** All Text on these chapter pages has been copied verbatim – with permission – from this book: “Shurtleff Family Genealogy & History – Second Edition 2005” by William Roy Shurtleff & his dad, Lawton Lothrop Shurtleff ** Text in pdf convert to word doc – any spelling errors from the book may or may not have been fixed. **

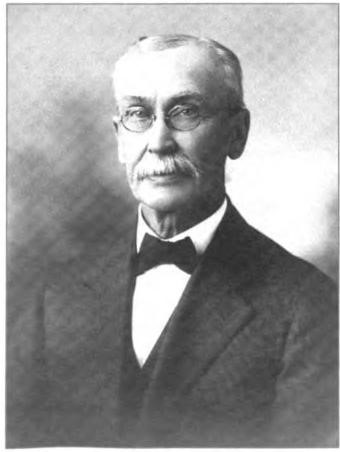

Early Years (1852-83). Frank and Fannie were Hazle Clifton Lawton’s parents. Frank was born on 28 December 1852 in Clyde, Wayne County, New York, the youngest of eight boys. Birnelyn Seymour Piper, his granddaughter, believes that all of his brothers were professional men. His father was Charles D. Lawton, born in Newport, Rhode Island, on 17 September 1802. His mother was Susan A. Houghteling, born in Susquehanna, Chenango County, New York on 30 March 1812.

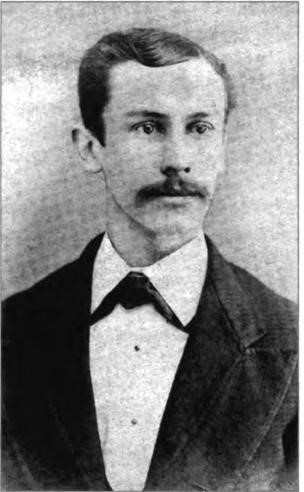

The 1870 U.S. Census shows Frank to be 17 years old and living with his parents in Clyde, New York. Photographs taken in 1872 show him to still be residing in Clyde. It was at about this time that Frank suffered a severe accident. He was driving a big, flatbed Studebaker wagon, pulled by a team of horses. Suddenly the horses began to run out of control. When he stood up to try to rein them in, he fell off and the heavy wagon wheel ran over one of his feet and crushed it. As his son Don recalls:

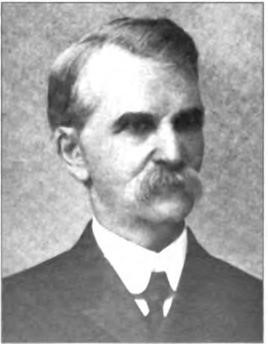

Pictured – Young Frank H. Lawton, soon to be patriarch of the Lawton family line, circa 1872.

The doctor said, “Now listen. I can take off this foot, since it is crushed beyond repair, and I’ll have you out of bed in 6 to 8 weeks.” Frank replied, “Well, so what i f I don’t?” The doctor warned, “You might be in bed for a year or two.” Frank said firmly, “That foot doesn’t come off” So he stayed in bed for a year rather than have it amputated. For the rest of his life, he walked with a slight limp and had to wear high black lace-up boots to support his weak foot.

Neither Frank nor his parents are shown as being in Clyde on the 1875 state census. Birnelyn Seymour Piper recalls hearing from her mother, Winnie, that Frank’s father, Charles, had signed as guarantor for a large loan or debt on behalf of a friend. The friend was never able to pay. Charles could have gotten out of his obligation, but he was a man of such high principles that he paid the debt. Because of this, there was no money left for his youngest son, Frank, to go to college. Instead, young Frank worked in a drugstore for a while and thought seriously about becoming a doctor. Then he decided that he would like to go out West, start a new life, and go into business. Although he never did go to college, he was a very well-educated man. He read and studied a great deal.

His elder brother, William D. Lawton, had gone to San Francisco, California, arriving in about 1874. After working as a salesman for Percy Beamish, an importer and manufacturer of shirts and other clothing, he started his own business, W. D. Lawton & Co., in about 1876 at 9 Post Street and 608 Market Street It manufactured fine men’s shirts and collars. He may have started with a partner, B. F. Commings. So, in the late 1870s Frank Lawton left Clyde, New York, and headed west.

Starting in about the mid-1800s, long before the telephone was invented, many larger cities had a book called a City Directory. Similar in conception to today’s phone book, it listed the name, home and business address, and usually the occupation for most heads of households in the city.

The San Francisco City Directory for 1879-80 (when he was about 27 years old) first lists him as a shirtmaker residing at 417 Mason Street. The next Directory shows him to be working as a bookkeeper for his brother at W. D. Lawton & Co. and living with his brother at 1718 Turk Street.

It is not clear when or how Frank Lawton met his bride to be, Francis Marion Rogers. She was living in San Francisco from 1877 on and working as a clothing saleslady and then as a milliner, so they may have met on business. They were married on 17 May 1884 in San Francisco by the Rev. Robert Patterson. The place of the marriage and their religious affiliations are not known. He was 31 years old, and she was 24. Frank was about 6 feet 4 inches tall, and lean and serious. Fannie was no bigger than a minute, and no taller than 4 feet 11 inches, but full of spirit and fun and love. Frank’s growing shirt business supported the young couple quite adequately.

Fannie Rogers and Her Ancestors. Fannie’s parents pose an intriguing mystery in our family history. Despite years of intensive genealogical research, there are still important gaps in our knowledge; yet we do know quite a bit about them. Her father was almost certainly William P. Rogers, who was born in about 1810 in Maryland, probably in Baltimore. We do not know the names of his parents. We are quite sure that William had a younger brother, Thomas Rogers, who was also born in Maryland, in about 1812-20.

Fannie’s mother was almost certainly Frances O’Donnell, who was born in about 1824-25 in Maryland, probably in Baltimore. We are almost certain of her maiden name, but we do not know the names of her parents or of any of her siblings—if she had any.

A marriage record shows that William Rogers and “Francis Odonnell” were married on 11 August 1840 at St. Mary’s Church (Roman Catholic), Chartres Street, New Orleans. The names of their parents are not given—and we have never been able to find them. The Rev. Constantine Maenhaut, Rector, officiated, in the presence of Charles Hefferman, Eva Jackson, and Thomas Rogers (probably William’s brother), witnesses.

Note that Frances (the bride) was about 15-16 years old at the time and William about 30, or 14-15 years older. Since Frances was so young, and since she was married by a Catholic priest, why were her parents not present to give permission and serve as witnesses? We are almost sure that William was a sea captain and that his bride’s first name was spelled “Frances.” Unfortunately, we do not know the name of his ship. He probably sailed from Maryland to Louisiana. Yet it is not clear why he and Frances chose to live in Louisiana.

In about June 1846, William Henry Rogers was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, the first known child of William and Frances Rogers. We have been unable to find this birth certificate; this information comes from William Henry’s death certificate (in 1864, at age 17).

In 1848 in New Orleans Mrs. Frances Rogers purchased a slave from Walter Lewis Campbell, according to the Notorial Records of Edward Barnett (vol. 46, p. 60).

On 25 January 1850 William Rogers purchased a “negress slave Acerlane,” aged 21-22 from Claire Panche, “fully guaranteed against the vices and maladies prescribed by the law except the vice of running away.” On the deed of sale are the signatures of Wm. Rogers, Selim Wagner, Alphonse Charles Weysham, and perhaps an O’Donnell. Note that this took place more than a decade before the start of the Civil War.

The New Orleans City Directory for 1850 shows a Captain William Rogers (probably ours) residing at 13 Victoria Street (presently known as Decatur Street).

On 23 February 1850, Frances Rogers sold the female slave she had purchased only a month earlier. William appeared before notary Edward Barnett in New Orleans and “declared that he does and by these presents appoint and, in his place, and stead put his wife Mistress Frances O’Donnell to be his true and faithful attorney… to sell a Negro slave named Acerlane” notarized by Barnett on January 25. The same four signatures appear, including a clear signature of “William Rogers” (see vol. 52, p. 122). The sale of the slave was finalized on May 7—according to conveyance records.

The book San Francisco Passenger Lists, Vol. 1 1850-1875, by Rasmussen contains an entry (p. 14) that seems to fit well with the movements of our Rogers family: The ship California (Capt: Lt. T. A. Budd), a steamer from Panama, arrived in San Francisco on 25 March 1850. One of the many passengers was Mrs. F. O’Donnell. The trip from Panama took 23 days. Yet if this was our Frances, why did she give her surname as “O’Donnell” rather than “Rogers”? Very few women joined the Gold Rush to California—only about 10-15 percent of those who rushed in. Therefore, it seems highly unlikely that more than one woman with this name would be arriving in San Francisco at about this time.

Let us propose a theory to explain many of these unusual events. In late 1849 or early 1850 William Rogers received news from this brother, Thomas (who was in San Francisco), that he should come quickly to join the California Gold Rush. In about February 1850, William hastily sailed from New Orleans, around Cape Horn, to San Francisco, leaving his business-oriented wife to clear up the sale of the female slave, Acerlane, that he had purchased only a month before; California was a “free” state and slavery was against the law. After Francis settled the family’s affairs in New Orleans, she and her young son, William about age four, left immediately, crossed the Isthmus of Panama, then traveled by steamer to meet her husband in San Francisco.

Pioneers in San Francisco. Both William and Thomas Rogers were in San Francisco, California by September 1850. The “Society of California Pioneers Centennial Roster, Commemorative Edition,” edited by Walter C. Allen and published on 1 May 1948 shows that a Thomas Rogers (almost certainly ours) arrived in San Francisco on 8 November 1849, and was an early member of the society, which was founded in 1850.

These were heady days in San Francisco. Only a few years previously (on 30 January 1847) the city had changed its name from Yerba Buena to San Francisco, to tie it with the bay, named San Francisco Bay since an earlier date. The discovery of gold at Sutter’s mill on 24 January 1848 had led to the Gold Rush of 1849, flooding the city with new inhabitants. On 9 September 1850 California became the 31st state to enter the union.

Kimball’s San Francisco City Directory for 1850 listed William Rogers as a harbor pilot, working out of the Harbor Master’s Office. He was one of only four harbor pilots listed in San Francisco at the time. Thomas Rogers was listed as a laborer, living on Ohio Street, between Broadway and Pacific.

It is not clear where William was living in 1850. It seems most likely from the City Directory listing that he was either living at the Harbor Master’s office or with his brother, Thomas. Neither of these places was near Nob Hill.

By 8 November 1853 William and Thomas had begun to buy land in Alameda County, across the San Francisco Bay. The Alameda County Deed Book B (p. 272) shows that they jointly purchased Block 25 on Kellersberger’s Survey, part of Rancho Todos Santos, for $1,200. A map of the Oakland-Berkeley area surveyed by Julius Kellersberger in 1857, titled “Map of the Ranchos of Vincente and Domingo Peralta,” shows most of Alameda County divided into blocks averaging about 640 acres, and each block divided into various lots. Though no reference to the term “Ranchos Todos Santos” or “Rancho of Todos Santos” in Alameda County can be found, it appears repeatedly in subsequent land deeds related to this piece of land. On the Peralta map of 1857, Block 25 is located just to the northeast of the northeast tip of what is now called Lake Merritt.

This piece of land changed hands within the family numerous times. In February 1855 William Rogers (“of Alameda County”) sold his portion of the land to Thomas Rogers (“of San Francisco”) for $4,000. It seems strange that he would have made such a huge profit after only two years. Then a year later Thomas sold Frances all or part of his share of Block 25 for only $1. No explanation for these unusual transactions is given in the deeds of sale. In the Alameda County deed books, some 33 land transactions are recorded from 1853 to 1873 in which either William, Frances, or Thomas was a buyer or seller. The land, which was in what are today the cities of Oakland, Alameda, San Leandro, and probably Berkeley, was usually paid for in United States gold coin. A number of fairly large loans were negotiated to buy some of this land. The source of these loans is not given on the deeds.

The 1854 San Francisco City Directory reveals three interesting changes: First, Thomas’s occupation has changed from laborer to pilot. Second, William’s occupation has changed from harbor pilot to sea captain. And third, Thomas was now living in the same house as William and his family at the northwest corner of Kearny and Union streets. This was two blocks southwest of Telegraph Hill and far to the northwest of Nob Hill. This raises the questions as to when “He built one of the first wooden houses on Nob Hill and built it something like the shape of a ship.” Assuming that Winifred Lawton’s statement (see Robert E. Lee, below) is correct, he may have built that house before 1850, when the first San Francisco City Directory appeared.

In about 1855 William and Frances Rogers had twins, Caroline E. and Catherine Rogers, the first Rogers children to be born in California, almost certainly in San Francisco. Then in about 1857 J.J.H. Rogers was born; he may have been called “Henry.”

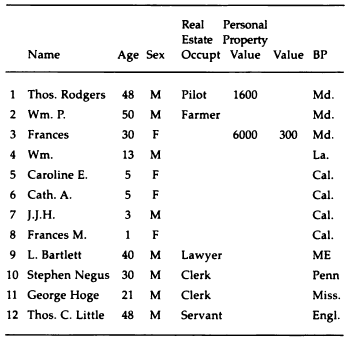

On 7 March 1859 William and Frances had a daughter in San Francisco. They named her Francis Marion Rogers and called her “Fannie.” The San Francisco City Directory for 1860-61 shows that Thomas and William are still living in the same house, at 254 Kearny Street. The 1860 U.S. census shows Thomas to be head of this household in Precinct One. Note that their surnames were misspelled as “Rodgers,” a common occurrence since census takers received their information verbally, were in a hurry, and were often not well educated. The household looked like this (BP = Birthplace; ME = Maine):

Concerning the structure of the families in this household, we can observe the following:

(1) Of the 12 people living in this house, the first 8 are kin and the next 3 are probably boarders, since they have no property and seem unrelated. In a note in the margin of the census sheet, we are told that Caroline and Cath. are twins. (2) Wm. P. Rogers is probably the older brother of Thos. since they both have the last name, were born in Maryland and are only 2 years apart in age—but they could be cousins. (3) William P. and Frances Rogers are probably the parents of the 5 children and Thomas is probably a bachelor. Yet Thomas is age 48; he could be a widower, with or without children.

However, questions arise: (1) Fannie Roger’s only living child (in 1987), Don Lawton, is sure that he never heard his mother tell of having any older brothers or sisters, nor of there being twins in her family. (2) At the time Fannie’s parents died or disappeared when she was age 13, there is no indication that anyone in the family (only J. J. H. / Henry? was living) came to her rescue or support. (3) Thomas Rogers, who is younger than William, and apparently less affluent, is listed as the head of the household. This would make more sense if he were the father of some of the children.

Aside from family structures, at least three other things are curious or puzzling: (1) Frances Rogers owns a large amount of real estate while her husband, William, has none. Since she was married at such a young age, it seems highly unlikely that she had been previously widowed and is now holding the property in trust for one of her children by the previous marriage. (2) William P. Rogers, who we know was a sea captain or pilot, lists his occupation a “Farmer.” Yet in the 1860 City Directory he was listed as a “pilot.” (3) There is an 8-year gap between William (age 13) and the next younger children (twins, age 5). Yet children born during this time could have died in infancy.

Finally, the families appear to be fairly affluent, since one or both of them own a large house and have a servant.

On 5 October 1861 William P. Rogers and his wife, Frances, “of the city of Oakland” sold their portion of Block 25 on Kellerberger’s survey to Thomas for $1,000 (Deed Book L. p. 257). Moreover, William does not appear in the San Francisco Directory and Business Guide for 1862, or any year thereafter.

In early 1862 William Rogers, Frances’s husband, died in San Francisco. His obituary in the Alta California (Thursday, February 20) read: “Died. In this city, February 19th. Capt. Phoenix Rodgers [sic], a native of Baltimore, Md., aged 52 years. Friends and acquaintances are respectfully invited to attend the funeral at 2 p.m. to-morrow, (Friday) from No. 1112 Kearney Street” [the home of his brother, Thomas Rogers]. He was buried in Calvary Cemetery, a Catholic cemetery in San Francisco. Fannie Rogers was age three at the time of her father’s death; she barely knew him.

Note that William died less than two years after the 1860 census. If at the time of the census he were seriously ill and uncertain of how long he might live, this might help to answer several questions concerning that census record: William might have (1) asked his brother, Thomas, to take over as head of the household, (2) transferred all his assets to his wife, Frances, and (3) retired from active duty as a sea captain, listing his occupation instead as “Farmer”—perhaps on his land in Alameda County where the climate seemed better and the pace of life more relaxed.

Frances and Thomas are Married. After the death of her husband, William, Frances was apparently in a difficult position, with a number of young children to raise and no apparent means of support—although she may have been joint owner of land in Oakland and Alameda County, and she had $6,000 in her own name according to the 1860 census. Thomas, her former husband’s brother, whom she had known for many years, was single. So they apparently did the obvious, sensible thing: they married, sometime between 1862 and 1868, probably in either San Francisco or Oakland. We have been unable to find a record of this marriage. Almost all San Francisco marriage records, and other vital statistics were destroyed by the great San Francisco earthquake and fire of April 1906. Although there are apparently complete, indexed marriage records in Alameda County for the years from 1854 on, this marriage is not recorded.

Sometime between 1862 and 1867, Charles T. Rogers was born—probably in San Francisco. The 1866 date comes from the 1870 U.S. census. The 1861 date is from Mountain View Cemetery records at the time of his death. His mother was Frances Rogers. Thomas was probably his father.

The 1862-63 San Francisco City Directory shows that Thomas Rogers, a pilot, has moved to 1112 Kearny and has his office at 13 Vallejo. The next year his office is listed as the Old Line Pilot Office, at 811 Front Street. Then in 1864 he apparently retired, for his occupation is shown as “ex-pilot” still residing at 1112 Kearny. This listing continued until 1867.

In early 1864 tragedy struck Frances Rogers again; her eldest son died. A short obituary in the San Francisco Evening Bulletin of February 1 states: “Died. In this city February 1st, William Henry Rogers, son of the late Captain William and Frances Rogers, aged 17 years and 8 months.”

Move from San Francisco to Oakland. In mid-October 1867 Thomas, Frances, and their children moved from San Francisco to the city of Oakland, which in those days included what is now called “Berkeley.” Land deeds show that by April 1868 Thomas and Frances were married.

On 8 May 1870, Catherine A. Rogers, one of Frances’ twin daughters, died in Oakland—in her youth and unmarried. In her brief obituary The Bulletin (San Francisco) gave her name as “Katherine Rogers, twin daughter of the late Capt. William P. Rogers, aged 18 years.” We believe that Catherine died at the age of about 15 years and 6-7 months (based on the information given in 1875 at the death of her twin sister). We have been unable to find a record of her burial. Thus, Frances had to endure the death of her husband and two of her children.

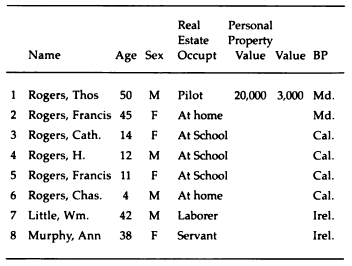

The 1870 U.S. census for Oakland, California, gives us a clear picture of the Rogers family. On 20 July 1870 it looked like this (BP = Birth place; lrel = Ireland):

Note the following:

- According to this 1870 census, Thomas was only 5 years older than Frances (50 vs. 45) whereas in the 1860 census he was 18 years older (48 vs. 30). These are major age discrepancies.

- Catherine Rogers is shown as age 14, attending school. Yet Catherine died 2 months before the census was taken. Could it have been Caroline E. Rogers who was age 14 and in school? She was probably age 15.

- All of Frances’s property has been shifted to her husband, Thomas. Could she have done this because she was ill or had a life-threatening disease?

- H. Rogers is age 12 and in school. This must be our J.J.H. Rogers, whose full name we do not know. He may have been called “Henry.”

Sometime before mid-1872 the Rogers family apparently left Oakland and returned to live in San Francisco.

Then suddenly on 13 June 1872 Frances died in San Francisco, probably of a disease, since she was still quite young. Her obituary, published on June 14 and 15 in the Alta California, the San Francisco Evening Bulletin, and the San Francisco Morning Call read:

In this city, June 13, at 6 o’clock P. M. Frances, wife of Capt. Thomas Rogers, a native of Baltimore, Md., aged 48 years. [Oakland, New Orleans and Baltimore papers, please copy]. Friends and acquaintances of the family are respectfully invited to attend the funeral on Saturday, June 15th, at 101/2 o’clock A. M. from St. Mary’s Cathedral, corner of California and Dupont Streets (San Francisco], without further notice.

The references to Oakland, New Orleans, and Baltimore imply that she was thought to have relatives or friends living in those cities. The Calvary Cemetery record gives her age at death as 48 years and 4 months. She was buried in the Rogers plot (6 – 7 – 2 – 476).

On 3 February 1873 Thomas Rogers made his last land transaction in Alameda County, selling land he owned at 15th and West streets in Oakland. This was apparently the last land he owned in the East Bay. In this transaction, it was noted that he now lived in San Francisco.

In 1875, only three years after Frances’ death, her second twin daughter, Caroline E. Rogers, died in San Francisco—in her youth and unmarried. The Alta California and San Francisco Morning Call published the same obituary ‘Died. In this city June 11th, Miss Caroline Rogers, daughter of the late Capt. Wm. P. Rogers, aged 20 years and 8 months.

She heard the song triumphant

That fills all space Elysian

And all her pure heart prayed for

Has met her raptured vision.

“Friends and family are invited to attend the funeral this day (Sunday) at nine o’clock a.m. from St. Mary’s Cathedral.” She was buried in the Rogers family plot at Calvary Cemetery.

Thomas was now alone with a family to raise. What happened next is not clear. According to one oral family tradition, he died shortly after his wife, Frances, probably in San Francisco. The last listing for a Thomas Rogers (probably ours) in the San Francisco City Directory of this period appeared in the 1876/1877 edition. It read: “Rogers, Thomas, master mariner, dwelling: corner Sierra and Louisiana.” In 1876 Fannie would have been about 17 and Charles about 10 years old.

Nome Peet recalls hearing that after his wife died, Thomas left his daughter, Fannie, with Judge Burnett in Santa Rosa, then went back to sea, and was not heard of again.

Fannie Rogers’s Relationship to Robert E. Lee. There is a long and impressive tradition within Fannie Rogers’s descendants indicating that she was related (at least indirectly) to the famous Civil War General Robert E. Lee (1804-70) of Virginia. Yet we are not yet sure which of Fannie’s parents or other close relatives was related to the Lees. We have done our best for 20 years to find this connection and have hired several professional genealogists to help us. We have made considerable progress—but have not yet been able to prove that a relationship exists. Genealogists interested in a detailed discussion of what we know and don’t know about four possible links to Robert E. Lee, please see Appendix E.

One of our best sources of information about this relationship is Winifred Lawton Seymour, who was Frances O’Donnell’s granddaughter, and Fannie Rogers’s eldest daughter. Though Winifred never met her grandmother, Frances, she must have heard many stories about her from Fannie. In 1967, when Winifred was 82 years old and had an excellent memory, she wrote several letters about her parents to her niece, Marilyn Zurcher. In one of these, dated 9 January 1967 she had this to say about the early lives of her maternal grandparents:

Grandmother’s maiden name was Fannie Rogers. Her people came from the South. Her father was a sea captain and owned his own ship, which he sailed from the South into San Francisco. He built one of the first wooden houses on Nob Hill and built it something like the shape of a ship. Fannie was related to Robert E. Lee. She told me she had seen letters from him to members of her family.

In a letter to Marilyn from about 1975 titled “Lawton History,” Winnie added a few details:

My mother, Fannie Rogers, was horn in San Francisco. Her family came from Virginia. General Robert E. Lee was a relative of theirs. My mother told me of hearing a letter he wrote to her family.

Marilyn Zurcher recalls (1987) hearing Winifred and Helen Lawton say “that Fannie’s father came from Georgia and her mother came from Virginia, and she was either from the Shirley Plantation [in Virginia] or closely linked with it. She gave me a brochure of the Shirley Plantation. Fannie’s father was a clipper ship captain.” This plantation was long the home of the Carter family that intermarried extensively with the Lees. Exhaustive searches of three Lee and two Carter genealogies have failed to uncover any woman with the given name “Frances” born in Maryland in about 1825.

Fannie’s youngest son, Don Lawton, had always thought that “Fannie was a Scotch lass, of Scotch descent, but her father was English.”

In January 1987 Ed Martin (Fannie’s grandson) recalled:

Fannie was a descendant of Robert E. Lee in the direct line. That’s where I got my first name, Edward, which was his middle name. Fannie had three letters from Robert E. Lee and was very proud of them. She used to talk about them a lot. She did it so much that Frank Lawton [her husband] finally got fed up with it and tore up all her letters. Fannie was very sad for she prized them highly.

Ed recalls hearing this from his mother, Helen Lawton Martin, who died when Ed was age 15.

The name “Lee” appears several times in the names of Fannie Rogers’s descendants. Her granddaughter (Hazel Lawton’s daughter) was named Nancy Lee Shurtleff, and Nancy’s daughter was named Sandra Lee Miller.

Remember, these are only recollections and have not yet been proven (See Appendix E).

Fannie’s Early Years (1859-83). As noted above, Francis Marion (“Fannie”) Rogers was born on 7 March 1859 in San Francisco, California, the daughter of captain William P. Rogers and Frances O’Donnell. She grew up in San Francisco, living in a fairly affluent family. Apparently, she had only one sibling who survived and with whom she kept in touch, a brother named Charles T. Rogers, who was a year or two younger than she was—although the 1870 census shows him as seven years younger. As for J. J. H. (Henry?) Rogers, apparently her elder brother (about two years older), we have been unable to find where he lived, what he did, and when or where he died.

In 1967, Fannie’s eldest daughter, Winifred Lawton Seymour, wrote:

When my mother [Fannie Rogers] was very young, she lost both her father and her mother. They had plenty of money, but the man who was appointed her guardian used up their money. He got in touch with a very nice family in Santa Rosa who were willing to let my mother board in their home. It was the Hood Family, well known in Santa Rosa. My mother attended a school there known as Christian College. She loved Santa Rosa and all the lovely friends she had there.

Don Lawton recalls slightly differently that the guardian absconded with the funds. Nothing was ever seen or heard of him again.

Note that Dora Hood, who graduated from Christian College (in May 1877), became one of Fannie’s dearest friends. She married a Burnett. This explains why Fannie’s youngest daughter, Dorothy Burnett Lawton (Peet), recollected that Judge Burnett’s family in Santa Rosa raised Fannie after her parents died, and she boarded at their home during college.

We know little about what happened to Charles T. Rogers after he was orphaned at about age 19. He may well have found a job in the Bay Area and been able to support himself.

While it is clear that Fannie lived in Santa Rosa after her mother, Frances Rogers, died in June 1872, several important questions remain: (1) When did she move to Santa Rosa? Probably between 1872 and 1876. (2) Did she move there while her stepfather, Thomas, was still alive, or after he died or disappeared, and she was orphaned at about age 17? (3) Who chose the family in Santa Rosa to be her guardians and why? (4) Which family in Santa Rosa did she board with—the Burnett family or the Hood family or both?

One theory seems plausible—the Burnetts may have been relatives of the Rogers! Two Burnett brothers are a part of our story, largely because they married two sisters—both with the surname Rogers. All four were born in Tennessee—in adjoining counties.

The two sisters were the only daughters of Peter Rogers (born in about 1788 in Tennessee; died in 1858 in Clay County, Missouri; parents unknown) and Sarah “Sally” Purtle (daughter of George Purtle, Sr.). Peter and Sarah were married on 9 August 1806 in Davidson County, Tennessee.

The first brother (and the younger of the two) was Glenn (also spelled “Glen”) Owen Burnett. Born on 16 November 1809 in Davidson County, Tennessee, he married Sarah M. Rogers on 6 January 1830 in Hardeman County, Tennessee. She was born in about 1815 in Wilson County, Tennessee, and died in 1889 in Santa Rosa, California. As part of the Restoration Movement (to restore Christianity to its original foundations), they arrived by wagon train in the Oregon Territory in October 1846. There he became very well known as a preacher within the Church of Christ, as described in the book Christians on the Oregon Trail 1842-1882, by Jerry Rushford (1997). In 1857 Glenn and his family moved to California, where they settled in Santa Rosa and he continued his church work (see History of the Disciples of Christ in California, by E. B. Ware, 1916). He was one of the founders of Christian College, which opened there on 23 September 1872 and graduated its first class in 1873; he was also a member of the board of trustees. Glenn Owen Burnett and his wife, Sarah Rogers had eight children, born between about 1832 and 1850. If Fannie Rogers had lived with this family in Santa Rosa, their youngest child (James) would have been at least nine years older than Fannie. Interestingly, one of their sons was named Francis I. Burnett. Glenn Owen Burnett and Sarah Rogers are buried in Santa Rosa.

The second (and most famous and elder) brother was Peter Hardeman Burnett. Born on 15 Nov. 1807 in Nashville, Davidson County, Tennessee, he married Harriet Walton Rogers on 28 August 1828 in Hardeman County, Tennessee.

She was born in about 1811 in Wilson County, Tennessee, and died on 19 September 1879 in San Francisco. Peter and Harriet had six children, born between 1829 and 1841 in Tennessee and Missouri. In 1839 he was admitted to the bar in Missouri and began practicing law. In 1839-40 he was appointed district attorney. The family moved to the Oregon Territory in 1843, then on to California in late 1848 after learning of the discovery of gold. Settling in San Jose (California’s first state capital, 1849-51), Peter Hardeman Burnett was the first civilian (not military) governor of California, serving from 1849-51. While he was governor, the gold rush began (1849) and California was admitted to the Union (9 September 1850 as the 31st state). In 1857 Burnett was appointed justice of the Supreme Court of California. In 1863 he founded the Pacific Bank of California and was president of it until 1880. Also, in 1880 his fascinating autobiography, Recollections and Opinions of an Old Pioneer, was published. He died on 17 May 1895 in San Francisco of old age and was buried near his wife and some children in Santa Clara Mission Cemetery—after a long and very distinguished career.

However this “Judge Burnett” never lived in Santa Rosa, so Fannie could not have lived with him or his family there.

Why do we give genealogical and historical details about these two Burnett families? First, because these two Rogers wives may explain why Fannie Rogers was sent to live with a Burnett family in Santa Rosa. Second, because these Rogers wives may be part of our family’s connection to Robert E. Lee. And one other reason—read on!

The other family that Fannie is said to have stayed with in Santa Rosa was the family of Dora Hood. Dora was about Fannie’s age and probably her best friend. Dora’s parents were Mr. and Mrs. Thomas B. Hood of Santa Rosa—both founders and supporters of the Santa Rosa Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) in Santa Rosa. Interestingly, in 1875 (roughly a year before Fannie moved to Santa Rosa) Dora married Albert Glenn Burnett, the youngest child of Glenn Owen Burnett and Sarah M. Rogers.

Born 9 April 1856 in Bethel, Polk County, Oregon, Albert grew up in California. In 1873 he settled in Santa Rosa with his parents. Albert attended Christian College and graduated in 1875—the same year he married Dora Hood. He was then ordained to the ministry of the Disciples of Christ and preached at Healdsburg, Santa Rosa, Modesto, and San Francisco. After that Albert became a teacher and taught school for 10 years. In 1887 he was admitted to the California state bar and began to practice law. A year later he was elected district attorney of Sonoma County, and re-elected in 1890. In 1896 he was elected superior Court judge of Sonoma County. In 1906 he was elected justice of the District Court of Appeals for the northern judicial district of California. According to Ware (1916, p. 318-19), “Judge Burnett is one of the most polished political orators of the State and for years the most popular man in public life in Sonoma county.”

How interesting! There was another “Judge Burnett” and he did live in Santa Rosa. Therefore, the recollections that Fannie boarded with “the Hood family, well known in Santa Rosa” (Winnie Lawton, 1967) and with “Judge Burnett” (Dorothy and Nonie Peet), may both mean the same thing! And Nonie’s mother, Dorothy Burnett Lawton (Peet) could have gotten her middle name from any of three Bumetts: Albert (most likely), Peter, or Glen—or perhaps from all three!

If Fannie’s parents chose this family for her to live with, why might they have done so? (1) Albert’s mother, Sarah M. Rogers, may have been a relative, although we have been unable to prove this. (2) Since Fannie’s parents were both Catholics, they may have wanted a family with strong Christian values and even perhaps a place where she could attend a Christian college.

When Fannie was a girl, she started to keep a scrapbook, which still survives. She kept it in a large (81/2 by 13-inch) leather bound ledger book containing 400 pages. On the spine is printed “CASH-BOOK” and across the top of many of the lined pages toward the front of the book is written, in an adult hand, “Order Book for 1875.”

Many of these pages are filled with handwritten orders, and some of these curiously contain handwritten Chinese characters. This suggests that she started to keep it no earlier than 1876, which is supported by the fact that the earliest dated documents in the book and Fannie’s earliest handwritten dates both are from 1876, when she would have been 17 years old. Nevertheless, toward the back of the book (p. 352) Helen Lawton, Fannie’s daughter, wrote in 1902, “Mama started this book when she was 8 years old [i.e. in about 1867] and has some of the old writings and sayings in it.” Fannie apparently kept adding poems and letters to the volume until about 1882. Helen Lawton later used the last half of the book for a detailed diary during her college years.

In the first half of this scrapbook Fannie pasted hundreds of small poems, clipped from magazines and newspapers. These poems are all sentimental, romantic, spiritual, sweet, and pastoral. A sampling of titles includes “Save the Sweetest Kisses for Me,” “Trust in God and Do the Right,” “I Would I Were a Child Again,” “Cupid’s Foibles, Follies, and Fancies,” “Life is Death Where Love’s Denied,” “Repentance,” and “Life.” On the side of one verse of many of these poems is penciled in “my self,” indicating that they struck a special responsive chord in young Fannie. Virtually none of the clipped poems were by famous authors. Toward the middle and back of the book we begin to find more of Fannie’s own writing. She transcribed quite a few poems by famous poets (especially Lord Byron) and composed little romantic letters or poems to her friends.

There is good reason to believe that Fannie started to keep this scrapbook during her college years. She went to college at Christian College in Santa Rosa, about 45 miles north of San Francisco. A picture of the college’s large main building is found in the scrapbook, as well as lengthy published speeches, strongly religious and inspirational, given from the college’s fourth and fifth commencements in May 1876 and 1877.

A long article (from an unknown newspaper) in Fannie’s scrapbook titled “Christian College Commencement” begins: “The Fifth Annual Commencement of Christian College was held on Thursday, May 10th [1877]. “Miss Dora Hood” was one of the six students—four unmarried women and two men—in the graduating class. From the platform she read her thesis titled “Leave the Past,” which was praised in the article as “a real gem.” Note that if the Fifth Annual Commencement was in 1877, then the first was probably in 1873. Yet this article raises a question: If Albert G. Burnett married Dora Hood in 1875, why is she listed as “Miss Dora Hood” in this article of May 1877?

The most romantic handwritten letters, notes and poems are reserved for Melville Owen, who was apparently Fannie’s sweetheart. Clearly, she wrote these while daydreaming, trying out then crossing out numerous floridly inscribed salutations and closings for each one: “Yours in loving affection”, “Ever yours”, “Forever”, “Your friend”, “Yours as ever.” Two handwritten headings begin: (1) “Darling. San Francisco, June 7th, 1876. My Dearest Melville”; (2) “Oakland Dec. 28th 1878. ‘Tis night. Melville Rolland Owen, Bakersfield P. Kern Co., California.” She always signs her own name “Fannie Rogers.” It is not clear whether Fannie composed the poems or borrowed them: Here are four short examples, written to Melville:

Though hill and dale divide us

And my face you cannot see

Remember there is one dear

That ofttimes thinks of thee

Words alone cannot unfold

The love I feel for thee

For thou art more precious far

Than costly gems to me

When dearest friends around thee twine

And all is mirth and glee

I ask thee but to pause a while

And give one thought on me

I will think of thee often when thou art far

I will liken thy smile with the night’s fairest star

As the ocean still breathes of its home in the sea

So in absence my spirit shall murmur of thee

Fannie also, apparently, asked friends to write in her book, as the following:

Dear Fannie –

As deep as the dark blue ocean,

As clear as the pearly sea,

Such is my soul’s devotion.

Such is my love for thee.

Your dear friend, Vina

Oakland, Cal. Aug. 24,1881.

There is a word in every tongue

That speaks of friendship dear.

In English ’tis “Forget-me-not”

In French, ’tis “Souvenir.”

“Forget-me-not” this simple boon

I only ask of thee

Oh, let it be an easy task

Sometimes to think of me.

May [Diggs]

We are quite sure that Fannie attended Christian College, but we do not know whether or not she graduated. The fifth and last class apparently graduated in May 1877.

In about 1877, at age 18, Fannie returned to San Francisco and worked there until about 1882. The 1877 San Francisco City Directory shows her residing at 934 Howard Street and working for Palmer Brothers, a clothing, furnishing goods, and auction store at 726-34 Market Street. In 187980 she was a saleslady there, and in 1880-81 she was working as a milliner (one who designs, makes, or sells women’s hats) for Mrs. M. A. Soper.

A full-page handwritten entry in her journal raises questions about where Fannie lived in 1878. On the top line is written: “Oakland, Dec. 28th ’78” [1878]. Below that: “Tis night. Melville Rolland (??), Bakersfield, Kern Co., California. / Miss Maytie Phillips, with Palmer Bros., San Francisco. / 1878), F.? R. Proctor – Darling [Santa Rosa], Mrs. A.G. [Albert Glen] Burnett (Santa Rosa.”

The Proctors and the Bumetts were close friends, who played an important part in Fannie’s later life. Names of other woman friends found fondly written by Fannie in this book include Sallie De Angelis (1876), Miss Dora Hood (Santa Rosa), Miss May Diggs, and Miss Eva Diggs (Half Moon Bay).

Photographs were taken of her in San Francisco in 1881 and 1882, and a newspaper article notes that she was residing in San Francisco when she attended a New Year’s Eve dance on the last day of 1881. Fannie seems to have left San Francisco in 1882, but it is not clear where she went.

Charles T. Rogers never married but lived in the Oakland-Berkeley area for most of the rest of his life.

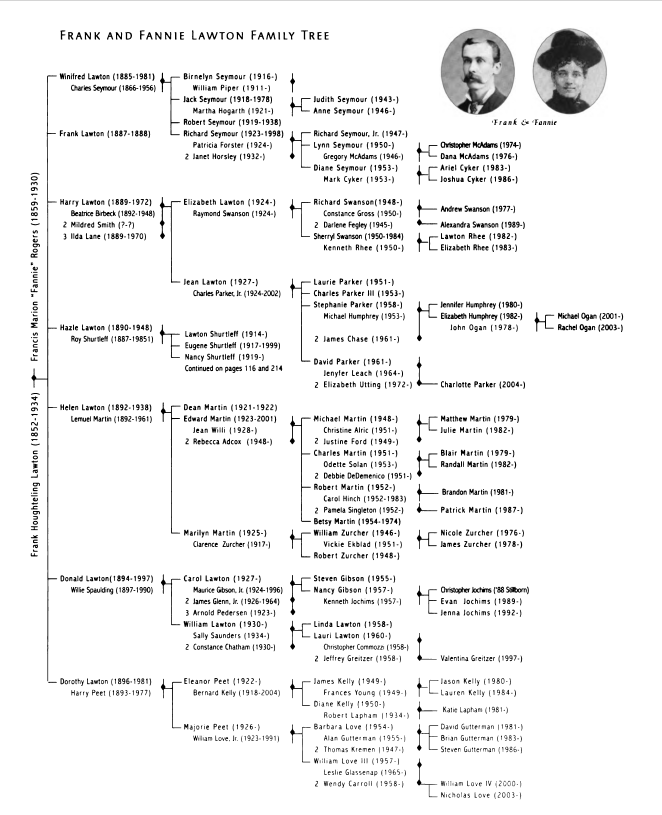

Frank and Fannie Start a Family (1884-1900). Recall that Frank Lawton and Fannie Rogers were married on 17 May 1884 in San Francisco. They wasted no time in starting a family. Their first child, Winifred Marion Lawton, was born on 19 March 1885, in San Francisco, just 10 months after her parents’ marriage. Winnie’s middle name was the same as that of her mother. In the coming years, Frank and Fannie had seven children, six of whom married and themselves had children. All (except Dorothy, who willed her body to science) were buried in the Lawton plot at Mountain View Cemetery, Oakland, California:

- Winifred Martin Lawton, born 19 March 1885 in San Francisco, California. Married Charles Birney Seymour on 19 June 1915 in Berkeley, California (later divorced). Died 30 Nov. 1981 in Sebastapol, California.

- Frank R. Lawton, born 39 Sept. 1887 in Berkeley, California. Died 16 March 1888, Berkeley.

- Harry Rogers Lawton, born 19 May 1889, Berkeley, California. Married (1) Beatrice Joyce Birbeck on 14 June 18923 in Piedmont, California. She died on 16 Oct. 1948 in Seattle, Washington. Married (2) Mildred (Griffiths) Smith on 5 Nov. 1948. Divorced. Married (3) Ilda Lane on 15 June 1956 in Los Angeles, California. She died on 17 Feb. 1970. Harry died 3 Oct. 1972 in Walnut Creek, California.

- Hazle Clifton Lawton, born 25 Sept. 1890 in Berkeley. Married 13 Oct. 1913 to Roy Lothrop Shurtleff in Berkeley. Died 19 May 1948 in Orinda, California.

- Helen Gladys Lawton, born 25 Sept. 1892 in Berkeley. Married 27 Aug. 1919 to Lemuel Edward “Ed” Martin. Died 17 May 1938 in Berkeley.

- Donald Carroll Lawton, born 2 Aug. 1894 in Berkeley. Married 6 July 1922 to Willie May Spaulding in Oakland, California. Died 2 June 1997 in Berkeley.

- Dorothy Burnett Lawton, born 3 Aug. 1896 in Berkeley. Married 14 Aug. 1920 to Harry Eldridge Peet in Berkeley. Died 8 March 1981 in Walnut Creek, California.

Sometime between 1877 and 1884 (see 1880 census), following her husband’s death in Clyde, New York, Susan A. Lawton, Frank’s mother, moved to San Francisco to be near or live with Frank. On 4 August 1884, just 3 months after he was married, she presented the new couple with a large and beautiful Bible, which she inscribed and dated. Measuring 11 by 13 inches, and almost 4 inches thick, it weighed 12 pounds, and contained pages for recording births, marriages, and deaths in the family. These are a treasure trove of genealogical information.

In about 1885 W. D. Lawton, Frank’s brother and co-worker or boss at the shirt business, left San Francisco, probably to return to the East Coast for unknown reasons. Frank took over the shirt business. His high-quality and fancy custom-made men’s shirts (with special turn-back cuffs and buttons) for the upper classes brought him a good income.

In 1885 Frank and Fannie moved from San Francisco across the Bay to Berkeley. This small rural town had first attracted attention when the University of California was established there in 1868; Berkeley was established as a town (separated from Oakland) and incorporated in April 1878. On Channing Way near Shattuck in Berkeley, Frank had built a fairly small but nice new house (Winnie called it a “cottage”). The Lawton family lived prestigiously near the “steam train,” which Frank would board each morning, and disembark at the Oakland Mole—a very long pier or wharf stretching from southwest Oakland far out into the Bay, with train tracks running out to the end, where the ferry boats docked. From there, Frank caught the ferry to San Francisco.

On 24 July 1886 Frank’s mother, Susan A. Lawton, died of heart disease at her son’s home. A newspaper in Clyde, New York, listed her as dying “at her son’s home in San Francisco,” but she probably died at his home in Berkeley. Frank buried her the next day at Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland in a small plot (plot 19, lot 159), which he probably purchased at that time for Susan’s burial. Established in 1863, this cemetery was (and still is) the largest and oldest cemetery in Alameda County.

On 29 September 1887 Frank and Fannie’s second child and first boy, Frank R. Lawton was born. Then tragedy struck. On 16 March 1888, when the infant was only 5 months and 28 days old, he died of meningitis. The next day Frank, his father, went again to Mountain View Cemetery and purchased plot 26, lot 44. There he buried his tiny son. It is not clear why he purchased this plot when he apparently already owned the one in which he buried his mother, unless the former one was too small and / or was in a less favorable location. On 26 October 1896 he decided to consolidate his two plots. So, he returned plot 19, lot 159 to the Mountain View Cemetery, for credit, and at the same time had Susan A. Lawton disinterred and reburied in plot 26, lot 44, near his small son. Today plot 26 remains the final earthly/physical gathering place for many members of the Shurtleff and Lawton families and holds a precious store of both memories and genealogical information—as Frank Lawton may well have envisioned over a century ago.

The family’s third child, Harry Rogers Lawton, was born 19 May 1889, at home on Charming Way in Berkeley. It was time for a move to larger quarters.

So, in about 1890 Frank and Fannie had a new and much larger home built in Berkeley, at 2211 Durant Avenue, just above Fulton, in Berkeley. The house was on the left-hand side of Durant as you stood looking uphill (east), not far from what is today the southwest corner of Cal’s Edwards Track Stadium. The Lawtons lived in this home for the next 44 years. Containing 10 rooms, it was basically a four-story house, with an elevated first floor (about seven feet above ground level), a large, raised basement, a second floor containing the bedrooms, and a spacious attic with a clear view of San Francisco. When the big brick chimney was built, two colorful glazed tiles, each about one foot square, were mortared into the outside back. They bore the silhouettes of a boy and a girl and were in full view as one came up the driveway. A great house in which to raise a large family, it became in the coming years a favorite gathering place for the many neighborhood kids. For Lawton Shurtleff, who played there in the mid-1920s, “It was simply a fantastic home for us young kids. Laundry chutes, dumbwaiters, an attic full of all types of mementos and souvenirs to play hide and seek in made it the most fascinating place in the world. It really should have been preserved as an historic monument.” New attractions were added as time went on. A photo of the house taken in the early 1890s shows Harry and Hazle seated on the front steps. At the back of the large backyard, a huge barn was built. In it were kept one or more horses, a surrey, and a phaeton. It is clear that by this time Frank’s shirt business must have been prospering.

Four more children were born at exactly two-year intervals in the new home in Berkeley: Hazle Clifton Lawton (25 September 1890), Helen Gladys Lawton (25 September 1892), Donald Carroll Lawton (2 August 1894), and the last child, Dorothy Burnett Lawton (3 August 1896). Each of the children was weaned in a handsome, solid walnut wooden highchair (now in the possession of her great-grandson, Bill Shurtleff), patented in 1876. The front tray flipped up and over the back, out of the way, when the child was to be removed. And all were rocked in Fannie’s little rocking chair (now with her great-granddaughter, Barby Love Gutterman) in the sewing room.

In about 1891 Frank decided to rename his thriving shirt business from W. D. Lawton & Co. to F. H. Lawton & Co., and to move it to 305 Kearny Street In 1894 he moved it again, to 229 Kearny.

Raising a Family (1900-20). The six surviving Lawton children turned into a wonderful, tightknit family. And their early lives were full of fun and adventures. Most of them attended Dwight Way School (later renamed McKinley Grammar School) and Berkeley High School.

Starting in about 1900 Frank and Fannie started a lasting tradition of taking the family on a two-month vacation each summer, in part to get away from the fog and cold of Berkeley to a warmer place. The kids loved it. As Don Lawton recalls the first trip:

When we went to Los Gatos for the summer, we called Berkeley’s only baggage smasher, whose name was John Shekumpshun Sherman Boyd, to help with our belongings. He was so big and reckless, he’d smash everything he put on his horse-drawn wagon. Now father had this large trunk, and he wrapped it in a long rope that he took along to make us a swing. Well, you could hardly see the trunk it was wrapped in so much rope. Boyd’s wagon took us down to the train depot. The manager there was a neighbor friend of ours, but he said. “Mr. Lawton, this trunk cannot go. It’s way overweight.” Father said, “Well, it has to go. We have our train reservations and we’re all here ready to go. I want you to put it on the train.” The manager explained that it would just be taken off again later down the line, but he put it on anyway. Apparently he telegraphed ahead, because when we arrived at The Mole the conductor walked up immediately and said to mother, “I’m sorry lady, but you have a trunk on the train here which we’ll have to remove because its overweight.” She said, “How do you know? You haven’t weighed it.” But he replied, “Well, we happen to know.” So she said, “All right.” We unroped and unroped and unroped that trunk, as the train waited. Then Fannie asked each one of us to take an armful. 1 took the underwear. Harry took the shoes. Helen took the hats, and so forth. We all got on board the train and sat there loaded down all the way to Los Gatos. The trunk went along half empty. Fannie said as we left, “Well, I guess that’ll satisfy him.”

On the way I remember I stuck my head out the window as we went thru a tunnel and my nice new white sailor hat blew off. My whole life I’ve wanted to go back and see if I could find that hat.

In Los Gatos we stayed in a house, way up on a hill, with a creek nearby. Father took that long rope off the trunk and tied it to the branch of a big tree near the creek. As we rode that swing way out over the creek, it seemed like swinging out over Niagara Falls. It was just the greatest thrill in the world.

The next year Fannie had a creative idea. She had made many close friends with families in Santa Rosa during her years at Christian College. Perhaps they might like to exchange houses with her family for the summer, especially since the Lawtons had such a spacious and attractive home. The idea worked, and for the summer of 1901 and 1902 the Lawton family stayed in beautiful big houses in Santa Rosa. One summer they stayed at the McKinley’s home and the other at Judge Bumett’s home. Dora, Judge Albert G. Burnett’s wife, was a close friend of Fannie’s from her college years.

In 1902 Frank Lawton began to diversify his business interests. He started a company named Lawton & Albee, located at 2139 Center Street in Berkeley. His partner was Marshall P. W. Albee, and they sold real estate and fire insurance, collected rents, paid taxes, negotiated loans, and served as a notary public. By 1903 Frank had telephones at his business and at home. In 1904 or 1905 Lawton and Albee separated, but continued to do exactly the same type of work. Frank’s new company, called F. H. Lawton & Co., was located a few doors down and across the street at 2147 Center Street Albee & Coryell occupied the former site. Frank’s 1906 advertisement read, “Reliable Expert Information… Carriages always in waiting.” In 1907 Frank moved next door to his former partner, to 2141 Center, and consolidated his services to real estate and insurance. By 1908 he was focusing solely on real estate.

For the summer of 1903 the Lawtons swapped houses with a family in Ukiah, located at the headwaters of the Russian River about 60 miles north of Santa Rosa. And the next summer they stayed with the Guerne family on the Guerre Ranch in Guerneville, just upstream from Monte Rio on the Russian River. The kids stayed in a big boarding house on the large Guerne Ranch and enjoyed the horses, cows, and fruit trees. Before that summer was over, Fannie took the family to see a little town she had heard about down the river called Monte Rio. They made the trip in a special railway car, sort of an open-top gondola with rows of seats in it. They found that the river was unusually wide in Monte Rio and the town was quaint and rustic. The exterior finish of all the homes was redwood tanbark rather than paint. A sign proclaimed the town the “Little Switzerland of America.” Father asked, “Do you all like this place well enough to have a summer home here?” Everyone replied, “Yes, we love it.” So Frank bought a lot and found a contractor named Mr. Proctor, who had a wooden leg. He began to build a large summer home for the Lawton family in Monte Rio on a hill overlooking the river. At the end of that summer (1904) Harry Lawton and a friend walked all the way back to Berkeley on the railway tracks.

For the summer of 1905, while the house was still being built, the Lawton family rented the highest house on the hill in Monte Rio, up behind the railway station and the Air Castle (which had two steeples and was painted red and white). To get to Monte Rio from Berkeley in those days before cars were widely used was no easy task. First the big family and baggage was loaded on a nearby train that took them to the Oakland Mole. There they loaded everything onto a ferry bound for the Ferry Building in San Francisco, where they caught another ferry going north to Sausalito or, if Sausalito was fogged in, to Tiburon. And finally, they caught a wood-burning steam train to Monte Rio. It was an all-day operation.

On the morning of Wednesday, 18 April 1906, the great San Francisco earthquake struck. It destroyed the brick building in which Frank had his shirt factory and dealt a serious blow to the business as well. Frank decided to sell that business and focus on his real estate and insurance business in Berkeley. His timing (and probably his basic perception of the market) could not have been better, for the earthquake transformed Berkeley almost overnight into a boom town, as thousands fled San Francisco. Moreover, by now Frank was probably tired of having to commute from Berkeley to San Francisco every day on the ferry anyway.

The earthquake also damaged many Berkeley schools (including Berkeley High and Cal), so school was let out early for the year. Frank’s son Harry went over to San Francisco and was conscripted into the labor force there. Don and Guy Witter jumped on a streetcar each morning, went down to the Oakland Tribune offices, and got an armful of newspapers for 5 cents each, then rode all the way back to Berkeley and sold them for ten cents each. “Read all about it, all about it,” they’d call out. There were very few telephones and no radios in those days. Each night for several days the family would stand on the front porch and watch the city of San Francisco burn.

The Lawton family took off shortly for Monte Rio, traveling by trains and ferries. For the first time they started to live in their new summer home, even though it was not yet completed. They took their blankets and slept out on the porches, here and there among the lumber, the four girls on the big open upstairs porch and the two boys on the open platform below. The view out over the river was gorgeous. In the years to come this home and haven was the place to go, not only for the Lawtons and their many friends, but for the Shurtleffs as well. Frank commuted to Monte Rio each weekend.

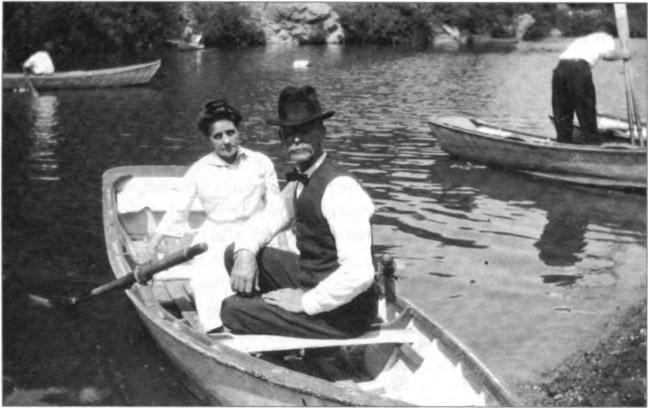

In 1906 or 1907 the family bought (for $47.50) a beautiful rowboat named the Lawton, which was built by Monte Rio’s pioneer boat builder C. W. Meadows. At least once a summer Don and friends his age (Guy Witter and Ed and Heber Steen) and Harry with his friends (separately) would row the boat down to the mouth of the Russian River at Jenner. They would leave in the morning, then sail back with the afternoon wind. One summer a young married couple on their honeymoon drowned in the river. Don had to search for them until he caught them with grappling hooks. They were still holding hands, and all that night he saw her lips, indigo blue in death. A sort of canoe, named the Smoka Pipa Hoppa, made out of barrel staves and canvas by Lowell High School boys was also kept at the Lawton house and widely used. On the river there were also motor-driven boats run by Meadows or Farnell on which the family could take a daily excursion, down to Jenner or up to the Bohemian Pool.

Swimming was a favorite sport and pastime of the Lawton children at Monte Rio, and they all became excellent swimmers, especially Harry, Helen, and Dorothy. During the first year or two they swam at nearby Monte Rio beach, but then they discovered and opened up a new area called Sandy Beach. The water was deeper there and the sand went way up on the bank. They liked to dive off a 12-foot-high platform that had been built in a wide, deep stretch of the river. Beautiful Margaret Witter, Dean Witter’s sister, was a frequent companion. The Lawton house had a big lower deck, which became the main depot or warehouse for all the kids from the Bay Area to park their sleeping bags, boats, and the like. On many occasions, as when there were Berkeley High School reunions or it started to rain, the rallying cry was “Everybody head for the Lawton cottage.” They would all stay overnight on the lower deck under the shelter of the big porch, and the next morning Fannie would cook huge breakfasts for the whole gang, featuring hot biscuits with applesauce or strawberries. The Lawton family continued to go to Monte Rio each summer until all of the kids were grown. To this day, they are still a legend around Monte Rio.

Back home in Berkeley, the kids all went to public schools. For grammar school it was Dwight Way School (on that street just below Telegraph), which was renamed McKinley Grammar School in 1907-10. Then on to Berkeley High for High School and the nearby University of California for college. All of the Lawton children except Dorothy went to Cal. In those days it was much less common for women to go to college than it is today. Frank, who had had to forego a college education himself for lack of money, must have been extremely supportive and proud of his sons and daughters.

Young people entertained themselves much differently in the early 1900s than they do today. Transportation was mostly by foot, or by horse and buggy up until about 1910. There was much more self-entertainment. Favorite past times away from home in 1909-11 (when Helen Lawton kept a detailed journal) included buggy rides, rides on “the electric” (the new Key Route trains that replaced steam trains) and “Tug rides on the Bay.” A high school would charter a big tug and leave the Jackson Street Wharf in San Francisco heading slowly for California City by Tiburon. The get-together, for couples and chaperones, featured a band and dancing on board. The Orpheum Theater on 12th Street in Oakland was the place to go for vaudeville (even clowns on unicycles) and movies. The first day of high school it was tradition for everyone to cut classes and take off to the Orpheum.

The Lawton home in Berkeley was the favorite hangout of many neighborhood kids, whose ages ranged widely. Don remembers:

We had just crowds in and out of the house. It was a center of fun and activity. The Witters had six kids just like we did: Dean, Margaret, Elizabeth, Guy, Charles, and Jack (“Babe”). Mr. Witter was a great big overweight lawyer who drove a large Thomas Flyer automobile. They lived only one block away, also on the corner of Durant Ave. Our two families were so close that our doors were always open night and day, and so were theirs. Everybody was just good friends, and we were all about the same age. We loved to play One Foot Off the Gutter on Durant Avenue. On summer evenings the Solinsky kids, who lived next door, would stand out in front of our house and call out “Winnic Winnie Wah Walr Day Day Dawton” to get us Lawtons out to play.

In those days we had a funny little thing we used to say back and forth as kids. It was in the family for years and it went like this: “Have you seen my friend Al? Al who? Alcohol. Kerosene him last night. Ain’t benzene since. Gasoline’d against the fence and took a nap-there.”

One major attraction was the big backyard playground, where Don, a budding carpenter and mechanic, had constructed, out of scrap lumber, a gigantic Ferris wheel. He also built a “Trip the Trolley” sky-diving rig that allowed a kid to leap from the hay loft of the barn and sail 100 feet in the air, supported by a pulley that raced along a taut rope (both ingenious contraptions are described in detail at the story of Don’s life).

One very popular backyard activity, in addition to baseball, was boxing. Fannie bought the kids boxing gloves. As Don recalls:

Harry and I would lace up our boxing gloves and spar. He was an excellent boxer and gave me many good tips. Later we’d start to invite some of the fellows from Berkeley High up to our house and we’d box nearly every afternoon. I remember one fellow in particular who was very small, named Waldo Colby, a tough little scrappy guy who had a peculiar way of hitting. He’d jump up in the air, pound you on top of the head, and knock you down on your knees. I’ve never forgotten it and I could never lick him.

Don went on to become the heavyweight boxing champion of the University of California.

In addition to horses, chickens and a goat were kept in the Lawtons’ backyard. On the corner by the Lawton house was Wickson’s vacant lot where Frank Lawton would graze his horses. Wickson owned a big house nearby and a barn that had a steep roof with all four sides going up to a flagpole in the middle. The Lawton kids would run up that roof trying to grab hold of the flag pole, then slide down and tear the shingles off. Wickson would raise hell with the little rascals.

In about 1908 Harry Lawton, then 19 years old, was spending a lot of time with his high school friends hanging out at Al’s Pool Hall on Shattuck Avenue, near Center Street, not far from his father Frank’s real estate business. One day Frank, growing a bit concerned, said to Harry, “Look, how would you like to have your own pool hall in our basement at home so you could invite your friends to come there?” Frank asked Don to clean out all the firewood in that part of the basement. Then he had a pool hall with a pool table built on one side of the basement and a real one-lane bowling alley built on the other. Don’s workbench was in one corner. Saturday night was bowling night for the neighborhood. Kids would come from far and wide. The family would light coal oil lamps and line them up on stands along the sides of the bowling alley and around the walls of the basement. Someone (often Don) would set the pins by hand, both full-sized 10 pins and smaller duckpins. Fannie fixed a big cut glass bowl of punch and everyone had a great time.

Dinner time, especially on weekends, found the ten-foot-long heavy oak table at the center of the Lawton dining room table packed with visitors, usually friends of the kids. Roy Shurtleff, who lived only eight blocks away, was a frequent visitor, from October 1910 on. Each weekday evening, when it was time to study, the Lawton kids would gather around the table, lighted by a large coal oil lamp that was suspended from the high ceiling and covered with an umbrella-shaped stained glass shade. In the winter, the wood-burning, pot-bellied stove gave off convivial warmth. Don Lawton recalls how

Dean Witter, who was captain of the crew at Cal, would visit the family study hall time and time again when he was in college. Harry used to go out with his sister, Margaret Witter. Dean sat right down with us and said, “Maybe I can help you with some of this mathematics.” So he pitched right in and, oh, we had a big time.

If anyone asked Hazle what she was doing on her math, she’d look up quickly and say, “Ought’s ought are oughty ought and two to carry” In other words “Nothing.”

Don remembers how on winter mornings the pot-bellied stove warmed the home.

We kids would go out in the morning before school and gather up scraps of wood from four nearby homes on Channing way that father was building. We’d load up my big coaster, bring it back and store it in the basement. Every morning, from the time we were little kids, father would get up in the morning early, get a fire started in the pot bellied stove, then come up stairs and call “Everyone up, everybody get down stairs.” We’d all jump out of warm beds just packed with comforters, run down there in our bare feet and pajamas and he’d lead us for 10 to 15 minutes of regular army calisthenics: one two one two. We’d all jump up and down, swing our arms (he’d just swing his arms because of his weak foot) and get really warm, then go up and put our clothes on and come down and have breakfast. At night I was the lamplighter. Father taught me how to turn the gas light wick on and down, without turning it off

The Lawton family had a big piano in the living room. Miss Hudson came once or twice a week to give lessons to Helen, Don, and Dorothy. Helen and Dorothy became quite good. Fannie didn’t play piano at all.

We noted earlier that Fannie had a younger brother named Charles T. Rogers, who never married. He visited the Lawtons’ home frequently and the children all called him “Uncle Charlie.” A fun-loving young fellow, Charlie was a racetrack gambler by trade, and he made fairly good money at it. He rented an upstairs apartment at about 40th and Edeline in Emeryville down near the Bay and the Temescal Race Track, and resided there with “Aunt Sophie,” his live-in, whom he never married. Charlie liked to hang out in Emeryville at Landregan & White, a saloon at Adeline and Stanford, down by the race track.

Don Lawton remembers Uncle Charlie as…

a very jovial, clean-cut and friendly, sort of free-lance, happy-go-lucky fellow. Just a good all around guy. We kids all enjoyed him and he had a lot of friends in his own world. He was always welcomed by our family because he made everyone so happy. It was a big day when he would come out on the streetcar to visit us. When we were kids we didn’t understand that some adults regarded his relationship with “Aunt Sophie” as fairly scandalous. Once I rushed up and kissed her. My elder sister Helen said, “You shouldn’t do that. She’s not your real aunt.” But everyone liked her and they were together for many years.

In about 1903 Charlie bought an old Victor Talking Machine in Oakland and took it to the Lawtons on the Horse Car. This beautiful big phonograph had a round cylinder on it, and every Saturday night for a while Frank would open the house window toward the vacant lot on Fulton Street and turn it on full blast. All the neighbors would come out and listen, as the family played “Turkey in the Straw” over and over again. No one in Berkeley in those days had anything like it, and it added music to the many other attractions of the Lawton home.

Helen Lawton’s diary (1909-11) mentions that Uncle Charlie visited the Lawton family repeatedly: He did chin-ups and played baseball with the kids in their backyard, brought them gifts of candy or money, took them to the “moving pictures shows” or to Lenhardt’s for ice cream, and sometimes stayed for dinner or all night. The family also visited him.

Charlie had a word game he liked to play with the Lawton children when they were young.

He’d say slowly and very seriously with a Polish accent: “Did you know that Izidore de Rosenberg, iz brother he is dead?” The kids would respond, “Is he?” Then Charlie, putting on a face of great distress, would answer back, “Oh no, no, no, no. Not Izzie! Izzie de Rosenberg, iz brother he is dead.” “Oh is he?” the children would reply, starting to crack up. “No, no, no, no….” Don remembers: “Well, he’d go on and on, and we’d laugh for about half an hour into tears at that damn thing!” Many of the Lawton children later entertained their children with this same story, and they in turned passed it on.

Charles T. Rogers (Uncle Charlie) passed away on 14 October 1913 at age 52 of heart disease (“chronic fatty degeneration of the heart”). He was buried in the Lawton family plot at Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland. The cemetery records show his place of death as Antioch, California, but no death record can be found in the state’s comprehensive index, nor is Charlie shown in California in the 1910 census.

Though Fannie was a “pro” at all aspects of home making, raising a family of six active children was not easy. Winnie, her eldest child, helped her a lot, and she also brought in some outside help. Starting in about 1907 Kitty Kayler, who lived in an apartment nearby, started to come in to work primarily as a laundry maid, but also to help with the house keeping. She came for many years afterwards. Then once a year a seamstress named Mrs. See from northern California would come to live with the family. She made each of the children two new sets of dressy clothes: one for summer and one for winter. The design for each child was different. The Lawton kids were always well dressed.

Each of the Lawton children was a unique person, with a great sense of humor and unusual inner strength. Winnie, the eldest by four years, looked strikingly like her mother. Strong, generous, and deeply loved and respected, she was like a mother to those younger than she was. Yet she was always ready with a limerick or a joke or a pun. Harry was full of fun and mischief, a fine athlete and a young man with a multitude of friends. Hazle was a good solid warm person and quite popular. Helen, a beautiful young lady, was a magnificent swimmer, plus an extremely popular and fun-loving leader among her classmates. She and Hazle are remembered for their wonderful laughs. Don was a whiz mechanic, a carpenter, and a track star. Dorothy was the witty, spoiled little beautiful sister to all. When everyone else had to line up in the winter to take blackstrap molasses, she was excused. Fun loving and warm, she was down to earth and ready for anything.

The last listing in the Berkeley City Directory for the real estate firm F. R. Lawton & Co. appeared in 1908. During 1910-11 Frank was working with F. R. Peake & Co. Then from 1912 to 1916 his listing was simply “F. H. Lawton, real estate, 2035 Shattuck Ave.” Don Lawton recalls that during this period he was working with Scott Martin in a real estate sales and construction company (also handling some insurance and notary business) that became very successful and lasted for many years: together with Mason-McDuffie, it played a major role in developing Berkeley. It was especially active in the Claremont territory (Although there is a Lawton Street in the Rockridge area of Oakland, it was not named after Frank, but after General Alexander R. Lawton [1818-96], a Confederate soldier and distant relative.) In the early days Frank’s company had two horses and two carriages in which to take clients around to view houses. In about 1912 the company bought its first car. A prestigious replacement for the horse-drawn vehicles, it was a large and beautiful new four-cylinder, high-wheeled Oldsmobile, which was advertised in the Chronicle: “This Oldsmobile climbed Twin Peaks in San Francisco.” A chauffeur (rather than Frank) drove the car. Frank later learned to drive in his backyard, in a 1917 Dodge touring car, a gift from his son, Don. Years later Frank bought a large Buick, which eventually ended up in the Roy Shurtleff family. Frank is remembered to have been one of the five original founders of the Berkeley Realty Board. He continued to be self-employed in the real estate business until his retirement in 1919.

Fannie Lawton as a Person. Fannie is remembered by everyone who knew her as a wonderful, remarkable lady. A tiny woman, she had great inner strength, a tremendous devotion to her family, deep religious faith, and a great sense of humor—a rare combination. Her son Don recalls:

Mother was lots and lots of fun and laughs, with her vivid Scottish expressions and little quips like “Just give ’em a lick and a promise.” Hale, hearty, and well met, she was sharp as a tack. She loved big groups and lots of kids and their friends around. She liked singing, raising Cain; she was a kick, a great sport. Fannie had lots and lots of friends, including those from her high school days in Santa Rosa. She was so friendly; just loved big teas with all her friends. She was a knockout, just a beautiful, sterling person. A sweetheart of sweethearts. Oh, God how I loved her. Everybody loved her. I only wish that everyone could have a life like we Lawton kids had, both as little kids and as grownups—with a mother and a father like we had.

Fannie is remembered by many who knew her well as a very devout Christian Scientist. Her interest began in about 1908-09. We have already seen how, as a young girl, she had a deep interest in God and things of the spirit. Birnelyn Seymour Piper recalls hearing from her mother, Winnie (who was also a Christian Scientist and referred to the incident once in writing), that prior to this time, Frank Lawton had a chronic illness, which was never discussed with his children. While living in Berkeley, he had gone to all the best San Francisco doctors, but to no avail. One day a neighbor lady stopped Fannie on Durant Avenue and said, “My husband had the same problem that yours does and he was healed by Christian Science.” Fannie, who was not aware of Christian Science at the time, started to go to church. First she went to the meetings in Wilkens Hall, a dance hall next to the old McKinley School on Dwight Way, a block or two up from the Lawton home. There and at 2300 Durant, Dr. Francis J. Philo, lecturer and teacher from the First Church of Christ Scientist in Oakland, would conduct weekly meetings. Especially impressive were the Wednesday night testimonials, when people would tell of the healings they had received. In 1910 a beautiful new church building was opened on Dwight Way, designed by the world-famous architect, Bernard Maybeck, who also designed the University of California Faculty Club. From the outset, it was packed with people for both the testimonials and the Sunday morning services. At first Frank showed little interest in all this. Then at some point while Winnie was in college (probably in about 1905 or 1906), Birnelyn recalls hearing, and Winnie noted in a list of her Testimonials, that Frank Lawton was completely healed of his ailment. But Don Lawton, who was there at the time and about 16 years old, was not aware of Frank’s former protracted illness or of any healing.

Helen Lawton’s journal shows that during 1909-11 Fannie, and quite often Frank and Winnie or Don, went to Christian Science church together. Soon they were reading The Sentinel and Mary Baker Eddy’s writings, learning of the Divine Mind and the power of God to heal. Eventually Winnie became the most active and devout Christian Scientist, though Fannie and Helen also showed deep faith.

Part of Christian Science teachings was not to discuss one’s health problems with others, and especially with those outside the family. Equally important was not to dwell on the negative aspects of life.

Fannie kept a little book in which she wrote her favorite prayers and religious sayings. Their source is not known. Here are three that Winnie copied down in the about 1980:

The power of love the world can sway

Good shall prevail.

If nought but love reign in my heart today

Nothing I do can fail.

God is my help in every need.

God doth my every hunger feed.

God walks beside me, guides my way

Through every moment of his day.

I now am strong, I now am true

Faithful, kind, and loving, too.

All things I am, can do and be

Through Christ the Truth that is in me.

I now am well, I can’t be sick.

God is my help, unfailing quick

God is my all, I know no fear

Since God and Truth and Love are here.

My Prayer

To be ever conscious of my unity with God. To listen for his voice and hear no other call.

To separate all error from my thoughts of man. To see him only as my father’s image. To show him reverence and share with him my holiest treasures.

To keep my mental home a sacred place, golden with gratitude, redolent with love, white with purity, cleansed of self will.

To send no thought into the world that will not bless or cheer or heal.

1 have no aim but to make earth a fairer, holier place and to rise each day into a higher sense of Life and Love.