** All Text on these chapter pages has been copied verbatim – with permission – from this book: “Shurtleff Family Genealogy & History – Second Edition 2005” by William Roy Shurtleff & his dad, Lawton Lothrop Shurtleff ** Text in pdf convert to word doc – any spelling errors from the book may or may not have been fixed. **

In about 1921 the family moved to 372 Euclid Avenue, an upper-middle-class neighborhood in Oakland, just a few hundred yards from Lake Merritt. Lawton, now about seven years old, started kindergarten at Lakeview Grammer School, while the family was still quite involved with Christian Science and its methods of healing by faith.

Lawton’s earliest recollections of Hazle being ill are from this house. She began to spend quite a bit of time in bed but the cause of her illness was then unknown. Lawton remembers Hazle often being in bed when Roy would come up the road whistling to her as he returned from work. Roy would take the streetcar on Lakeshore to Euclid Avenue, then walk home. The children would often run down to the corner to walk with him. Roy was a good whistler. He had a tremendously loud finger whistle, and a sweet whistle that was his special little call to Hazle.

At Euclid Avenue the family had first begun to have a full-time governess (a nanny or nurse), mainly to help Hazle in raising the kids, even though the Shurtleffs were not wealthy. Most other families in the area had no such help. Hazle was not yet under the care of a nurse, but she needed help with the kids. The first governess was Mrs. Carse, who spoke with a strong Scottish brogue. Then came Fraulein (pronounced FRAU-line), a German girl about 21 years old. The kids remember how the nurse would walk them down to Lake Merritt to watch the ducks. The first cook was deaf old Maggie.

During these years Roy often referred to Lawton as “Sunny Jim,” and Lawton and Gene called their parents “Daddy Man” and “Mother Dear.” This had stopped by the time Lawton reached high school, but Hazle once remarked later how she missed these “good old names.”

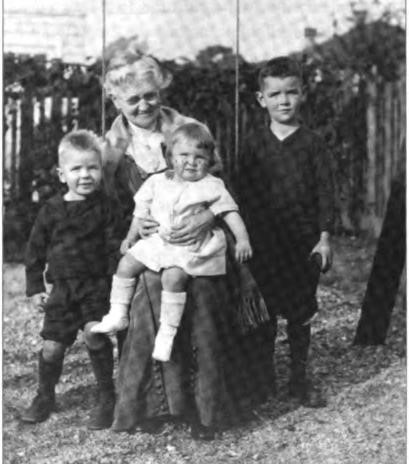

Charlotte Avery Shurtleff frequently visited Roy and Hazle’s family at Euclid Avenue. She adored her three grandchildren, who called her “Daddy’s Namu,” or less commonly “Grandma” or “Grandmama.” On her visits she always brought licorice candy, and frequently gifts of her hand-knitted woolen sweaters and socks. A photograph from 1921 shows her playing with her grandchildren on a swing at Euclid Avenue.

Shortly after their move to Euclid, the Shurtleffs joined their first social club, the Sequoia Country Club, off Montclair in the Oakland hills. (It was still there in 1987). Sequoia was primarily a golf club, with its own course, and Roy began to play there with his friends. The family occasionally dined in the clubhouse.

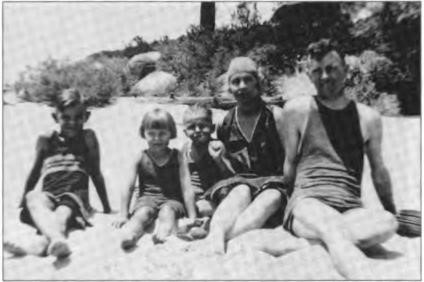

Grandmother Shurtleff (Charlotte Avery) at Euclid Avenue with her Shurtleff grandchildren in 1921. She also had four grandchildren from her first marriage to John David Meek. (L-R) Gene, Nancy, and Lawton.

In about 1923 Roy and Hazle took the three kids out of school in Oakland and moved to a small, gray-shingled summer house they rented from Paul (“Pearly”) Brown, at the base of Mt. Diablo near a deep creek. The main reason for the move was to give the children an experience of country life. Lawton and Gene attended the one-room Green Valley School on the road to Danville, commuting the mile or so by car or occasionally by horse and buggy. Roy stayed at the Euclid Avenue house during the week, then commuted on weekends from San Francisco to Berkeley. There he caught the San Francisco-Sacramento Short Line train, which wound its way from Oakland through a tunnel in the Coast Range into Shepherd Canyon, along Pinehurst Road and San Leandro Creek, through Canyon and Moraga, past St. Mary’s College, into Lafayette, and finally out to Diablo, where he joined the rest of the family.

The family left the Sequoia Country Club and joined the more prestigious Diablo Country Club, where Roy continued his golf. He found the game as frustrating as it was relaxing or challenging, and it was in connection with golf that the kids first remember hearing him swear (which he almost never did) when he mumbled something about “not a hell of a good game.” At the foot of the great mountain the children first learned to swim, hike, and enjoy the out-of-doors. Diablo, along with Neptune Beach in Alameda, was one of the few swimming areas in the East Bay. There were few private pools. Though the Diablo Lake was the center of social life and swimming, the club later also had a large concrete swimming pool, which was less popular. Roy sometimes took Lawton and Gene fishing for perch and bass in the Diablo Lake. Lawton worked in the stables and milked the cows. Roy and Hazle would sometimes rent a horse and buggy for the family or kids. Gene recalls that one time the horse ran away with the buggy, flipped it, and threw him out. The family went to Diablo probably for two summers, in 1923 and 1924, and part or all of that school year. Mrs. Carse accompanied them as governess.

At Euclid Avenue Hazle built a solarium with a fountain, surrounded by live ferns that the family collected in Monte Rio. The home was so attractive that Hazle’s brother Don Lawton (and his bride Billie Spaulding) and her sister Dorothy Lawton (and her groom Harry Peet) were married there. The house is no longer standing; in the early 1960s it was torn down and a four-story high-rise apartment built in its place.

On 14 June 1923 Harry Lawton, Hazle’s older brother, married Beatrice Joyce Birbeck at her mother’s home in Piedmont, California. Harry had a lot of friends by that time, but nevertheless he chose Roy Shurtleff to be the best man at his wedding. That was a real tribute to Roy and to their strong friendship.

During the 1920s Blyth grew proportionally faster and achieved more than in any other decade in its history. It expanded from a basically local securities company to a nationally known investment house doing a considerable volume of business. Many new offices were opened, including one in Chicago in 1922. Blyth provided the original financing for the Caterpillar Tractor Co.

On 5 February 1924, as a symbol of his and Blyth’s growing success, Roy first became a member of the prestigious Pacific Union Club in San Francisco in the old Flood estate atop Nob Hill.

In 1924, after a disagreement with Charlie Blyth concerning the desirability of continuing the East Coast offices, Dean Witter left the company to form his own firm, Dean Witter & Co. His Blyth stock was sold back to the company, and purchased by remaining shareholders. He took with him his brother, his cousin (Jean Witter), and a few others. The two organizations have since remained friendly competitors. Although Charlie Blyth and Dean Witter were never close friends after the separation, Roy and Dean continued their long-standing friendship.

In 1925 Blyth opened its first overseas office in London. Also in 1925 Blyth, with Roy in charge of the project, played a major and creative role in financing construction of the Carquinez Bridge, one of the first bridges in the Bay Area (along with the Dumbarton). Roy’s director fees were paid in gold coins. Roy’s sister, Nettie, was also part of the project, in the sense that she was the secretary, at Cal, for Charles Derleth, who designed the Carquinez, Antioch, and Golden Gate Bridges. In the mid-1930s, Blyth played a major role in funding the Golden Gate Bridge.

On 17 September 1923, on a dry fall day, there was a huge fire in Berkeley. It was started by a broken electric wire high in the hills to the north near Wildcat Canyon. The fire, whipped by a hot north wind from the hills and fed by wood shingle roofs, roared through the neighborhoods north of the Berkeley campus, destroying 584 homes (plus 16 other buildings) in two hours and leaving 4,000 people homeless. It was finally stopped on the northern edge of the campus. As of 1991, it was California’s most destructive wildfire in a settled area.

Roy, at work in San Francisco, called Hazle, who took Gene and Nancy and the dog in her car to pack up Roy’s mother, Charlotte, at her house on Hearst Avenue at Oxford. Charlotte and Nettie had managed to save a few valuable possessions from the flaming building, but shortly thereafter the house burned to the ground. Being located on the northwest corner of campus, it was one of the last to burn before the fire was halted. The family Bible, containing many vital statistics and genealogical records, was destroyed by the fire. Charlotte later relocated in north Berkeley, but the shock of losing her home was too much for her, and Nettie considered it the main cause of her death three years later. Charlotte had owned the land on which her house stood, and apparently after the fire she gave or sold it equally to her four children, for in May 1927 Roy and Hazle gave their one-quarter portion of the land to Nettie and Jessie Meek.

In 1925 Roy and Hazle’s family first began to spend their summers at Lake Tahoe, then billed as “California’s Popular Mountain Resort.” Roads had followed the train lines in opening this beautiful part of the Sierra Nevada to the Bay Area public. For two or three summers the Shurtleffs stayed at a cabin connected with the Brockway Hotel and Hot Springs (commonly called the Brockway Resort). Harry Comstock planned to turn Brockway into a private club and Roy went up initially to take an option on membership. Lawton and Hazle were the first to swim in its new pool. The once-famous hot springs were by then dilapidated; only a decaying breakwater remained. The long colorful steamer, the S.S. Tahoe, and the smaller Nevada, could be seen circling the lake. The Tahoe delivered the mail and food to resorts around the lake.

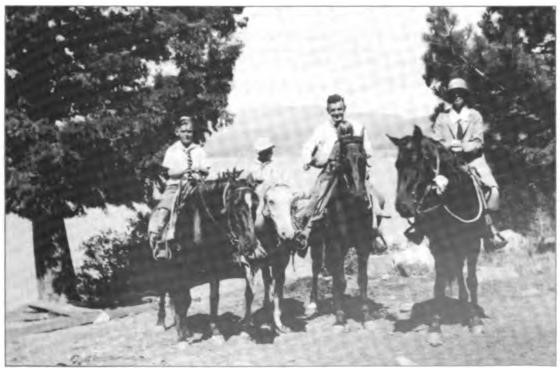

It was at Brockway that the family began to ride horses. Gladys Comstock, the attractive stable girl who was also Harry Comstock’s daughter, used to lead children’s rides, sometimes by moonlight, on Tenderfoot Mountain behind Brockway. Lawton remembers this because he had “kind of a crush on Gladys,” who was seven or eight years older than he. He and Gene rode a little white horse named Nevada. The family rode horses owned by the resort. Roy held Nancy in his lap.

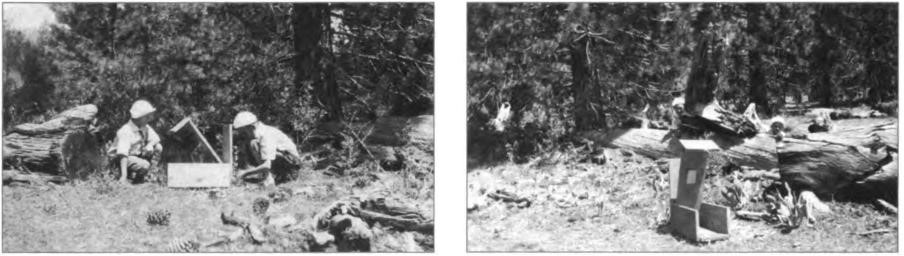

Also at Brockway Lawton and Gene spent hours building ingenious, self-designed chipmunk traps. They worked, and the prey, turned pets, were kept in cages, then set free at the end of summer. The kids tried bringing their pets home to the Bay Area several times, but they never lived at low altitudes.

Roy often returned to work in San Francisco during the week while Hazle and the kids stayed up at Brockway. On the weekends, Roy would generally go up to Tahoe by train. He’d board the special Tahoe car at the Oakland Mole on the transcontinental train bound for New York. Many passengers stayed up all night, drinking and talking. When the train stopped in Truckee, arriving about 6 o’clock in the morning, that car was detached, then pushed slowly by another locomotive on a narrow-gauge railway, up the Truckee River to the Tahoe Tavern. In those days, the tavern, along with Glenbrook at Brockway, was one of the two largest and most famous resorts at Tahoe. Remarkably, the car was pushed out onto the Tahoe Tavern pier. Hazle and the children got up in the dark to drive their automobile north over the mountains to Truckee or to the Tahoe Tavern to pick up Roy.

At the beginning of each summer, the family drove their automobile to Tahoe; the grueling (though sometimes exciting) trip took at least eight hours. They often spent the night in Sacramento, Colfax, or Placerville. Though most lowland roads were paved, those in the mountains were mostly gravel, dirt, or mud, and the spindly bridges were one-way.

The family’s first boat was the Blue Indian, purchased in 1925 when the family was at Brockway. An oversized pontoon canoe with a big one- or two-cylinder outboard engine installed inboard, it was fitted with a convertible canvas top and side curtains. It had been owned by the famous Tahoe lumber tycoon, Mr. Hobart. There was a story that the steering cable had snapped and put out his eye, after which he had decided to sell the canoe. In those days at Brockway there was still commercial fishing.

The children enjoyed boating with a man whose name is remembered as either “Molly” or “Froggy,” who sold his large (15-30 pound) mackinaw trout (also called “lake trout”) to the Brockway Hotel. He often helped the kids crank-start the Blue Indian, a task requiring more muscle than they then had. At about six to seven knots top speed, the Blue Indian was said to be the fastest outboard at that end of the lake. The kids enjoyed driving the Blue Indian in races starting from the Brockway pier then around the large marker buoy, a half mile away, that guided the steamer Tahoe off the rocks in front of Buck’s Beach.

Although Roy and Hazle’s children eventually grew up to be fairly respectable, decent human beings, leaders in their fields and communities, model parents, etc., they were not always that way.

(pictured – Left to right: Lawton, Nancy, Gene, Hazle and Roy on the beach at Brockway where, in summer, the temperature of the icey water rarely exceeded 65’F., circa 1926.)

Lawton is remembered as a generally mischievous, sometimes incorrigible, little rascal. Being the oldest and prime instigator, he often insidiously drew his still innocent siblings into a juvenile life of petty crime and hell raising. Of course, in these formative years at Euclid Avenue, like most children, the Shurtleff kids learned to climb trees, build tree houses, and play in what they called “the mud yard.” But they didn’t stop there. A few examples of what they did and the kind of youngsters they hung out with, may delight their descendants, just as it frazzled their parents.

There were a lot of bad kids in the Euclid Avenue part of Oakland, even though it was basically an upper-middle-class neighborhood. It was very important to be tough and to fistfight well. How could one ever forget the likes of Joe Phinelli (who even as a kid had hair on his chest); “Joe Phinelli had a pimple on his belly / And when he laughed it shook like jelly.” Then there was Frank Bowles, and of course the notorious little brawler Dick Tatterson. Tatterson was later described by Lawton in his journal as “one of the forbidden children, the fellow so seldom seen, with the crayon and given to writing smutty verse on secret walls.” He was also infamous for unbuttoning his pants when anyone would look.

Petty theft is a good way for a kid to start to make his mark in the world. As Lawton recalls: “We used to crawl through our back fence at Euclid Avenue right into the Lakeview Junior High School playground, where I went to school in Oakland. A few friends and I, age 10, had a sophisticated ring that we would use to jimmy open the school windows. Our big thrill was to steal gum erasers and pencil sharpeners.”

Gene is remembered by many as “a very good little boy, a sweet child, and certainly the most well-behaved of the three.” But what he lacked in mischievousness, he made up for in ineptness. For example, one day Roy and Hazle gave the kids a rabbit named Floppy Ears. They raised it for a while and then, for some unknown reason, it died. They buried it and planted a sunflower on the grave. Young Gene was puzzled, and curious apparently about dying. So he innocently took the children’s little dog up to his room in the second story of the family’s two story house and dropped it off “to see what would happen.” They buried it next to the rabbit. Gene admits: “I’ve never been very proud of that story.”

Gene developed a pronounced lisp when he learned to talk. His parents had to send him to a private speech impediment school, where a therapist worked with him, one on one, for about a year during his early grammar school years. By about fourth grade he had conquered his problem. Roy, who had his own speech problem, must have felt deeply for little Gene. And as if all that wasn’t enough, Gene was poorly coordinated as a child. As Lawton, never one to exaggerate, recalls nostalgically:

He could hardly walk across the room without falling down. You’d throw a football at him and it would hit him in the head. He was completely uncoordinated, in fact a pretty helpless, hopeless little kid. But at the same time he was very funny, with a great sense of humor. He was also amazingly fearless. I remember him being teased quite a bit by his peers and slightly older fellows. Gene wouldn’t stand for it. He would get into a fistfight with some kid twice his size. He’s still like that today. He later became a pole vaulting champion at Piedmont High School.

The kids loved to tease Maggie, the old deaf Irish cook at Euclid Avenue, who sometimes doubled as a nurse. They would walk up behind her and whack her on the back to get her attention, or throw coal soot from the furnace room on newly washed sheets she had hung out to dry. That is the end of stories about the children. It would be a few more years until Nancy was old enough to show her true character.

At Euclid Avenue Roy and Hazle felt the need to start teaching the children some discipline. Central to the system they developed was “the book,” a blue book with a printed listing of 10-15 questions to be formally answered concerning the conduct of each child. These included such things as “(1) Played with forbidden children (such as dirty Dick Tatterson); (2) Used bad or nasty language; (3) Talked back…” Each day the reports were formally reviewed and the appropriate punishment delivered, with a razor strap or belt when warranted—which was not infrequently. Lawton recalls that there were no rewards for good behavior, only penalties for bad behavior.

One reason for use of the book was that Hazle, who was often in bed, was unable to care for the children’s discipline herself. When Roy and Hazle were away from home, the governess or sitter in charge was given charge of administering Roy’s reform book. (In later years, while raising his own family, Lawton used a modified form of this system with both financial rewards and punishments. Gene tried it briefly, but the children didn’t respond, so it was short-lived).

In October 1924 Roy and Hazle took a trip, probably about one month long, to New York City. Its purpose is not known. It was probably a business trip, since Blyth & Co. held its annual meeting in New York each November. Dorothy and Harry Peet came from their home at Orange Grove, near Fresno, to stay at Euclid Avenue with the Shurtleff children. Lawton wrote his parents two letters dated October 19 and 30. From these we learn that the children stayed out of school to see the circus; a grading system of “blue birds” and “brownies” (merits and demerits) were being used with the blue book system of discipline; Lawton was taking music lessons (piano) from a teacher (Harriet Hundley, the sister of Helen Lawton’s closest friend), was collecting agates and marbles, and soon would have 500. His parents were staying in a large building in New York shown on a postcard they sent him.

At Euclid Avenue, Lawton and Gene, like many of their friends, built “skate coasters,” forerunners to the popular commercial skateboards of the 1980s. They cut a two-by-four three to four feet long, attached one metal roller skate to the bottom at each end, nailed a three-foot-high wooden apple box to the front, then put wooden handlebars across the top of the box. Pushing with one foot, as on a scooter, they would ride down the gently sloping Euclid Avenue to Lake Merritt and to school.

In these years when the kids were young, Roy did a lot of things with them on weekends or holidays. For example, he went with them to Trestle Glen, a nearby wild canyon, to collect salamanders, frogs’ eggs, pollywogs, and the like. Lawton shot his BB gun at quail. Lawton recalls that it was at about this time that Nancy inadvertently gave him the nickname, “Lawky,” one that stayed with him throughout life. He also remembers how Nancy liked to repeat the rhyme: “Joe, Joe broke his toe/Riding on a bussalo.” That “Joe” referred to Joe Bowles, son of the neighborhood doctor.