** All Text on these chapter pages has been copied verbatim – with permission – from this book: “Shurtleff Family Genealogy & History – Second Edition 2005” by William Roy Shurtleff & his dad, Lawton Lothrop Shurtleff ** Text in pdf convert to word doc – any spelling errors from the book may or may not have been fixed. **

In early 1925, just as the stock market was starting a dramatic rise that would last until late 1929, the Shurtleffs moved to the area of “new wealth” in Piedmont. The Peninsula was considered the area of “old wealth” in those days. On 2 January 1925 the family (in Hazle’s name) acquired title from Frank and Flora Proctor to a beautiful new home at 209 Crocker Avenue, high in the prestigious Piedmont hills overlooking San Francisco Bay and just a mile and a half as the crow flies east of their former home on Euclid Avenue in Oakland. Built just before they moved in, this residence was in the most highly regarded residential community in the East Bay. It was a newly developed area, having been mostly farms as recently as 1920. A streetcar ran from Piedmont Avenue right up to Crocker Avenue, a few minutes’ walk from the new family home.

The Shurtleff’s Piedmont house, 209 Piedmont Avenue,1925. It’s obviously new since there is none of Hazle’s lush planting of later years.

The house was a three-story, 4,500-square-foot, Tudor-style half-timber mansion, with gabled roofs, towering brick chimneys, and five fireplaces. On the first floor was a library, large living room, dining room, breakfast nook, kitchen, pantry, and servants quarters for two live-in couples (indoors off the back of the kitchen). On the second floor were four bedrooms, one for Roy and Hazle, one for Gene and Lawton, one for Nancy, and a guest room, plus separate dressing rooms for Roy and Hazle, and several bathrooms. The large third floor attic was converted to a playroom, which eventually housed a large electric train. Downstairs was a big unfinished basement, later converted to a family game room. (The “subdued Tudor” was later featured in the 26 December 1976 edition of Oakland Tribune Home.) The house was one of two built by Frank Proctor. For decades thereafter, until the early 1980s, it was on the Piedmont Home and Garden Tour, and always known as “The Shurtleff Home.” It was a lovely and spacious house, tastefully decorated by Hazle.

Right after the family moved in, Lawton (age 11) and Gene (age 8) had a chance to show that they were becoming a bit more sophisticated in their hell-raising. As Gene remembers the unforgettable experience:

We were with two older kids; one of them, Larry Magnussen (who was a really bad guy), got us into it. I just kind of tagged along with Lawton and the bigger kids. Anyway, we went over to the other big house in the neighborhood that was just like ours (it was also built by Frank Proctor) and we literally destroyed it. We broke every single window in the entire house. We just went out of control. When Roy heard about it he took us down to the basement, took out his razor strop, and just whipped the hell out of us, till we felt we could hardly stand up. Then he sent us down to Mr. Proctor, made us apologize, and made us pay him $10 a month out of our allowance for the next two years. The whole thing was totally inexplicable. It was one of the worst things we ever did.

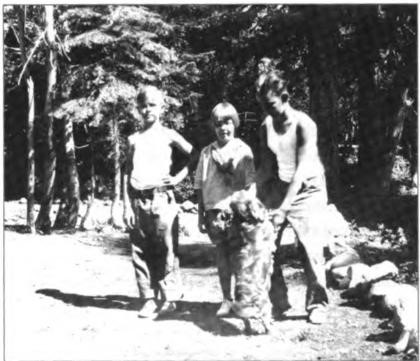

Gene Shurtleff recalls that when the family lived at Crocker Avenue, they had a cocker spaniel name Roxie. This must have been because when Roy was younger, he had his first cocker spaniel also named Roxie.

The first live-in help was a Japanese couple named Sam and Karmi (he did all of the cooking and heavier house work; she served and did light housekeeping), and James, the chauffeur-handy-man. They lived in the rooms off the back of the kitchen. Someone else came in to take care of the garden. James was a large fellow, strong enough to later carry large rocks to line the family driveway at Homewood, Lake Tahoe. He was succeeded by Jim, who drove for the family until the Depression. Then there was the governess Mrs. Henderson (“Hendy”), who took care of Nancy. She often commuted to her home in Hayward and she also worked for another family, the Andrews. When Sam and Karmi returned to Japan, they were replaced by a Philippine couple, Juan and Sherry.

Shortly after the Shurtleffs moved to Crocker Avenue they joined the Claremont Country Club, a gathering place of Piedmont high society. The club had its own golf course, and golfing was an important activity for the Piedmont social set. So Roy played golf with the Hawleys, Proctors, Cavaliers, and others, who also belonged. Roy never became a very good golfer. In about 1947 he finally turned his golf clubs over to Gene saying, “Here, you can keep these damned things for the rest of your life and be frustrated like I’ve been.” Some of Roy & Hazle’s children (Lawton’s and Nancy’s families) later became members of the Claremont Country Club, and were still members in 1987.

Horseback riding was also a major Piedmont social activity, and many of Roy and Hazle’s friends had horses. The Shurtleffs first began to ride horseback in the Bay Area at the Piedmont Riding Stables, using the stables’ horses. This private group acquired new land, built new stables down in Redwood Canyon (on the eastern side of the Coast Range), and was renamed the Piedmont Trail Club. The Shurtleffs may have been one of its founders; there they owned and boarded their horses. In about 1926 Roy bought his first horse, named Captain, at Brockway and had him shipped to Piedmont. After Roy eventually sold him, he became a well-known jumper in horse shows. A second horse, ridden by all the family members, was Mancha (pronounced muh-ROO-ha), purchased in Sacramento. A third horse, named Trixie, was ridden mainly by Gene. Most of the family riding was on club trails on the property above the stables and in the wild canyons (such as Redwood Canyon) on the sparsely populated eastern side of the Coast Range. They also rode occasionally up in the hills along Skyline Boulevard near Miss Graham’s stable. Roy became an exceedingly good rider. He twice won the Piedmont Trail Club Paper Chase, where he had to follow pieces of paper set out in the woods in advance, in place of a live fox.

Roy had grown up in a fatherless family without many traditions, so he worked to establish some memorable ones in his family. One of these was big Christmases with lots of presents. Roy recalled in 1963: “Then there was the bicycle and basket ball era at Crocker Ave. when we used to march to the tree, the youngest first, after a hasty breakfast.” One Christmas Roy surprised the entire family by having part of the basement entirely refinished with knotty pine paneled walls and hardwood floors. Furnished with a full-sized pool table and a ping-pong table, it soon became the games room and entertainment center for the neighborhood. Shooting / sailing baseball cards toward a wall, a game called “Zeanuts”; the cards came in a package of Zeanuts candy), or sailing milk bottle tops, was also popular on rainy days. Complete with fireplace, the room was used for occasional high school parties and dances.

Another Christmas in the late 1930s, Roy surprised Hazle by commissioning a fine woodcarver and cabinetmaker to create an imposing dining room set of furniture, including a large table with 10 chairs and a huge sideboard. The set was unveiled on Christmas morning and, as Gene recalls, Hazle was unable to control her disappointment, because she had been longing for an English antique set made by Sheridan. Roy, of course, was crushed.

In January 1926 Roy and Hazle went to Peru to negotiate a bond issue for the Peruvian government. When the family had moved to Piedmont, Lawton and Gene had first attended the Frank C. Haven School, a public school one block north of Piedmont High. From there they went to Piedmont Junior High. Now, before Roy and Hazle left for Peru, they sent their boys to Montezuma Mountain School, a private boarding school in Los Gatos, on the northern foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains. One of the early private schools in northern California, Montezuma had a good reputation for academics and discipline. Lawton was 12 years old and Gene 9.

Lawton’s behavior remained true to the pattern established over a youthful lifetime of unremitting mischief. As he later reminisced, half proudly: “I was always in trouble at Montezuma. We were constantly doing crazy things, like short sheeting beds.” (Note for modern innocents: This involves replacing the typical two sheets on a person’s bed with one, but folding it back up halfway down the length of the bed, so that it appears to be two. When the sleepy victim of short-sheeting climbs into bed at night, his feet hit bottom only halfway down. He is rudely jolted into realizing that he must get up and entirely remake his bed.) At Montezuma, those who misbehaved (swearing, fighting, pranks, etc.) or failed to complete their assigned chores had to do laps, initially around a lake and at a later period at a flat track up on a hill. A monitor counted the laps. Lawton continues: “I know I had to do more laps at Montezuma than anyone else in the school.” Gene thinks that he was second, after Lawton, in total laps, thus keeping the dubious top honors entirely within the Shurtleff family.

When the boys returned home to Piedmont after Montezuma, Roy liked the idea of laps. They provided valuable exercise around the large family house, were a little less violent than thrashing with a razor strop, and required less time and attention to detail than “the book.” Laps were given for talking back, losing one’s temper, swearing, or failing to do what one was asked to. Gene often remembers Roy saying to him: “Go do 20 laps.” Nancy, feeling sorry for her brother, sometimes accompanied him on his laps. This is not to say that Roy discontinued spanking.

Though the worst thrashing followed destruction of a neighboring home at Crocker Avenue, Lawton recalls:

We were spanked when we deserved it. Roy would say “Okay, take off your belt and drop your pants.” Or, less frequently, “Let’s go out and cut a switch.” Then he’d just switch the holy hell out of you. We’d be jumping up and down with that little switch or belt just stinging our bare legs something awful. It was almost worse watching the other guy get his—knowing you would be next.

(picture – Nancy at the rear of the Shurtleff’s Piedmont home, now covered with ivy, with one of Hazle’s collies, probably Rudy, circa 1937.)

Although Roy administered the corporal punishment, Hazle took most of the responsibility for molding the character of her children. She set the standards of conduct, guided family morals, and educated on etiquette and sex. She had very high standards herself, plus a strong character and forceful leadership. She was the one who took the kids aside individually to explain the facts of life or give one a good talking to. She expressed herself well. She organized family activities and work, believed that the family should work together, and inspected the finished work with a boot-camp sergeant’s eye. When the kids were home, they were required to work in the garden each Sunday morning with Roy and Hazle. Lawton recalls: “It was so frustrating when all of our buddies would be standing in front of our home just waiting until we could join them for an afternoon of fun or relaxation.” The closest Hazle came to meting out discipline was to occasionally wash a kid’s mouth out with soap if he or she was caught swearing or talking back. Nancy recalls that there was also a system for grading the kids behavior during the first four or five years at Crocker Avenue. A record was kept posted on the wall and it was maintained by the governess and given more emphasis when the parents were away. Summing up, Lawton notes: “We were well disciplined. Before the Depression we didn’t have a lot of household chores to do; the family help did that sort of thing. But we did have to watch our table manners.”

In those prosperous, golden years before the Depression, Roy found time to balance his own recreation with a demanding work load. Golf, horseback riding, and work in the garden were his creative ways of relaxing. While in college, Roy had become an expert at punching a punching bag (the type used by boxers); he learned all the trick punches, elbows, etc. At Crocker Avenue he constructed a punching bag set up in his basement and used it for exercise. Later his kids learned to use it, and built similar ones after they were married. The William Wheelers had a full sized tennis court on the lot next door to the Shurtleff house. Roy and Lawton often played there; Roy always won.

At Crocker Avenue, Lawton and Gene spent a great deal of time raising animals. They started with a setting hen, purchased at Mt. Diablo, which hatched and raised her chicks in the basement. Before going to Montezuma, Lawton had built a pigeon coop in a far corner of the backyard. There he raised pigeons. But as Gene remembers it, “We both worked our tails off for those pigeons. Lawton always considered me, his little brother, as an assistant, and had me do all the damned dirty work. I fed and watered them, watched them, fed the babies, the whole works.” Lawton responds “Oh, yeah?”

After returning from Montezuma to Crocker Avenue, Lawton decided to diversify into ducks. But where to get the eggs? As he recalls unabashedly, in fact proudly: “We’d swipe ’em.” To make the trip from 209 Crocker Avenue down to Lake Merritt, in the dark of the morning, before the traffic got bad and while the ducks and the police were still half asleep, Lawton, with a friend or two (and Gene tagging along), would put on roller skates and go tearing the mile and a half down Mandana Boulevard, braking by sitting on a broomstick held between the legs. At the bird preserve on the lake, they’d sneak into the bushes, steal the eggs out of the duck nests, put them under their arms to keep them warm, take them home, and put them in an incubator in the basement to hatch them.

They also collected white mice. One day some escaped, and their black and white babies were later found in a woodpile in the basement. They had mated with the wild mice there. One day, when Lawton and Gene walked into the basement playroom, they discovered that the Japanese house boy, perhaps following Roy’s instructions, had built a large fire in the fireplace and thrown in the kids entire three-foot-long cage of white mice. They watched helplessly to their horror as the little pets, with fur ablaze, frantically tried to escape … in vain.

Roy and Hazle’s friends in the neighborhood had few kids that were Lawton’s age. Pat Harrold was the exception; Stanley Dollar was usually away at private school. But they had many friends with kids Gene’s age: Ben Reed, Ed Oliver, Bill Sander, John Richardson, and Dudley Dexter. They organized a club called Lone Star and built a clubhouse in an empty lot, complete with dug-out basement. They held regular meetings, established rules of conduct, put on short plays and magic shows for their families, and organized games and activities. Many of Nancy’s friends’ parents were also friends of Roy and Hazle, who lived in the neighborhood.

About a year after the family moved to Crocker Avenue, Nancy (age six to seven) started school in the first grade at Miss Ransom’s. she continued there until sixth grade in 1931. During her first few years, she met a small circle of close friends, all girls, who became her (and one another’s) lifelong dearest companions: Martha Dexter (Milligan), Jean Campbell (Hanson), Harriet Johnston (Evans), Barbara/Buz Sherwood (Rolph), Shirley Okell (Beedy), and Shirley Makinson (Greig). Until sixth grade, these friends were the center of her world.

On 16 September 1926 Roy’s mother, Charlotte Avery Shurtleff, died at her home in north Berkeley of angina, at age 77. The family drove to her home, and before Roy went in alone, he asked Lawton, as his oldest son (age 12), to please take charge of getting Hazle and the others home safely. Lawton felt he had just become “a man.” Roy later administered the distribution of Charlotte’s estate equally to her four children. At Sunny Hills, the Charlotte Shurtleff Health Cottage was constructed in her memory. Thereafter Roy donated $25 a month, increasing to $35 in the mid-1970s, to Sunny Hills. Roy became Endowment Treasurer for Sunny Hills in 1955, then in 1961 Endowment Chairman. In 1962 he was elected as an Honorary Vice President, and in 1967 Honorary Life Member. Nancy recalls driving to Sunny Hills on quite a few weekends with Roy and sometimes Hazle in the late 1920s. Sunny Hills still existed in 1987, but its activities had changed in the early 1950s with the passage of the Foster Home Care Act, which placed orphans in private homes with foster parents.

After moving to Piedmont, the family continued to spend their summers at Lake Tahoe. In 1926 the two boys spent the summer at Frank Kleeburger’s Talking Mountain Camp on Echo Lake, south of Tahoe.

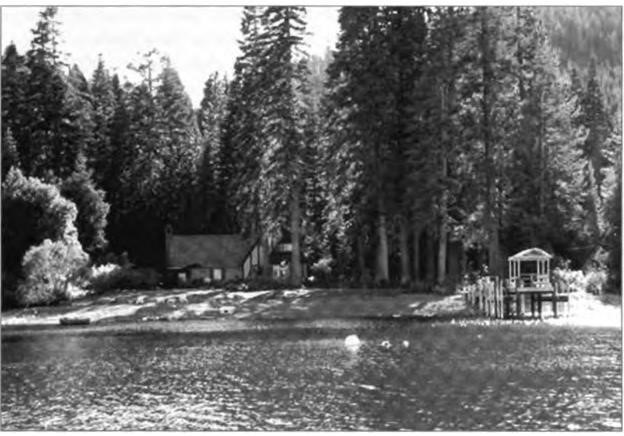

On 31 August 1926 the family bought lakefront property at Homewood by purchasing Lots 72, 73, and 74 of “Lakeside on Lake Tahoe” from Charles S. Cushing and his wife, Anne for $10 in gold coin. The deed was in Hazle’s name. They contracted to have built a one-and-a-half-story house plus (nearby across Madden Creek) a garage-boathouse with servants’ quarters upstairs, all built to their own architect’s plan. Hazle wanted the roof to sag as if it had been bowed under the weight of snow, and to appear uneven in the style of English country cottages. When the roofer had finished trying to fulfill her unusual wish, he said aloud to Hazle: “This is the worst damn job of roofing I have ever done.” He wanted it to be straight and true, reflecting proper craftsmanship. The living room had a massive rock fireplace. A fine pier was built for the boats, complete with a diving board for the many swimmers.

The property at Homewood included two acres of waterfront property on both sides of Madden Creek (which flowed into Lake Tahoe on the property), with two acres directly across the road purchased a year or two later as protection from unwanted buildings on it. These were Lots 131, 132 and 133 across State Highway 89. They still remain undeveloped.

While the house was under construction, Roy camped out with Lawton and Gene (ages 13 and 10 respectively) on the property beside Madden Creek, on the other side of the road. The two boys received training in camping and cooking (baking potatoes in the campfire coals) and helped their father with work around the building site.

Between the house and the lake was a thick bank of willow trees that Hazle liked because they protected the house from noise from the lake. However the willows also blocked any view of the lake from the house—later owners of the house replaced the willows with a large lawn. Near the lake was a full-sized croquet court, not far from a large barbecue pit. Tracks allowed their Garwood speedboat to be pulled up into the boathouse.

A chauffeur lived upstairs over the main house. He could do a trick the kids loved: He would hold out his arm until a mosquito bit it, then he would clench his arm muscles so tightly that the insect could not withdraw its proboscis. Finally he would swat the little critter dead.

As of 1993 this home was beautifully maintained, with a large lawn sloping down toward Lake Tahoe and a lush garden of Tahoe wildflowers along the north side. It is located about 1/2 mile north of Obexer’s and the center of Homewood; the street number is 4090.

The Shurtleffs second boat at Tahoe was the Wee Bit, a neat mahogany hull runabout, about 12 feet long, with an outboard motor mounted inboard as on the Blue Indian. By 1928 they were aquaplaning behind it.

In the summer of 1929 Roy bought a 1928 Model 26-foot-long Garwood speedboat that they named the NANJELAW (an acronym for Nancy, Gene, and Lawton). The boat had been shipped by rail on a flatcar from San Francisco to Tahoe City. A photo (above) from this period shows the boat on its trailer at Obexer’s pier. Jake Obexer, at far right, sold Garwoods and Standard Oil products.

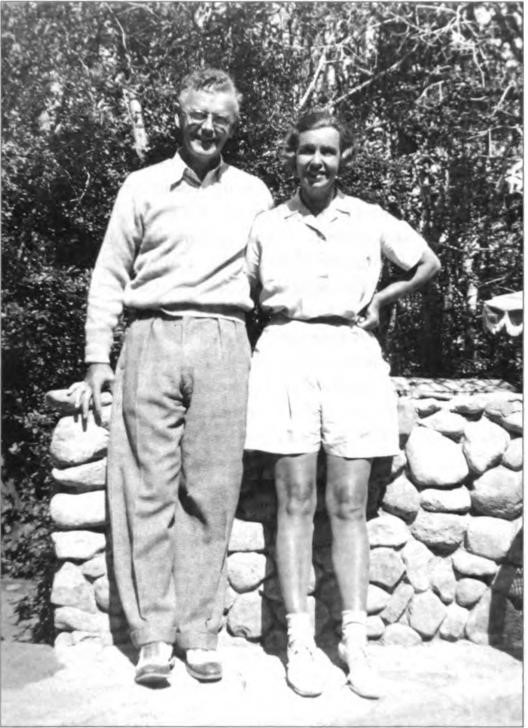

Completion of the house at Homewood in 1927 marked the beginning of an important and happy period for the entire Shurtleff family. For the next nine years, the family enjoyed a three-month summer vacation from June until August, often together with friends of the family and children’s friends who visited for weeks at a time. Roy usually stayed for one full month (August) and came up for weekends during the other months. At the start of each summer, the seven-passenger limousine in Piedmont was packed to the hilt the night before, with luggage piled on the rear rack, running boards, and fenders. Sometimes both family cars were necessary to hold the tons of stuff; from time to time a trailer was added to accommodate all of the luggage and household necessities. A chauffeur would drive one car and Roy would drive his four-door 1929 Packard convertible. All aboard thrilled to hear him say as they set out: “No one will pass me on this trip to Tahoe.” No one ever did. Gene Recalls:

Hazle would blossom in the mountains. The family entertained and had a lot of fun, with beach parties and laughing and singing around the bonfire. One center of activity was a beautiful croquet court. The couple that lived above the garage (Karmi and Sam) helped Hazle in the kitchen and a chauffeur-handyman (James) lived in the attic and helped to maintain the place.

One year, while driving past Emerald Bay in a car pulling a trailer (loaded with a new refrigerator), the trailer’s axle froze and it lost a wheel, which we watched roll down the steep slope. What to do? Roy, traveling with an axe, sent Lawton and me to cut a pine sapling. With rope we tied it on the axle to act as a brace and a sled. When one wore out, we replaced it with another. We finally made it back to Homewood late at night, tired but all intact.

The summers were learning periods, with the family together and sharing experiences. We learned to work, taking on chores of maintaining the grounds and equipment, raking, watering, building, and creating— duplicating the mandated Sunday work from 209 Crocker Ave. Hazle thrived and generated ideas faster than they could be implemented. We learned to play—developing skills at fishing, hiking, and water sports, including small boat racing, aquaplaning, and, of course, swimming and diving. More significantly, we learned to be resourceful, as only the mountains can teach it. We learned to understand and respect the mysteries of nature. We trapped and released chipmunks and minnows. We learned the names and habits of the birds, collecting nests and eggs. We collected, identified, and pressed wild flowers, and became familiar with the native trees and shrubs. All in all we learned to love the Sierra and its beauty with the rivers and lakes. This love later took our families to Echo Lake and was transmitted to the next generations.

Lawton recalls that in those days the lake was much clearer than 60 years later. One could read a newspaper headline in 40 feet of water. Suckers and chubs were numerous around the piers; by the mid-1980s there were few or none.

In about 1927, in the winter, Hazle had major surgery, a hysterectomy, in New York City. While she and Roy were away, grandparents Frank and Fannie Lawton (and perhaps Aunt Dorothy Peet) stayed with the kids, who sent letters and photos. Gene, who was in Boy Pioneers (predecessor to Cub Scouts), recalls Fannie Lawton rushing him to have a photo taken with his Boy Pioneer award stripes on so that it could be mailed to New York to arrive by the time Hazle came out of surgery. After returning home to Piedmont, she was in bed for a month or two recovering, cared for by Miss Ruth Reeder, a registered nurse. Hazle never discussed this operation with Nancy.

But Hazle continued to have health problems. In 1927 or 1928 a Dr. Strietman diagnosed her condition as colitis (inflammation of the colon). According to Nancy this inflammation, accompanied by indigestion and fatigue, would plague Hazle almost constantly until the end of her days. Yet until the mid- to late 1930s Hazle led an extremely active life, having to go to bed only occasionally for short periods of time. She would entertain extensively in Piedmont, invite many family friends and the kids’ friends to Tahoe, ride horseback, swim, play golf, work hard in her garden, and drive to visit her kids when they were away at boarding school on the weekends.

Hazle and Roy wanted the best possible education for their children. So in about 1924-28 they brought in French, piano, and even boxing instructors. The French tutor taught all three kids for an hour one day a week, then stayed for a dinner where only French was spoken. This went on for about six months. All three also took piano lessons from Miss Harriet Hundley for two or three years and she pasted colored stars for each child after each lesson to rate their performance. Alas, not one child ever learned to speak French or play the piano. The boxing lessons, as one might have expected, were more fruitful. Lawton boxed in college with his fraternity brothers and also taught a little boxing to his own sons.

Although Gene became a good athlete in high school and college, he was not always that way. Prior to high school, as noted earlier, he had poor physical coordination. Hazle took a deep interest in this matter and, when he was in fourth grade (about 10-11 years old), founded a “Eurhythmics” class, which taught physical coordination to 30-40 children at the nearby Piedmont Community Center in the big Piedmont Community Hall, off Highland Avenue. An excellent woman instructor there who played the piano while the kids walked around the room, sometimes on tiptoes, sometimes skipping, sometimes rubbing the head and patting the stomach to improve coordination. Six to twelve months at this class helped Gene’s coordination and confidence so much that Nancy also eventually went.

As he was getting over his uncoordination problem, Gene was hit by yet another one: hay fever. It started in the late 1920s at about the time he entered high school. Roy and Hazle sent him to the famous allergist, Dr. Albert Rowe, Sr., who found from tests that Gene was allergic to 50 or 60 things including ordinary house dust, dog and cat fur, and the like. He inoculated Gene with these substances, and very slowly he became immunized. But throughout high school and into his college years Gene’s hay fever was a major irritant and adversary. When attacks occurred, it was like having a bad cold plus sinus congestion with excessive sneezing, runny eyes, and an itchy roof of the mouth. The general discomfort hurt his studies and left him feeling drained.

Nancy recalls that Roy and Hazle were the kind of people that other people (including kids) liked to be around. “Our house at 209 Crocker Avenue was very much a gathering spot for kids. Every morning our dining room was full of kids waiting around the side of the room for us to finish breakfast. Then we’d all walk or bike to school together. After school we’d all come back and gather in the pool room to play pool. Lawton’s friends like Pat Harrold would also come by.” Roy further helped make the Shurtleff house a center of recreation for the neighborhood kids by building the basement game room and a basketball hoop over the garage door, where they would shoot baskets by the hour.

After their sons left Montezuma, Roy and Hazle had hoped to be able to send them directly to an aristocratic and excellent preparatory private boys boarding school in San Rafael named Tamalpais School. But Tamalpais required at least one year of Latin (which was not taught in public schools at the time) as a prerequisite for admission. So in September 1927 they were both enrolled for a year at Miss Wallace’s school in the Piedmont hills. Miss Wallace was a teacher with modern ideas. Some of the classes were held out-of-doors. The kids studied Latin, played tennis, and learned how to pass an entrance exam. A year later, in the fall of 1928, they were admitted to Tamalpais; Gene repeated seventh grade and Lawton started as a freshman.

On 21 July 1929 Red Crown Gasoline sponsored the Lake Tahoe Power Boat Races. The winners were announced in the Los Angeles Times. The Nanjelaw, owned by Roy Shurtleff, won third place in Class 4-150 horsepower displacement.

Blyth, Witter & Co. prospered in the euphoric economic climate of the late 1920s. In 1925-26 the firm financed the construction of the 30-story Russ Building in San Francisco. Offices were moved from the Merchant’s Exchange Building to the twenty-first floor of the Russ Building as soon as it was completed, and there they remained until 1968. In 1928 Blyth decided to enter the brokerage business and to purchase a seat on the New York Stock Exchange (a move which later proved to be very poorly timed). On 1 January 1929 the firm changed its name from Blyth, Witter & Co. to Blyth & Co. and began its brokerage work. Roy’s duties and responsibilities expanded from mainly sales to include new underwriting business and administrative work.

The Wall Street Journal broke the story on 12 December 1928 under “New Partnerships” (p. 5). It was first time Blyth & Co. had ever been mentioned in that prestigious newspaper. Two major follow-up articles followed in the Journal: “To Succeed Blyth, Witter” (December 19, p. 38) and “Blyth Copartnership Succeeds Blyth-Witter: Banking House to Broaden Its Scope, as Blyth & Co. Become Members of Stock Exchange” (December 20, p. 6).

By 1929 the Shurtleff family was doing well by any standards. Looking back from 1984 Gene Shurtleff summarized the period:

The young man who had been raised as a poor boy, with no father but with a frugal and ambitious mother, now at age 42 had made his first million dollars (based largely on his ownership of Blyth stock) and become the head of a family living in the lap of luxury. Nothing seemed impossible. They owned a lovely home in Piedmont in a neighborhood with many wealthy friends. Their house was staffed with servants so that they could entertain in a lavish style. They were members of the socially prominent Claremont Country Club, kept three saddle horses at the Piedmont Trail Club for the family’s horseback riding, and owned a summer home at Lake Tahoe. Roy belonged to the Bohemian Club in San Francisco and Hazle was a member of the fashionable Woman’s Athletic Club in Oakland. At the 1929 automobile show in San Francisco Roy had purchased a stylish seven-passenger Cadillac limousine and a very sporty two-tone brown and tan four-door Packard convertible with synchromesh (silent shifting) gears. The three children were being educated in the finest private schools in northern California. Business was in a boom phase with the stock market and Blyth’s profitability at record highs. Roy negotiated a substantial loan with the Wells Fargo Bank to increase his investment in Blyth to equal that of George Leib.

The United States and many nations around the world were enjoying a period of phenomenal expansion. “Prosperity” was the new buzzword and Wall Street, with unrestrained optimism, thought that prosperity would last for ever. The secret to meeting human needs had been discovered. Science and invention would allow fulfillment of the world’s future dreams.

The capitalist economic system, a fragile interlocking of complex mechanisms, contained unexpected perfections and obscure but severe weaknesses in its very foundations.

In the presidential election of 1928 Republican Herbert Hoover defeated Governor Alfred E. Smith in a landslide victory (444 to 87 electoral votes). Hoover was inaugurated in March of 1929 with the stock market rising daily to new and dizzying heights.

Despite the contagious and buoyant optimism of the period, some more cautious businessmen felt a sense of uneasiness. Roy was one of these. A favorite saying of his at the time was, “No tree grows to the moon.” In a tour of the Blyth offices in 1929, Roy carefully checked the inventory that each was carrying. He grew concerned over the many speculative and low-quality securities and accounts, and immediately, though the market was booming, ordered a massive house cleaning that liquidated $7 million of marginal accounts. In The Blyth Story, Soher (1964) noted: “This action, for which Roy Shurtleff alone was responsible, was one of the most important single decisions in the history of the firm. If Roy had done nothing else in his entire career, the organization would have been most grateful for his action. It presumably made the difference between survival and extinction.”