** All Text on these chapter pages has been copied verbatim – with permission – from this book: “Shurtleff Family Genealogy & History – Second Edition 2005” by William Roy Shurtleff & his dad, Lawton Lothrop Shurtleff ** Text in pdf convert to word doc – any spelling errors from the book may or may not have been fixed. **

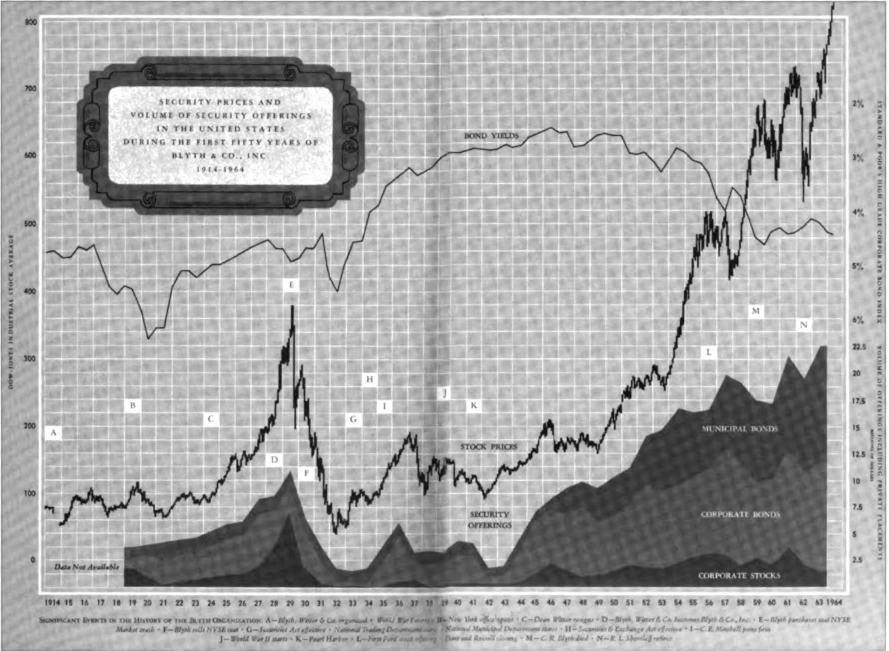

In late October of 1929, the stock market crashed. On the day of the crash, Roy and Hazle were traveling in Tijuana, Mexico. Lawton was almost 15 years old, Gene 12, and Nancy 10. The bubble had burst and a period of panic ensued. Thousands of fortunes (especially those based on credit) were wiped out, and numerous families were plunged from the heights of new-found wealth (financed by excessive borrowing against extravagant market prices) into poverty, as the market collapsed.

However, in late 1929, the market began what looked like a strong recovery. People started to regain confidence and to reinvest. During January 1930 Herbert Hoover declared that the trend of business was “upward”; in March, that “the crisis would be over in 60 days”; and in May that the nation had “passed the worst” and “would rapidly recover.” Yet hindsight reveals that by May 1930 the market was beginning a headlong plunge that did not stop until mid-1932. This was the really big crash; it ended up doing the immense damage that became known as the Great Depression.

The Depression affected the Shurtleff family considerably. It also destroyed the lives of many people they knew well in Piedmont. The head of one prominent family, whose children played with the Shurtleff kids, committed suicide with a bullet to his head. Nancy recalls that Mr. Blackaller in Piedmont jumped out of a high window in his home. Another man, Leslie Henry, a close friend and Blyth employee, ended up embezzling his clients’ funds to pay his own debts. Roy was eventually forced to testify against him in court, and Henry ended up in San Quentin prison for several years.

No one knew at the time how to evaluate the severity of the crash or how long it would last. It was typical of Roy that he reacted both quickly and decisively. At Blyth, all of the officers took major salary reductions. Roy’s salary was cut to $800 a month, from about $4,000 a month ($50,000 a year), an 80 percent cut. At home, Roy acted to reduce expenses. All of the household staff (cooks and maids) except the chauffeur were dismissed; fortunately some were immediately rehired by close friends. Roy kept his chauffeur, rather than let him join the bread lines, until he found him other employment. Memberships in the Trail Club, the Pacific Union Club, and later the Claremont Country Club were dropped and the family horses were sold. Roy had been a member of the Pacific Union Club since 1924 so this was a great sacrifice for him. The Wells Fargo Bank granted Roy a holiday on payment of his loan. But the children were not taken out of their private schools until mid-1931.

Roy and Hazle called a family meeting at which Roy explained the severe reduction in his income and Hazle set forth what would have to be drastic changes in the family’s lifestyle. Hazle was to become the cook and maid, sharing household chores with the children, who would keep their own rooms clean and help in the kitchen. Nancy recalls how, in those days, Hazle often set up an ironing board in the upstairs bedroom and stood there ironing at night while she and Roy were having their evening cocktails. Roy would take charge of the garden and the cars. He planted flats of flowers—stocks and snapdragon—each spring in Piedmont so that the front yard blazed with color. Lawton and Gene were given their first regular chores: helping in the garden on weekends, cutting lawns, raking and burning leaves, and washing cars. The children’s former allowances would be replaced by a wage of 50 cents per hour to support their personal needs. Even at Tahoe they typically had to work two to three hours each day before they could play.

Picture – Two young entrepreneurs, Pat Harrold and Lawton Shurtleff, acted immediately to fight the Depression.

They formed a business corporation and began washing cars for 25 cents each plus the loose change they often found behind the seats or on the floor.

They washed a lot of cars, but it is not known how much ready cash this produced.

Lawton and Gene were in school at Tamalpais when the stock market crashed. Lawton later wrote: “However mediocre our academic achievements, it was literally impossible in those days not to get an excellent education at this small private school, with Paul Temple teaching history, Davidson in Latin, Estes in math.” Meanwhile, Lawton discovered for the first time that he was a good athlete. In fact, he soon became a star. He captained the baseball team as a pitcher, the basketball team as a guard, played fullback on the football team, and for two years was elected to the All-Conference teams in baseball and basketball within the Private School Conference of Northern California. This conference consisted of six relatively small private schools: Tamalpais School, Montezuma Mountain School, San Rafael Military Academy, Menlo School, Damon School, and Bates School. A local scout even suggested that Lawton try out for professional baseball.

But this sudden and unaccustomed fame turned out to be a little more than Lawton could handle gracefully. “Looking back on those years,” he later wrote modestly, “it is clear that it did not require great talent to be a star with a total of only 60 to 70 boys in the entire school.” Lawton also later apparently had second thoughts about the long-term value of being a standout in major high school sports, for he strongly discouraged his own sons from following in his footsteps, suggesting instead that they go out for sports with long-term benefits such as swimming or tennis and not neglect their studies.

Lawton was also the first junior to be elected to the Boy’s Council at Tamalpais. He later recalled: “In my new position I reported every infraction of the school rules that I could find. I felt that this was my responsibility and I carried it out with great zeal. My fellow schoolmates, however, had not anticipated that I would be quite so officious. In the election for a second term, I was overwhelmingly defeated by a whimp named de Fremery. This was one of the first great disappointments of my young life.”

Lawton rarely failed to make a strong, clear impression on those who knew him. A unique individual who liked to do things in his own way, he had both his admirers and his critics. They described him variously as “cocky, conceited, a complete nonconformist who enjoys the role, very creative, bright, talented and interested in ideas but not using his potential academically, in an ongoing confrontation with authority, a tough ompetitor or adversary, lacking humility, self centered, stimulating and dynamic, very handsome, surprisingly insecure and lacking confidence in himself, somewhat of a loner.” Lawton later recalled in a moment of candor:

Yes, cocky was the term they always used to describe me in those days. I always felt that my so-called cocky or arrogant attitude was from a deep-seated insecurity and lack of self confidence. I developed what they called a “punk attitude,” which carried through much of my life. At Tamalpais I spent every waking hour, yearround, on sports. I read and wrote a great deal from the very beginning. I might have been capable but I simply never studied. Thus my contribution was athletic, never scholarly, and I got an F in application or deportment. I was never allowed off the Tamalpais campus on weekends for disciplinary reasons….except at Christmas.

Like his children, Roy had his own mischievous streak: home brewing. He stepped it up during the years of Prohibition and the Depression, to save money, ensure quality, and sidestep Prohibition on the sale or manufacture of liquor in the U.S., which remained in effect from 1920 to 1933. In addition to beer, he and the kids made dozens of cases of root beer and what the family called “Coke.” They prepared it in the kitchen, then aged and stored it on the shelves of his large and marvelously temperature-controlled liquor closet/wine cellar in the basement. The nonalcoholic brews entertained the neighborhood teenagers through the summer months. Gene remembers how he would occasionally hear the beer bottles pop their corks and also how the local bootlegger would back his car up to the basement door and unload the booze into the liquor closet.

In the affluent years before the Depression Hazle had developed an unusual fondness for material things. As Gene remembers (and Lawton agrees):

When Hazle didn’t have anything else to do, she’d go shopping. She became a fantastic shopper, who loved to spend hours on end buying clothes, china (porcelain dishes), expensive antique furniture (after 1936), knickknacks, and the like. Her good friend Miss McGrath, the head sales woman at I. Magnin in Oakland, always kept an eye out for interesting new goods and would phone her when they arrived. She was on a first-name basis with numerous sales people at other exclusive little boutiques. She continued this expensive pastime throughout her life, alone and with various woman friends, and eventually bequeathed it to her daughter, Nancy, who is reputed to have 5-10 times as many dresses as most women.

(Nancy disagrees! She feels that Hazle never went overboard in her shopping, and notes that many of her own [Nancy’s] Piedmont contemporaries have as many clothes as she does.) Yet in the years of austerity Hazle toned it down only slightly. Lawton recalls: “During the Depression, when 1 was assigned to pay the bills, I frequently got irate at all the money mother was spending on what seemed to be frivolous stuff.”

As the stock market continued to fall, work at Blyth was extremely stressful for Roy, and he’d often arrive home exhausted. One day when Nancy was about 12, she asked him if he’d like to play solitaire with her after work. As Nancy (Nance) remembers it:

Although Roy was not the kind of a person who usually wanted to just sit down and be sort of familyish, he said he would. So we’d often sit there in the big living room, just the two of us, and play solitaire before dinner. It was kind of amazing. He just loved it and he spoke of it often in later years. 1 never felt closer to my father than during those times.

In 1930, as the Depression worsened, Nance was taken out of private school at Miss Ransom’s and transferred, in the sixth grade, to Frank C. Havens School, a public grammar school in Piedmont. This was a blessing, for there she met Willard Miller; it was love at first sight and they were eventually married. In 1931 Nance and Willard started junior high school at Piedmont High, and in 1933 they both began high school there. During this period Nance’s life revolved around Willard and her small group of five or six close girl friends from Piedmont. As Nance recalls, “I was not very gregarious or extroverted; I stayed to myself and with my friends. I was never a good student, and never interested in academics.” Others who knew Nance remember her as popular, attractive, congenial, one who liked to have fun, a good sport, willing to try new things (like skiing or water skiing), often adventuresome.

Also in June 1931, at the end of the school year, Lawton and Gene were taken out of private school at Tamalpais. In the fall they enrolled in Piedmont High; Lawton, age 16, was a senior and Gene, age 13, a freshman. Lawton later recalled that academically, senior year at this public school was like repeating sophomore year at Tamalpais. Again Lawton starred as an athlete in football, basketball, and track; this became the key to his social success. He was also elected to one of the two positions on the Boy’s Council, where again he now feels he was overly officious.

Since Tamalpais had been a boys’ school, it was at Piedmont High that Lawton began to take his first interest in girls, an exciting new subject introduced to him by his lifelong buddy from Tam, Pat Harrold. By coincidence his first date was a pretty blonde girl named Peggy Birbeck niece of Harry Lawton’s first wife, Joyce. Pat also got Lawton into one of Piedmont High’s two boys’ clubs, Kimmer Shielding. When invited at Leap Year to his first dance by Jane Gabriel (whose father was a friend of Roy’s), Lawton pretended to limp all night, since he couldn’t dance and wouldn’t admit it. Gene recalls that Hazle offered Lawton use of the family’s Cadillac limousine if

he would take the daughter of one of her very close friends. Later, when Lawton and Jane appeared to be getting too serious, Roy put a damper on the romance by warning that “Jane will probably turn out looking like her mother.” In a similar vein, when one of the neighbors’ children got into trouble, Roy mused, “What else could you expect from a mongrel marriage,” for the mother was of Hawaiian descent.

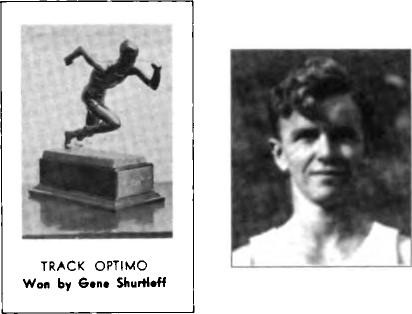

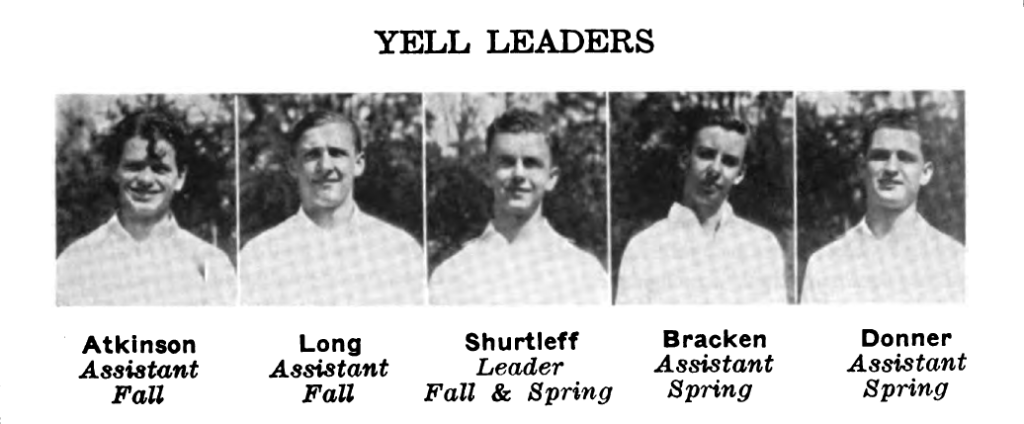

When Gene started high school at Piedmont High in 1931, he had largely overcome his various childhood problems, except for occasional attacks of hay fever. During the next four years, he began to come into his own, in fact, to blossom. After trying various major sports his freshman year, Gene started to concentrate on pole vaulting as a sophomore. The track coach, Brick Johnson, felt he had potential, and Gene worked at it year round. He gradually developed into a fine athlete. His senior year he vaulted a little over 12 feet, making him number one in the school. A generation earlier, that would have been a world record. He was also a good swimmer. In addition to earning his letter in track, he was awarded the Track Optimo, the highest honor given in track (as in each major sport) for outstanding athletic ability, sportsmanship, and leadership.

He was an assistant, ” yell”, leader for two years, and head ” yell” leader his senior year. He was also chosen president of Kimmer Shielding and served as a member of the Student Council.

Those who knew Gene during this time remember him as “one who followed the rules (never a nonconformist or troublemaker), wanted to be a solid respectable citizen, and contribute what he could.” Lawton added: “In high school, Gene was a very outgoing, popular and well-liked person. Ours was generally a humorless family, except for Gene. He could get the whole family completely broken up in laughter. I can still see him doing his caricature of the kid lisping as he recited:

My favorite indoor thport is thpitting

I can thpit in thircleth and thpiralth

and in and out of doorwayth

I have a friend

Hith favorite in thport is thpitting too…

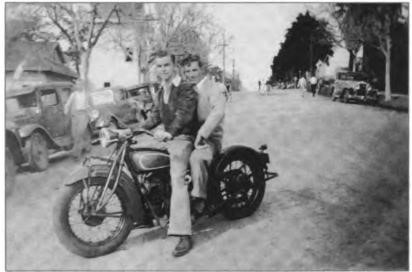

During his senior year, using money earned as a summer messenger boy at Blyth & Co., Gene bought a little Indian motorcycle. He rode it to and from school, and on numerous trips, including one to Utah, where he cracked it up and had to ride back with friends. In the fall of 1935 he entered the University of California and (like Lawton) joined the Delta Upsilon fraternity.

(picture – Gene traveled far and wide, often with Ben Reed or Dudley Dexter, on his little red motorcycle. Circa 1934 at 209 Crocker Avenue, Piedmont.)

The boys had been away from home in private boarding schools for most of the past five years. Now they began living at home.

In mid-1932, with only a month left before graduation at Piedmont High, Lawton received a phone call one night at about 10 from his chum Bob Henshaw, asking if he could leave next week for a trip around the world as a seaman on the Dollar Steamship Lines. (The Dollar family, coincidentally, lived less than a block away from 209 Crocker Avenue) As Lawton recalls:

I told Bob to hang on a minute while I asked my mom. I ran up to my parents bedroom only to find them both (to my great embarrassment) together in one of their twin beds. I blurted out my question about going around the world next week—not a common thing for a high school student to do in 1932. It could well have been the circumstances surrounding the meeting, but the answer was “Yes, of course,” without any further discussion.

After returning from the eventful trip, Lawton enrolled as a freshman at Cal Berkeley. He was supposed to have gone to Princeton, but the Depression made that too expensive for the family. He was pledged by the DU fraternity house on Warring Street. Enrolling late after his ’round-the-world trip he was ineligible for all freshman sports. This greatly handicapped his career in sports. As a result, he did not go out for any varsity sports, except briefly for baseball and basketball, without any conspicuous success. He continued his love of reading (“I practically lived in the library”) and concentrated on the heavyweights, like James Joyce and Steinbeck. He especially enjoyed the reading and writing of poetry (Robinson Jeffers, Edna St. Vincent Millay) outside of classes, but he missed many classes on the sprawling campus and maintained only about a C grade point average, largely for lack of self-discipline.

During college Lawton became a flaming liberal, just at the time when Franklin Delano Roosevelt was starting to make business a dirty word. Lawton took a special interest in labor relations, and the development of labor unions in the United States and particularly John L. Lewis and his newly formed CIO. He got good grades in these subjects. He found the home dinner table to be a great place to air some of his new pro-union, anti-business ideas, which of course led to heated discussions with Roy. But before these exchanges could reach the level of dealing with the basic philosophical issues, Roy would terminate them tersely with something like “You’re absolutely out of your mind. Your professor must be a Red.” Roy’s line of reasoning must have been persuasive, for in later life, Lawton came to regard liberals with about as much favor as Roy did.

These weekend political arguments between husband and son were hard on Hazle, whose emotional equilibrium was easily upset. As Gene recalls: “We’d all be sitting at the table, with no one else saying a word. It finally got so heated between Lawton and Roy that Hazle would burst into tears and go running upstairs. She just couldn’t take it any more. You’ve heard Lawton argue. You know how he can upset people!”

Nevertheless Lawton graduated from Cal in June of 1936 with a B.A. degree and majors in economics and English. He did well enough to be accepted upon graduation to Harvard Business School. “They were undersubscribed,” he explained modestly.

During the hardship years of the Depression, Hazle showed, more than ever, her great kindness to others (including her children), compassion for their suffering, and unusual sensitivity to their feelings. In many cases, her caring was remarkably creative. A few examples will suffice.

Hazle’s older sister, Winnie Lawton, a devout Christian Scientist, had had a bad marriage to Bernie Seymour, who is remembered as a “real tough, arrogant guy.” They had four children, then were divorced. The two oldest children, Bimelyn and Jack, who were in approximately grades 8 to 10, were having a hard time dealing with the separation. So in about 1930 Hazle and Roy suggested that they come live with the Shurtleff family for a year and attend school in Piedmont. To introduce the newcomers to the other kids in the neighborhood, Hazle got permission to cordon off three blocks on Crocker Avenue and hold a street dance! No one had ever heard of such a thing but it was a great success. In fact it was so successful that in 1987 it was still being held, and called Crocker Capers.

In early 1930 Hazle’s mother, Fannie Rogers Lawton, was suffering terribly from stomach cancer. Her husband, Frank, went through hell watching her pain and could not care for her alone. So Hazle and Roy took her into their home on Crocker Avenue and Hazle cared for her for six to nine months until she died there on 7 November 1930, at age 71.

A friend of Roy’s named Leslie Henry, a salesman in Blyth’s Los Angeles office, had been convicted of embezzlement and investment fraud while trying to support his family during the Depression. He was sent to San Quentin prison. His wife had long been a close friend of Hazle’s, having been the matron of honor at her wedding. Hazle would invite Mrs. Henry to stay at the Crocker Avenue home on many a weekend and Hazle would go with her to visit him in prison.

In 1934, when Nance was in ninth grade at Piedmont High, Hazle began to feel that her attractive daughter was too much of a loner. Nance had her own little group of four to six close friends (many of their parents were friends of Roy and Hazle’s) but Hazle felt she should get to know more people her age and spend less time reading pinup and movie star magazines. So in December of that year Hazle organized the Junior Assistance League (JAL). Its members were chosen from among girls who were leaders in Nance’s grade or the next higher grade in high school. The JAL led Nance to meet many older Piedmont girls, some of whom are still close friends. The JAL made things like dish towels, sold them, then donated the money to a pre-existing group called the Lincoln Guild, which used it to provide financial assistance to a home for unwed mothers in the Bay Area. The Junior Assistance League (now called the JA) is active to this day and its membership is considered a great honor for Piedmont girls. In fact, one of Nancy’s granddaughters became a member of it.

In 1934 Roy and Hazle felt that Nance was getting too close to Willard. So as a freshman in high school (ninth grade), after she had been at Piedmont High for only six months, they sent her to Castilleja, a private school in Palo Alto. Nance was now old enough to start showing her true Shurtleff colors. She rebelled! As she later recalled candidly:

1 hated the place. I hated the uniforms and all the rules, and wanted the security of home. I only wanted to be with Willard. So I ran away from school. Shirley Makinson came with me. We then escaped from the police on a train, but eventually we were picked up by the cops in the Ferry Building in San Francisco, handcuffed, and taken back to school. So 1 escaped again. In grammar school and high school I was a terrible person! But none of my friends ever thought of me as wild or bad. They thought running away from Castilleja was just hysterical. Like “Nice going, Nance!” They still laugh about it. I also recall at Tahoe in the early 1930s that my friends and I would enjoy gin and tonics, as a prank in the afternoons, when my parents were away.

Nance ended up staying at Castilleja for only about six months. Though Hazle was not very well at this time, she was very understanding throughout all of this. But little did she know that Castilleja was not the last prestigious private school her daughter would run away from.

Roy and Hazle apparently did not agree with Nancy’s friends’ praise for her rebelliousness. In Nancy’s confidential dairy from 1934 we find again and again, “I don’t understand why they are punishing me. I guess I was bad.” One time the tragic soap opera conclusion reads: ” I don’t know what I should do, but I guess I will kill myself and end it all!”

Looking back, it is fair to say that the Shurtleff family did not suffer great hardships during the Depression. Most members were strengthened by the adversity. Appearances were kept up, in part by foresight, good planning, and individual effort.

The Depression, however, seems to have substantially changed Roy’s attitude toward money. During the affluent years at Crocker Avenue he and Hazle had lived high on the hog—never ostentatious, flamboyant, or showy, but certainly high class, and at a level that was typical for San Francisco bankers of his means and station. Gene recollects:

Roy was also influenced by his wife. Hazle liked fine things, pretty dresses, the best dinnerware, a nice home, and she was aggressive about getting these things. But after the Depression they not only went to a totally different style of living, but their attitude toward money changed. They took less interest in personal possessions, were more conservative. Roy wanted to live within his means, stay out of debt, and protect his heirs. Never lacking in generosity, he outgrew his acquisitive interest in luxury cars, expensive clubs and the like.

Lawton remembers Roy returning one day from cruising alone in his speedboat on Tahoe and remarking: “You know, the things you own don’t bring you much pleasure. The speedboat hasn’t really brought me much pleasure.” Lawton also recalls that during the Depression, Roy finally paid off the last of his many debts by selling some of his Blyth stock, mortgaging the Piedmont house, etc. He announced at the time with a great sense of relief: “At last we don’t owe anybody in this world even one thin dime.”

One effect of the Depression was the great increase in labor union activity. In San Francisco Harry Bridges, a card-carrying Communist, was militantly organizing the dock workers. Piedmont was well known to be the home of the wealthy, and 209 Crocker Avenue was near the boundary line where the conspicuously large houses began. At one point rumors began to spread that the dock workers were going to attack this affluent area. Roy often told the story of how he and other homeowners from the surrounding area took their stand by sandbagging the Mandana Boulevard-Crocker Avenue battle line directly below Roy’s house. A veritable army of Piedmont’s millionaire gentlemen showed up, armed with baseball bats, rakes, hoes, and the like, to defend their property against the imagined and feared Communist invaders. The mood was deadly serious and tense. Unfortunately for storytellers, nothing happened, but even that story brought many a laugh in later years. Yet Harry Bridges’s type of unionism and general strikes did have their long-term effects. They reduced San Francisco from the West Coast’s leading harbor in the 1920s to one of minimal importance in later years up to the present.

Oakland, Los Angeles, and Seattle ended up with most of the shipping business.

The Great Depression caused tremendous hardship at Blyth & Co. It was at its worst during the years 1930 to 1934, and much of Blyth’s earnings from the 1920s were lost. In early 1930 Blyth terminated its brokerage business and sold its seat on the New York Stock Exchange. It was once again an investment banking business. In March 1933 Franklin Delano Roosevelt was inaugurated as president. Radical changes in the banking and business worlds ensued. Reconstruction of Blyth began in 1935.

In June of that year, Charlie Mitchell was employed as Chairman of the Board. He ran the New York office, which soon was officially designated as the head office. Mitchell had been president and later Chairman of the Board of the National City Bank of New York, and was widely considered to be one of the most powerful people on the American financial scene. As a Blyth history later noted: “Perhaps because of his power and prominence, he was made a whipping boy for Wall Street by politicians. He was charged and convicted with tax evasion by the Federal Government and he came to Blyth with a great burden of personal trials. He was a man of great ability, courage, and steadfast principles. His contacts in Wall Street were invaluable.” Roy Shurtleff later recalled that in October 1935 Mitchell brought Blyth its first great national underwriting, $55 million of sinking fund debentures, for Anaconda Copper Mining Co. This key underwriting and other activities of Charlie Mitchell’s helped transform Blyth from a West Coast organization to a national one of greatly enhanced stature. Indeed, Blyth & Co. was the first West Coast investment banking company to achieve national, and ultimately international, prominence.

Not long after Charlie Mitchell was hired, Lawton Shurtleff, in dinnertime political discussion with Roy, accused him of making a “jail bird” chairman of the board at Blyth. Roy, who was absolutely furious, excused Lawton from the table to go to his room and not to return until he had prepared a proper apology. Later, in 1938, Charlie was Lawton Shurtleff’s immediate boss at Blyth in New York City.

In 1935 Charlie Blyth asked Roy Shurtleff to organize a national sales department with head quarters in New York, and to become National Sales Manager. Roy was initially reluctant to leave California and to sell the family home on Crocker Avenue in Piedmont, where the family had lived for ten years. Yet perhaps he hoped that a complete change of scene would be beneficial to Hazle’s health and outlook on life. So in November of 1935 Roy and Hazle traveled to New York to see if they wanted to live there. They decided to try it, so they found an apartment. In December they shipped all of the furniture out of the Piedmont home to New York, then moved into the Claremont Hotel, where they celebrated a sad Christmas before leaving for New York.

Nance, especially, hated to leave Piedmont, her tight circle of friends, and Willard. One of her close friends, Jean Campbell, later told her: “When you left, we all felt we had lost our leader. You always did everything first, and we all thought that whatever you did or said was right.”

Before going on, let us gather some remembrances of Hazle and Roy from this period. Martha Haven (age 16 in 1934), who was dating Lawton, recalled in 1986: “Hazle was very gracious and warm. She was Berkeley type, not a Piedmont type, more friendly and direct than most socialites. She was easy to deal with; no up-tightness or artificiality. She was never sick when I was there. Roy had a lot of charm. I always adored him. Yes, charm is the first word that comes to mind when I think of Roy. He was reserved but very friendly with me.”

Lillian Haven had known Hazle since their sorority days at Cal. In 1986, at age 94, she recalled:

Hazle invited me to Tahoe twice in the mid-1930s with a small group of her lady friends, including Madeline Clay Harrold and Emily Milligan, Solinsky. Roy was not there. Both visits were happy and natural easy fun. There were no signs of a heavy heart by Hazle. She let down her hair, and each time we all laughed and laughed. One time we couldn’t stop for an hour; we had an hilariously good time. Hazle had a wonderful sense of humor. She was fun to laugh with and laugh at; she never took umbrage, and never got mad at us. We called her Mrs. Malaprop. She wasn’t an A1 student. She’d make mistakes, and we’d all laugh and laugh. My association with Hazle was always exceptionally warm, fun, and admiring.

I think that Hazle was in love with Roy, but I always had the feeling that she was having to make a supreme effort to be in an entertaining, social role that was very shallow and vapid. Hazle was much more earthy. I always gathered that she would have preferred to lead a simpler, more natural life and not to have to struggle to make everything be just so. She was not so comfortable in a role she had not been brought up with. She was out of her element, but she did what had to be done.

As for Roy, I was a little afraid of him. I thought he was reserved, but I didn’t know him well. He had great dignity and aplomb. He was good looking and had sufficient savoir faire to carry him anywhere he wanted to go.

It is interesting to note from the above that Hazle apparently enjoyed both the life of luxury (described by Gene) and the simpler life (described by Lip. As her son Lawton recalls: “During these years Hazle was happiest when she had an elephant to wash—a BIG project to work on. Many of her children and grandchildren seem to have inherited this trait from her. I often heard that she had a good sense of humor but she almost never showed it to her family.”