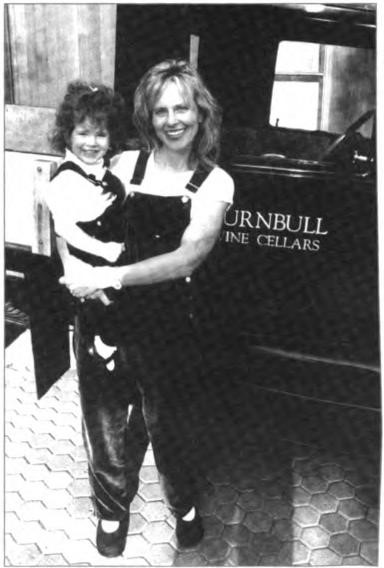

Image: Carol and husband Arnie Pedersen at Seadrift, Stinson Beach, California, circa 1988.

2. William Frank Lawton. Born on 29 Jan. 1930 in Berkeley, California, Bill graduated from John Muir Grammar School, Willard Junior High, and Berkeley High School. Bill excelled in athletics at Berkeley High, where he played catcher on the baseball team with feisty Billy Martin, who later became a baseball star and controversial manager of the New York Yankees and Oakland A’s. Bill also played football. His name was often in the headlines after the Friday afternoon games. In 1948, after graduation from Berkeley High, Bill was inducted into the army and sent for one year to Fort Lewis, Washington, where he served as a military policeman in the Second Division. Bill attended the University of the Pacific, graduating in 1954, with a major in labor economics and a minor in business. During his senior year, Bill’s roommate was George Moscone, future mayor of San Francisco, who was attending college on a basketball scholarship. After graduating from law school, George asked Bill to join his organization, but Bill declined. He worked those early years in the construction industry for Lawton Shurtleff and John Mackay.

On 20 June 1956 Bill married Sally Joy Saunders at the Piedmont Community Church in Piedmont, California. Born 10 Nov. 1934 in Oakland, California, she was the daughter of Charles George Saunders and Josephine Nunenmacher. They had two children:

Linda Toy Lawton was born on 17 July 1958 in San Jose, California. She works for a food brokerage firm in Redwood City, in the sales department. Currently Linda is a caregiver for the elderly, preparing meals, taking them shopping and generally caring for their daily needs.

Lauri Dayle Lawton was born on 26 Oct. 1960 in Oakland, California. She graduated in 1982 from Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo with a major in nutrition. After working in this field for 21/2 years, she decided to enroll in the Life School in Hayward, where she studied to be a chiropractor. In 1997 she married Christopher Camozzi. They were divorced in 1972. In 1996 she married Geoffrey Greitzer and on 21 Aug. 1997 had a daughter, Valentina. They divorced in 2004. In addition to her own business, Paradise Family and Sports Medicine Chiropractic, Lauri Greitzer has her own 20-acre ranch in Chico, California on which she buys, raises and trains horses.

Image: Sally and Bill Lawton’s daughter, Lauri, and her daughter, Valentina, circa 2000.