** All Text on these chapter pages has been copied verbatim – with permission – from this book: “Shurtleff Family Genealogy & History – Second Edition 2005” by William Roy Shurtleff & his dad, Lawton Lothrop Shurtleff ** Text in pdf convert to word doc – any spelling errors from the book may or may not have been fixed. **

Roy Shurtleff was born on 19 September 1887 in Nevada City, California. The birth was at the family home at 309 Gethsemane Street in the Piety Hill section of town. A photo, taken by Gene Shurtleff (his second child) in 1982, shows the ample, two-story house (see p. 62) to be sturdy and well kept. His name at birth was Roy Lathrop Shurtleff, but during his college years (before 1912) he changed the Lathrop to Lothrop, when he was told by the family genealogist, Benjamin Shurtleff, that Lothrop was the correct spelling. It was Roy’s grandfather’s first name and an old Shurtleff family name. Roy’s father, Samuel Shurtleff, born in Quebec, Canada, must have spoken French as his native language. Roy’s father and mother were both widowed. They were married on 6 December 1885, a little less than two years before Roy was born.

At the time of the marriage Samuel Shurtleff was 46 and Charlotte Avery Meek was 36 years old. Samuel had two daughters, Alice Maud Shurtleff (#1462 in the Descendants of William Shurtleff) and Mary Ruth Shurtleff (#1463), both living in Nevada City. Alice Maud, the oldest, married Mads Jensen Rohr (from Denmark) in Nevada City California, on 19 December 1895. They had two children there: Carl Samuel (born 19 January 1897 in Nevada City California) and Mary Ruth in 1899. Alice Maud died in Carmel, California, on 4 February 1952.

Mary Ruth Shurtleff, the next to oldest, married Henry C. Weisenberger in Nevada City, California, on 6 March 1889. They had one child there, Alice Maud, born 19 September 1890. These two sisters must have been fond of one another since each had a child named after the other.

Clara Lucia Shurtleff had died unmarried in Nevada City in February 1885, at age 17, shortly before her father had remarried.

Roy’s mother, Charlotte, had one son, Charlie Meek, and two daughters, Jessie and Nettie Meek. These became Roy’s half brother and half sisters, along with Alice Maud and Mary Ruth, his half sisters by Samuel Shurtleff’s first marriage. Thus when Roy was born in 1887 there were (not including Roy) three Shurtleffs and four Meeks living in the family home on Piety Hill, the best residential area of Nevada City. Roy was the youngest child by about seven years. Roy was born into a family that in 1887 looked like this, with ages shown at the time of his birth. Note that his mother, Charlotte, was age 37 at the time.

Samuel Matthew Shurtleff, Born 12 Aug. 1839, age 48.

- Alice Maud Shurtleff. Born 7 April 1865, age 22.

- Mary Ruth Shurtleff. Born 24 April 1866, age 21.

Charlotte Avery. Born 13 Dec. 1849, age 37.

- Charles Avann Meek. Born 5 April 1868, age 19.

- Jessie Meek. Born 25 Oct. 1870, age 17.

- Nettie Meek. Born 30 May 1880, age 7

- (Roy Shurtleff. Born 19 Sept. 1887)

Alice Maud Shurtleff would be married in eight years. Mary Ruth Shurtleff, age 21, would marry in two years. Charlie Meek was working in the drugstore his deceased father (John Meek) had owned in Grass Valley. Jessie Meek was Nettie’s older sister. Thus Nettie Meek, who lived at home, became the closest to Roy of all these children, in part because she was the closest in age, only about seven years older than Roy.

Roy’s father, Samuel, drove a stagecoach, carrying people from Nevada City to the town of Washington in California, off Highway 40. On 15 August 1890, when Roy was just a month less than three years old, Samuel was killed (at age 51) when his stagecoach overturned. So Charlotte Avery was once again left a widow, and her youngest child, Roy, grew up in Nevada City without a father. Eventually he would become the man of the family.

Nettie Meek recalls that after Samuel Shurtleff’s death, Charlotte’s income came from rent on the house she had lived in with John Meek in Grass Valley, from a store building in Grass Valley that she had bought with John Meek’s insurance money (it was the building in which the newspaper was published), and from dressmaking she did. The family may have received some financial support from Charlie’s work in the drugstore, but he soon went east to dental school, where he received his degree, supported by an uncle in Ohio.

Charlotte Avery Meek and Samuel Shurtleff had been married for less than five years, and Charlotte had come into a home owned and occupied by Matthew and his two daughters. After Matthew’s death, the Shurtleff girls began to view Charlotte as an unwanted stepmother, who had her own family—the three Meek children and Roy Shurtleff. They soon took over their Piety Hill home, forcing Charlotte, with Jessie, Nettie, and Roy, to move across town in Nevada City to a very small house in a much less desirable neighborhood. Roy later noted that his mother was so unhappy with the arrangement that she forbade him to see his half sisters, the Shurtleffs.

Nevertheless he did see them several times on the sly and they were always nice and friendly to him. Thus Roy, though a Shurtleff in name, never knew his own father and barely knew any other person named Shurtleff. Basically he was raised as a Meek, with his mother’s family, the Meeks. This may well explain his unusually deep interest later in life in the genealogy and history of the Shurtleff family. Roy later noted (1976): “I was raised by a frugal, religious, and loving mother who was ambitious for her children.”

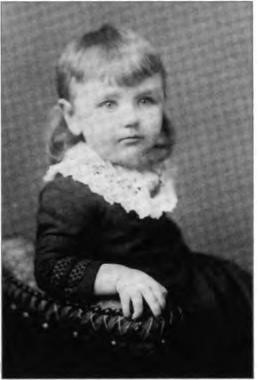

Another early photograph of Roy Shurtleff was taken in Nevada City when he was about two and a half years old. He had shoulder-length hair and wore a lace collar and a dress like that of a girl. His eyes and ears were already distinctive. The other earliest known photo of Roy dates from when he was about age five. It was taken with his half sister Nettie Meek, in front of a painted background in Grass Valley.

When Roy was a youngster, Nevada City was still a frontier community, an outgrowth of one of the mining camps of the early 1850s. The main industry was gold mining. As Roy recalled in 1941 in his son Lawton’s diary:

The town was the shipping point for the various mines within a radius of forty miles. A little, narrow gauge wood burning railroad connected Nevada City with the main line in Colfax. It wound its tenuous way between the two towns iwer spindly tressels and through long tunnels. The little engines with their-cone slumped smoke stacks were a constant wonder of power and speed to me; and it was a great priz’ilege and treat when mother would permit me to share in the excitement of meeting the evening train. Most of the town turned out if any notables were arriving.

Great freight wagons with trailers drawn by eight and ten horse teams picked up the mining machinery and supplies at the railroad and hauled them over the mountain roads to outlying mines and camps. They were picturesque and sturdy outfits with their lead horses equipped with bells erected from their collars. The bells rang loudly and merrily to warn traffic to turn off and wait.

Four and six horse stages also met the trains to convey passengers to the same mining camps and to bring back gold. Wells Fargo express guards with their protecting guns usually rode with the driver.

Our school was on the main road to the Yuba River Mines and the bells of the passing freighters often added direction to the day dreams of the drowsing classes. Then one day there was a stage robbery, with the express guard killed, and great was our excitement when the posse returned down the road past the school at recess time with the captured robber disarmed and tied to the horse.

When Roy started school in Nevada City, he had to walk one half to three quarters of a mile to get there.

In 1896, when Roy was about nine years old, his first publication and first poem appeared in the children’s column of the San Francisco Examiner under the title “A Nevada City Poet.”

Dear Editor-1 live in Nevada City. I am nine years old on Saturday. Mamma reads the children’s page to me. A mouse ate our musk melon seeds, so I wrote this poetry about it:

A FOOLISH LITTLE MOUSE

Once upon a time

A foolish little mouse

Came to my house

And ate our mushmelon seeds;

But in a trap

He put his head,

And it gave him such a rap

That he fell down dead.

We gave it to our old cat Dick

And he took it off quick

This is the last of the mouse

That came to our house.

Your friend, Roy L. Shurtleff

Nevada City, California

In 1896, when Roy was 10 years old, he was given an illustrated edition of Grimm’s Household Fairy Tales by his brother and sister-in-law, Charles and Minna Meek. Their handwritten inscription, “Merry Xmas to Roy, 1896, From Chas. & Minna,” still appears in the front of the book.

More than 50 years later, on Christmas in 1948, when he passed the book on to his eldest grandson, he reminisced:

I think I was alone a good deal as a young boy because my brothers and sisters were many years older than I. As a result, many hours were made happy by reading, and this was one of my favorite books. The book is old but the stories will be ever new down through the generations…

In 1897, when Nettie graduated from high school, Roy’s mother decided to move the fatherless family of three to Berkeley so that Nettie could get a college education at the University of California. Roy later recalled the day of their arrival:

The local steam train landed us at the little old wooden station at Shattuck Avenue and Center Street. There were no street cars, and if there were any cabs we couldn’t afford one. So we and our baggage rode in the old spring baggage wagon. The baggage man was an old Civil War veteran, with one eye, a dilapidated army cap, and a more dilapidated horse, which latter was hard put to make the grade up the winding and dusty road which is now Hearst Ave. Mother, through correspondence, had rented 2 or 3 rooms from a widow named Middlehauff. The house was on Ridge Road, above Euclid Avenue, near what is now Newman Hall. There were few houses there then, scattered through what had been an apple orchard. The apples made swell missives, and were highly regarded by the native children, of which I soon became one, as munitions both of offense and defense.

In 1898 Roy watched Americans go off to fight the short-lived Spanish-American War, in which the United States gained possession of Cuba and the Philippines. That year the family moved to its own little home, a one-and-a-half-story bungalow at 2128 Hearst Avenue near the corner of Oxford. Roy wrote his name and new address in the front of his Grimm’s fairy tales book. The family’s main source of income was probably Charlotte’s property in Grass Valley.

Just across the street was the home of Aurelia Henry (later Aurelia Henry Reinhardt, president of Mills College). Aurelia, born in 1877, was about 21 years old in 1898 and Roy (age 11) got to know her. The Reinhardt family would later (1939) join the Shurtleff family through marriage.

Roy, now age 10 or 11, started grammar school immediately at Whittier School in fourth grade, having finished grades first to third in Nevada City. He walked to school, which was quite a way west of Shattuck Avenue. The principal, Miss Keefer, he recalls, was a strong authority.

During his grammar school years Roy and a friend, Sam Stephens, had fun walking through the six-foot-high stone-walled conduit that channeled the flow of Strawberry Creek—the creek that runs down through the center of the Cal campus. Don Lawton recalled in 1987:

Strawberry Creek came out on Shattuck Avenue, then at Oxford Street it went underground. It went down under Allston Way to Shattuck Avenue, where it surfaced. The trains would go over it there on a trestle. Then it went underground on the other side of Shattuck, northwest toward El Cerrito, where it went into the San Francisco Bay. Roy would start at Oxford, near where he lived, and follow the underground creek all the way down to Shattuck Avenue (one long block), then he would come up into the open at Shattuck. Sometimes he would light candles to help him see.

The town of Berkeley had a population of about 20,000 at that time.

In 1898, Roy later recalled, the family had their first electric lights, which replaced oil lamps; the globes were not very effective and burned with a dull yellow glow—not much better than the oil lamps. The latter also had to be kept on hand as standby, because of the unreliability of the power supply. The family’s first telephone was installed in about 1900, yet it could only be used with the few other people who then had phones. Roy saw his first horseless carriage (automobile) in 1901-02. It was a little single-seated buggy with a steam engine in it, and white steam pouring out the back—probably an Oldsmobile or White Steamer. It chugged past their house, trying to climb dusty Le Conte Avenue, but couldn’t make it.

Most transport in those days was by foot (shank’s mare as Roy liked to call it), horse and buggy, streetcar, or train. In 1941 Roy wrote:

There was one street car line between Berkeley and Oakland. It ran from what is now Sather Gate to Broadway in Oakland. The Southern Pacific ran a local steam train which connected with the ferry boat at the Oakland Mole for San Francisco. It took over an hour from Berkeley to San Francisco and service was infrequent. The fare was, however, only ten cents, and free service was provided between stations in Berkeley. This latter led to one of the greatest sports of my youth, namely jumping on and off trains as they chugged up the Shattuck Avenue grade. The cops frequently chased us, because it was against the law, but that made it more enticing.

| Editor-in-Chief of 011a Podrida, the Berkeley High School Yearbook, December 1905. |

The Mole was the terminal by the Oakland Estuary where the steam trains connected with the ferryboats to San Francisco. Steam trains operated before the electric trains of the Key Route took their place.

Nettie graduated from Cal in the Class of 1901. She never married, but served as assistant to Dean Derleth at the College of Engineering through World War II. She was recognized as an important influence on the careers of many Cal graduates.

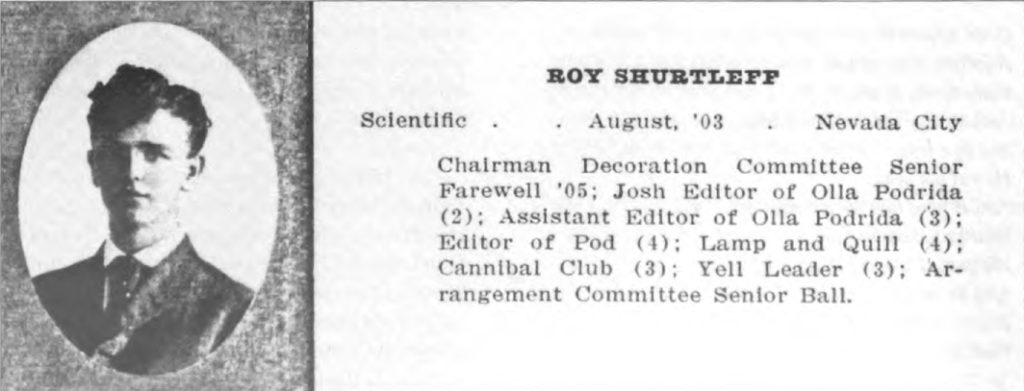

In August 1903 Roy entered high school at Berkeley High School, which had been founded in 1883. At age 16, he was quite old for a high school freshman. He worked hard at his studies for his first three years, but also participated in school activities.

In the 1 September 1905 issue of the Berkeley High School yearbook, the 011a Podrida (a Spanish term which means either “a highly seasoned Spanish stew” or “an unorganized mixture of diverse items, a potpourri”), published several times each year by juniors and seniors, we find Roy’s first published literary creations—a half page of Joshes, funny little poems about his fellow students.

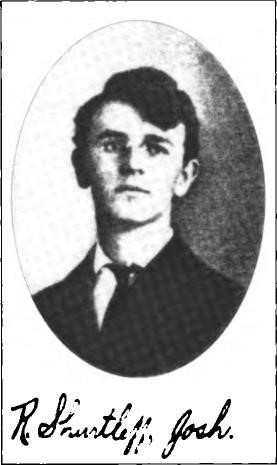

In the December 1905 issue of the high school paper we learn that Roy was active in school. Now a junior (Class of 19061/2), he won second prize in the high school poem contest, and his full-page poem “Looking Backward” was published. It is about a man who ruins his life by failing to work hard and to follow ideals set during his boyhood; instead he “followed pleasure’s beck’ning cry” and “shunned stern duty’s call.” Roy was the school’s elected “yell leader”—pretty brave for a boy with a serious problem stammering—and he wrote the Berkeley High yell, “Rouse ’em Berkeley High, Souse ’em Berkeley High…,” which was still used in the 1930s when his sons Lawton and Gene attended Piedmont High. His signed oval photograph appears on the page with the 011a Podrida journalism staff; he was the Josh (Humor Section) Editor.

In the March 1906 issue of the 011a Podrida, Roy wrote a humorous two-page short story titled “Billy De Buster Hits Berkeley.”

In the June 1906 Qua Podrida we read that Roy was a member of Lamp and Quill (the Senior Honor Society), a member of the Cannibal Club (founded in 1903; all members were guests at Roy’s home on Saturday, April 8), Associate Editor of the 011a Podrida, and the author of a three_ page humorous story titled “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” In the 011a Podrida of 24 August 1906 we find another story of Roy’s titled “A Trip to Heaven or How Eddie Soared: A Thrilling Novel in One Spasm.”

In the December 1906 issue of the 011a Podrida, the last published while he was at Berkeley High, we find Roy’s senior photograph. Next to it we learn of his activities: Scientific (not literary or social science). Year of entering Berkeley High: August 1903. Activities: Chairman Decoration Committee Senior Farewell ’05; Josh Editor of 011a Podrida (2); Assistant Editor of 011a Podrida (3); Editor-in-Chief of 011a Podrida (4); Lamp and Quill, (4) [Vice President], Cannibal Club (3); Yell Leader (3); Arrangement Committee Senior Ball.

Gene Shurtleff thinks that Roy also belonged to a school boy’s club named Eunoia — but he couldn’t have, because Eunoia was founded on 6 November 1910, several years after Roy graduated. Don Lawton, however, was in Eunoia.

Each summer during these years, starting when they still lived in Grass Valley, Roy and his mother and Nettie visited Roy’s grandmother (his mother’s mother, Maria Louise Avann) and Frank Reanier at their home in Capitola. They took the train from Grass Valley to Auburn, transferred to the train to San Francisco, then transferred again to the train to Santa Cruz and Capitola. Frank Reanier worked for the Hihn Company, which owned a resort in Capitola. Roy got his first sales job there. He was able to work on his stammering and to earn a little money on the beach selling “peanuts, popcorn, chewing gum, and chewing candy.” Any money he brought home from this work was matched by his grandmother in his savings account.

On 18 April 1906, Roy (now 19 years old) was awakened very early by a rumble and a roar. It was the great San Francisco earthquake. He went back to sleep, for their home was little affected. His high school, however, was pretty well demolished. Roy took a ferryboat to San Francisco and saw the conflagration and streams of refugees. Later in the week he returned to San Francisco in an effort to find his sister Jessie and her children, Roland and Herbert. Fortunately they were unharmed. Refugees poured over the ferries to Oakland and Berkeley, and these communities became sizable cities almost overnight.

At some time during his high school education, Roy dropped out of his regular school and went to a speech therapy school in San Francisco for one or two semesters. He had had a stammering problem since he was a little boy. It caused him more difficulty when he read aloud than when he spoke. It was more that the words wouldn’t come out, than an involuntary repetition of the same sound. Actually he liked to stand up and tell stories in front of his primary school class, and he was considered a pretty good storyteller. But his stammering got worse during the next few years. Roy recollected (in 1981 at age 94), that he had gone to speech therapy school during the seventh grade. However, Gene Shurtleff recalled (in 1984 at age 67) that Roy went to the speech therapy school in 1906, in place of his senior year at Berkeley High. Gradually Roy outgrew his stammering by learning to control it and speaking more slowly; by the time he reached college it was pretty well past, though it still caused him some problems when he was later selling bonds. He eventually went on to become a superb salesman and toastmaster. In a way, Roy’s speech problem may have aided his effectiveness as a speaker, since an audience tends to be more sympathetic to one whose speech is, at times, hesitating or unsure. But occasionally in later life, especially when he was nervous or tired, the problem would return.

To earn money, work on his stammering problem, and keep himself busy, Roy worked in Sills Brothers fruit store for a while during high school and on Saturdays drove a one-horse two-wheel butcher wagon for Samson’s Meat Market on Shattuck at Allston. Also (in about 1906) while on leave from high school, he worked for a newspaper called the Berkeley Independent, which had been started by Eugene R. Hallett. Roy did various types of work, including odd jobs around the print shop. Hallett, who was then a young man, about to graduate from the University of California at Berkeley, had been business manager of the Daily Californian, the university’s daily newspaper. The Blue and Gold of 1905 shows that Hallett was its Editor-in-Chief that year; he had a strong influence on Roy’s future. He felt that Roy had valuable talents and encouraged him to go on to college. So Roy returned to his high school and explained to the principal that he felt that he had done and learned enough to deserve a degree. The principal claimed not to remember him, but was willing to graduate him based simply on his word.

After high school and stammering school Roy felt it would help him to cure his speech problem if he trained himself by selling door to door. So he took a job traveling up and down the coast of California selling pots and pans. He later told Gene:

I remember calling on a lady one time. She listened to me give my whole sales pitch, then when I was all finished she said “I’m not going to buy any pots and pans but I just liked to hear you talk. You’re so cute when you stutter.”

Young Roy’s income during this period must have been important to his mother and their family, who lived on a “shoestring.” At some point Charlotte may also have taken in boarders, including women friends her age, but it is not clear when this started — perhaps as Nettie’s and Roy’s rooms became vacant. Charlotte, still a widow, had a hard life. She had to pinch pennies and deny herself many things to keep her little family going. In Grass Valley she had joined the Eastern Star, a Masonic Order; she rejoined in Berkeley in 1902, and this brought her new friends and comfort. Her children were also Masons in Berkeley. In 1907 Nettie gave Charlotte a trip to Honolulu, Hawaii, with a group of Eastern Star ladies. It was the biggest trip of Charlotte’s life. Nettie paid for it when she made a little money selling real estate.

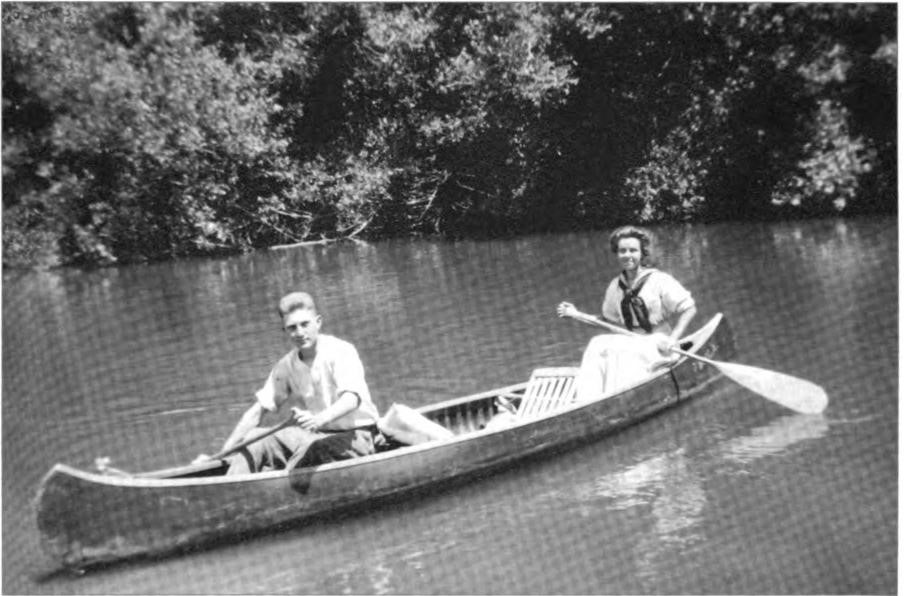

In 1907, a year before he went to college, Roy met Hazle Lawton, his bride-to-be. He was 20 and she was a “popular young high school girl” of 17. Born on 25 September 1890 in Berkeley, California, Hazle was the daughter of Frank H. Lawton and Fannie Rogers. Frank was a real estate agent and builder in Berkeley. The Lawton family also lived in Berkeley, at 2211 Durant Avenue between Ellsworth and Fulton (near the southwest-corner of today’s Edwards Field, the Cal track stadium), and only about eight blocks from the Shurtleff home on Hearst at Oxford, a short walk. At Berkeley High there were apparently women’s sororities in those days, for Hazle was a member of Alpha Sigma. Hazle’s older brother, Harry Lawton, had been one of Roy’s closest friends since Berkeley High School days. But Harry persistently called Roy “Shirt-tails,” and this once led to a long fight lasting all afternoon, until it was finally “called on account of darkness.”