** All Text on these chapter pages has been copied verbatim – with permission – from this book: “Shurtleff Family Genealogy & History – Second Edition 2005” by William Roy Shurtleff & his dad, Lawton Lothrop Shurtleff ** Text in pdf convert to word doc – any spelling errors from the book may or may not have been fixed. **

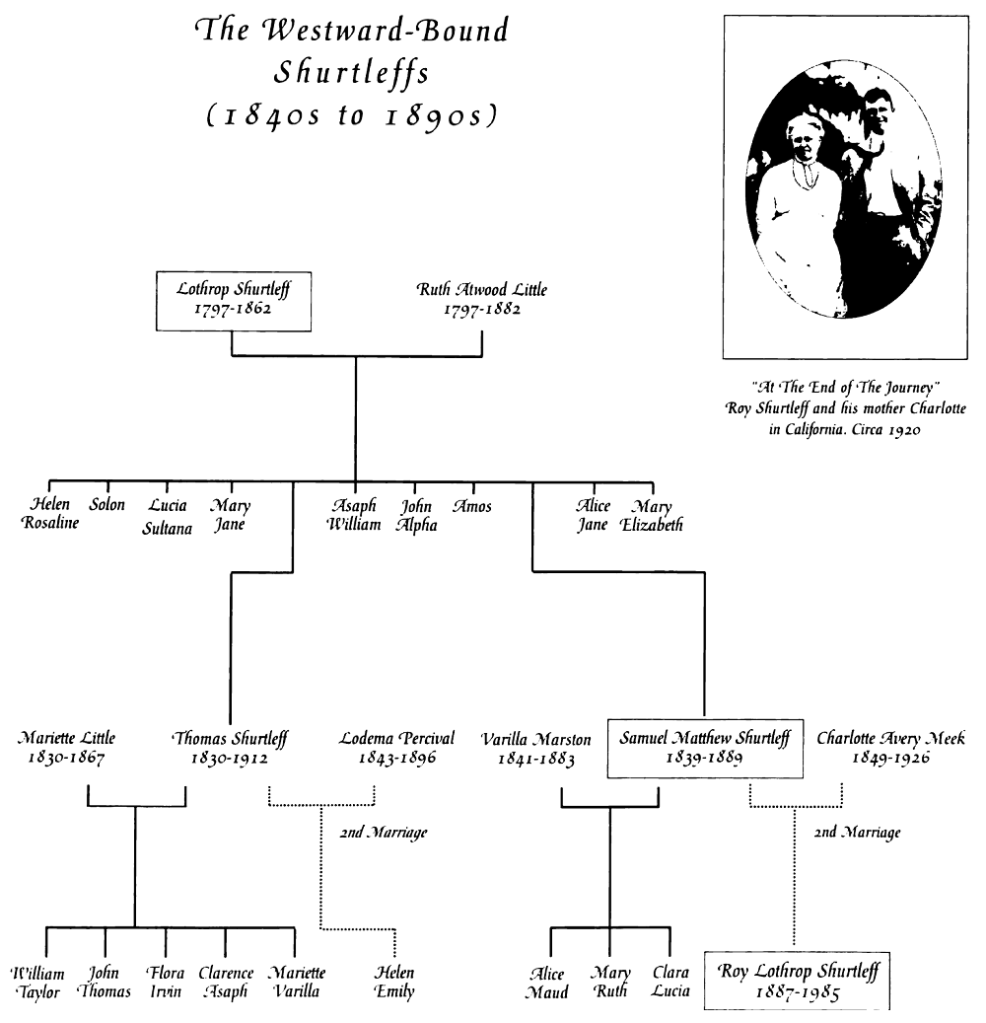

Chapter 2 told the story of how, in 1802, our Shurtleffs moved from New England to the Eastern Townships of southern Quebec, Canada. Three generations of Shurtleffs ‘ resided first in Compton, then in Hatley and Sherbrooke, and many children were born in Quebec. We now return to that story as the seventh generation of Shurtleffs in America, the children of Lothrop and Ruth Atwood (Little) Shurtleff, begin to return to the United States.

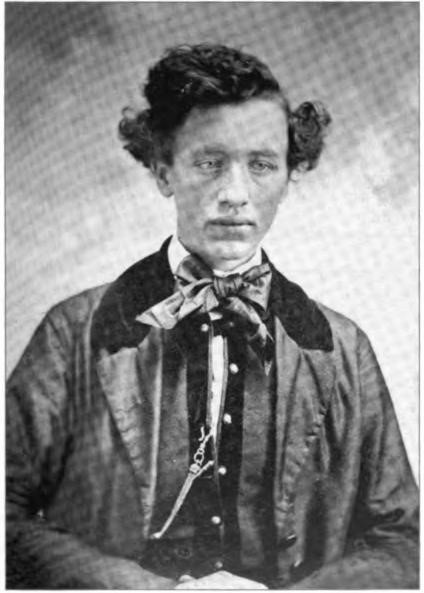

Roy Shurtleff’s father, baptized Matthew Samuel Shurtleff, went by the name of Samuel and throughout his life signed his name as Samuel M. Shurtleff. One of the seventh generation of Shurtleffs in the United States, Samuel was born the ninth of eleven children, six boys and five girls, of Lothrop Shurtleff (1797-1862) and Ruth Atwood Little (1797-1882) in Hatley, Quebec, on 12 August 1839.

Samuel died on 24 August 1889 at age fifty years and twelve days, almost one month before his baby son, Roy’s, second birthday. So, although Roy never really knew his father, Samuel and his family greatly influenced Roy and his descendants—in ways this story seeks to reveal.

The seventh generation of Shurtleffs in Quebec, Canada. All of the eleven Shurtleffs of this generation were born in Quebec, Canada, between 1822 and 1843. The first two (Helen and Solon) were born in Sherbrooke; the other nine were born in Hatley, not far to the south. Of the eleven, nine married, but only three of these nine married in the land of their birth, Quebec: (1) Lucia Sultana Shurtleff married Tyler Harry Moore Hyndman. (2) Solon Shurtleff married Rebecca Johnson. (3) Thomas Shurtleff married Mariette Little. The remaining six children married in the United States.

Leaving Canada. By the mid-1800s Quebec appeared to lose its appeal for our Shurtleff family. Lothrop and Submit (Terry) Shurtleff had eleven grandchildren and twenty-three great-grandchildren, all born in Quebec; yet only six of their great-great-grandchildren were born there. There is evidence that the heavy cultivation of potatoes had robbed the rich Quebec bottomland of much of its productivity, making it less attractive to farm. Or, perhaps, as in New England, civilization was again encroaching, and these Shurtleffs tended to move along to look for greener pastures. From this potato-and-whiskey-producing area of Quebec, their next destination was south and west to Bourbon County, Kentucky—certainly a coincidence of the name.

How our Shurtleffs might have returned to the United States was suggested in a letter written by Lothrop’s eldest daughter (and Samuel’s eldest sister), Helen, to Benjamin Shurtleff sometime in the late 1800s for his work on his family genealogy (see Descendants of William Shurtleff, by Roy Shurtleff, 1976, p. 182-83):

When I wrote you some of my reminiscences I had been thinking of the Eastern Township as I first remembered the country, so far from any commercial or manufacturing center; the remoteness

and stillness of it make me lonely when I think of it. Only two years ago the township celebrated the centennial anniversary of their first settlement. Seventy years ago next summer the mail carrier went by twice a week; he always galloped his horse and blew a horn when near the house. He wore a sash wound about his person and carried a large green bag. Sixty-three years ago we lived in Charleston village, Hatley, and the great excitement, the one incident of their lives was the coming of the stagecoach with four horses; and the flourish of that terrible whip as the “Jehu” deposited the mail and then with such awful feats of turning, curving and prancing drew up before the one tavern in the full gaze of all the gaping, wondering loafers in the place with a sprinkling of anxious, earnest men, while we children looked through the gate on the other side of the street.

I left Canada in 1843. A great change has come to (the] country and people since I knew it. We had to travel 100 miles by stage to Burlington Vt., or to Montreal before we could take a boat to Cayuga Co., N.Y. All the way by water from Burlington to Whitehall on Lake Champlain, steamboat by the northern canal to the junction at Troy, N.Y, from there to Weedsport on the Erie canal. I have been over this slow route twice and twice down the St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario [emphasis added]. I am glad I have had all this old fashioned experience. I am glad too that I have taught a district school and boarded around. I am sadly crippled and can only hold a pencil in the ends of my fingers. No one who sees my hand and arm will believe I can write a word and it looks awkward enough to me. I cannot read all the time and I am thankful for everything that makes me forget myself and my suffering.

In those days, before the advent of the railroad in the area, travel by stagecoach and water was common. It seems likely that Samuel and siblings left Quebec by water, traveling westward up the St. Lawrence River into Lake Ontario. This was to mark the beginning of a lifetime of adventure together.

Wolcott, New York. Their first stop was undoubtedly on the south shore of Lake Ontario in Wolcott, Wayne County, New York. Here, since 1843 and for most of her life, lived Samuel’s remarkable elder sister, Helen, who had married Aaron De Witt Forman on 11 March 1846 in nearby Cato, Cayuga County New York. On the shore of Lake Ontario she established something of a refuge for this branch of the Shurtleff family and began a tradition of family solidarity that seems to have been one of the family’s enduring qualities.

The 1860 U.S. census for the town of Wolcott, Wayne County New York shows: Dewitt Forman (age 37, farmer, head of household) and his wife, Helen, age 38. Living under the same roof are: two of her younger sisters, Alice Jane Shurtleff (age 19) and Mary Elizabeth Shurtleff (age 16). Clarence L. Shurtleff (age one), the infant son of Asaph William Shurtleff, who is Helen’s younger brother.

Asaph (who was baptized William Shurtleff and also used the name William Asaph Shurtleff), following the death of his young wife, Kate Crockett, in 1859 in Bourbon Co., Kentucky, brought his ailing year-old son, Clarence Lothrop Shurtleff, to Wolcott to be under the family’s care. The rest of Asaph’s story is told below under “Bourbon County, Kentucky.”

The 1865 New York state census for Wolcott shows Dewitt and Helen Foreman living together alone in their house. In the adjacent house live Robert Foreman and Alice, his wife.

The 1875 New York State census for Wolcott shows five people living in that house. In addition to Dewitt Forman and his wife, Helen R. (both age 53), are James Forman (age nine, their son, born in Michigan), Clarence Shurtleff (age 14, nephew; see 1860 census), and Ruth [Little] Shurtleff (age 77, Helen’s mother). We are sur-prised to find that Helen and her husband, thought to be childless, have a son, James Forman.

In the house next door are Robert Forman with his wife (Alice), two children (Cynthia and Samuel), two nieces (Clara and Mariette Shurtleff), and his aunt (Ann M. Dewitt). In the house next to Robert are Tyler and Lucie [Lucia] Hyndman and their family.

The 1880 census shows living in Wolcott—not under one roof but in adjacent houses on the same street—Helen, her sister Alice, and, next door to her, Samuel’s (and Helen’s) sister Lucia. Her brother Solon’s first son, Amos Johnson Shurtleff, was born there (in Cato) on 13 July 1849.

We also learn that James Forman (son of De Witt and Helen), now age 14, is an adopted son with the middle initial “S.” Occupation: “Hard work.”

Also surprising is the information that Samuel’s elder sister, Lucia Hyndman (in a different household), had an adopted daughter, Mattie, age four. These two family members (James and Mattie) are not listed in Roy Shurtleff’s genealogy.

In Wolcott, Helen’s mother, Ruth Little Shurtleff, spent her last days, as did Helen’s husband, De Witt Forman, sister Lucia Sultana Hyndman, and Lucia’s husband, Tyler Hyndman. Lucia died on 2 September 1882 in Wolcott at age 55. Ruth died on 16 December 1882 in North Wolcott at age 85 and was buried in the North Wolcott Cemetery. Aaron De Witt Forman died on 26 April 1883 in North Wolcott at age 60. Tyler died on 20 September 1902 in North Wolcott at age 80.

For whatever reason (perhaps after the death of her mother in 1882 and of her husband in 1883), toward the end of her apparently warm and dedicated life, Helen left the family enclave in Wolcott and, nearly 20 years later, followed her siblings across the continent to Nevada City. There, brothers Samuel, Thomas, and their families had already established another homeland, where these and many other Shurtleffs would later set¬tle. Helen, the eldest of Samuel’s brothers and sisters, and mother-apparent to them all, died in Nevada City at the home of her brother Thomas on 17 February 1896. She was 74 years old. There is no known record of what happened to either her or Lucia’s adopted children.

Bourbon County, Kentucky: Samuel Marries Varilla Marston. Returning to the travels of Samuel and these early Shurtleffs: In the mid-1850s Samuel, his brother Thomas and Thomas’ wife Mariette, and their brother Asaph William Shurtleff all departed Wolcott for Bourbon County Kentucky. They may have traveled by steamboat west on Lake Ontario and through the newly constructed Welland Canal into Lake Erie, then to Cleveland or Toledo. From there they could have traveled by river to Lexington near Paris, Bourbon County, where in the 1850s the four Shurtleffs settled and began another gathering of the clan in Kentucky.

Thomas and Mariette’s first son, William Taylor Shurtleff, had been born on 9 July 1853 in Hatley, Quebec. However their second son, John Thomas Shurtleff, was born on 7 June 1857 in Bourbon County Kentucky. Thomas and Mariette seem to have remained in Kentucky for only a few years, before they returned to Quebec.

In the 1860 U.S. census for Bourbon County, Samuel and brother Asaph are listed as “school teachers” while Thomas, by that time back in Quebec, is not listed. However, records show Thomas also was teaching school there in 1853. Of Lothrop’s eleven children, four, including Helen and brothers Samuel, Thomas, and Asaph, were all school teachers, and two, Solon and Mary Elizabeth, followed in their father’s foot¬steps to become medical doctors!

Mary Elizabeth, the youngest of the 11 children, married Ludo Burrill Little on 2 January 1865 in Bourbon County Kentucky. He was born on 24 October 1838 in Lyman, New Hampshire, the son of Joseph Little and Mary Cobleigh. A year later, on 1 October 1866, their first and only child, Hazen Jesse Little, was born in Sterling, Cayuga Co., Kentucky. On 2 October 1871, a married woman with a five-year-old son, Mary Elizabeth registered for classes as a junior at the Medical Department of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. On 26 September 1872, she registered as a senior. On 26 March she graduated with an M.D. degree from the University of Michigan. It wasn’t until 1870 that women were admitted to this university’s medical department. Mary Elizabeth was one of the early women to graduate with an M.D. degree from an American university. Fortunately a photo taken during her student years (but undated) still survives in the “student portrait collection” of the university’s archives.

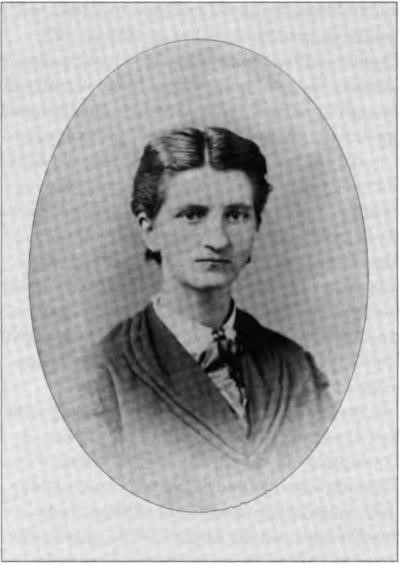

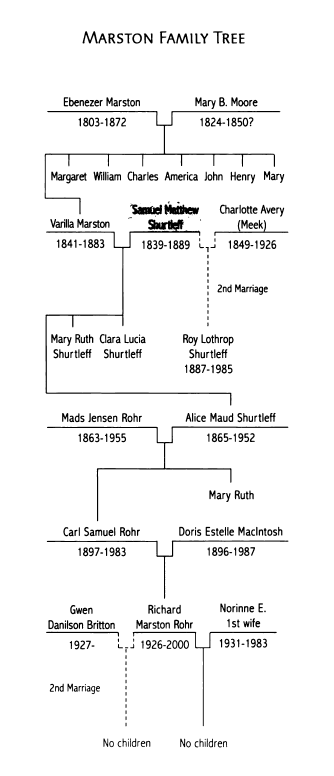

In August 1863, Samuel Matthew Shurtleff apparently married Varilla Marston in Bourbon County Kentucky—although we have been unable to find a marriage record. Her name was also spelled “Varille” and “Burrilla” in early documents. Samuel was a 24-year-old bachelor and Varilla was a 22-year-old Bourbon County belle. Born 28 May 1841 in Ruddels Mills, Bourbon Co., Kentucky, she was the eldest child of Ebenezer Marston and Mary B. Moore. Ebenezer was born on 31 January 1803 in Portland, Cumberland Co., Maine, the son of James Marston III and Elizabeth Cram. His first wife, Mary Moore, the daughter of Abraham Moore, had been born in about 1824 in Kentucky. In about 1850 Ebenezer married again, to Margaret Moore, and they had five children. Ebenezer was listed in the 1860 U.S. census for Bourbon Co. as a wealthy farmer from Maine.

Meanwhile, Thomas and Mariette were at home in Hatley, Quebec, where they had three more children: Flora Irvin Shurtleff, their third child and first daughter, on 18 April 1859; Clarence Asaph Shurtleff, on 22 March 1861; and Mariette Varilla Shurtleff, on 17 July 1863, a month before Samuel’s marriage to Varilla in Kentucky. Sometime earlier, in 1857 or 1858, Thomas, with Samuel, must have met Varilla Marston. Thomas obviously had found her attractive enough to name his own daughter after her, and Samuel found her attractive enough to marry.

An 1863 map, titled Map of the District of St. Francis — Canada East, shows Thomas (“T. Shurtleff”) owning two farms or dwellings in Lot 10, Range II of Hatley Township—west of Massawippi Lake. Many of the surrounding parcels are owned by people who are part of our story: Little, Hovey, Bean, Wadleigh, Bachelder, etc. In Compton Township, just to the East, Otis Shurtleff (1806-1872, Thomas’s second cousin) resides on Lot 18, Range VI.

Brother Asaph William and his young wife, Kate Crockett, were also in Paris, Bourbon County, Kentucky, where their first child, Clarence Lothrop Shurtleff, was born on 4 May 1859. Tragically, Kate died there about three months later, on 26 August 1859—probably from complications of childbirth. Then baby Clarence died a year to the month after he was born, on 16 May 1860 in Wolcott, Wayne Co., New York. Asaph had lost his wife and only child in less than a year. Two years later Asaph married again, to Louise Bevier DeWitt on 23 April 1862 in Liberty, Sullivan Co., New York. They had one daughter, Anna Louise Shurtleff, born on 10 August 1865 in Weedsport, Cayuga Co., New York. Asaph and Louise lived the rest of their lives in nearby Cayuga Co. She died on 9 May 1907 in Weedsport, Cayuga Co., New York. He died four months later, on 6 September 1907, in the same town. Both were buried in the Weedsport Rural Cemetery.

In about 1865 Mary Elizabeth Shurtleff, Samuel’s youngest sister, devotedly following her brothers in their travels, joined the group in Bourbon County. There in 1865, as explained earlier, she married Ludo Burrell Little. Their child, Hazen, was born in Kentucky and Mary Elizabeth later went on to become a physician in Michigan.

Brother Solon and his wife, Rebecca, also must have joined them in Kentucky, for their second child, Laura Helen Shurtleff, was born 22 August 1859 in nearby Wright’s Station, Kentucky. So in Bourbon County, Kentucky, another colony of Shurtleffs became established —Quebec, then Wolcott and now, Bourbon County. Thus this enterprising family that had ventured into the Canadian wilderness in the early 1800s almost unbelievably had headed south into what would soon be Civil War territory. During that war Kentucky became a “Union Slave State,” one that did not secede from the Union.

While still in Kentucky, Samuel and Varilla had their first child, Alice Maud, on 7 April 1865 and there, perhaps, their second child, Mary Ruth, on 24 April 1866. They were to become Roy Shurtleff’s half sisters, some 20 years his senior, whom he would come to know under very difficult circumstances many years later.

One member of this adventurous Shurtleff family seems to have gone his own way. Amos Shurtleff, the eighth child of Lothrop and Ruth (Little) Shurtleff, traveled (apparently alone) to the Deep South. In 1873 we find him in Texas where he married Mary Bringham on 11 December 1873 in Rusk, Cherokee Co., Texas. She was born on 29 May 1849 in Clayton, Barbour Co., Alabama. They had three children, all born in Texas. He died on 15 March 1883 in Wichita Falls, Texas. She died 55 years later on 22 Nov 1938 in Houston, Texas.

Normal, Illinois. In 1865 or 1866, for reasons that are not clear, Samuel, his wife Varilla, and daughter Alice Maud left Kentucky and journeyed the 200 or so miles to Normal, Illinois. A possible explanation for their departure could be that although Kentucky was a Union state, thousands of Kentuckians joined the Confederate Army, and by 1865-66 those who survived the war would be returning home. Thereafter the climate in Kentucky could have been extremely uncomfortable for the Shurtleffs, those “damned Yankees”—even “carpetbaggers!”

Normal (originally Junction City) was founded in 1850 at the intersection of two railroads, the Illinois Central and the Chicago and Alton. Daughters Mary Ruth and Clara Lucia were born there on 24 April 1866 and 28 May 1868, respectively. (Roy’s genealogy shows Mary Ruth born in Kentucky but the 1870 Illinois census records otherwise).

Of major significance to the story of Samuel Shurtleff is that, while in Illinois, he seems to have made his mark financially. Whereas only four or five years earlier in Kentucky he was a teacher, the 1870 U.S. census for Normal, Illinois, lists him as a farmer with land valued at $10,000 and other assets of $5,300, employing a maid for Varilla and three laborers for the farm. In 1870, by any test, Samuel appears to have become a well-to-do farmer—at the age of only 31. His future son, Roy Shurtleff (born in 1887), was apparently never aware of this financial success.

In Normal, once again the families began to reassemble: Following Samuel, the first to arrive in 1868 was his younger sister, Alice Jane Shurtleff, who married Robert Humphrey Forman on 18 May 1864 in Wolcott; he was probably the younger brother of Helen’s husband, Aaron De Witt Forman. On 17 July 1869 in Normal Alice gave birth to her only child, named Samuel De Witt, surely in a gesture of affection for her older brother Samuel.

Far to the west in Nevada City, in a surprising move, on 3 October 1872 brother Thomas sold his Piety Hill house, which he had purchased only three years earlier for Lodema and his five children. By 1873 Thomas, and probably son William, showed up in Normal, Illinois, and in the 1873 Bloomington-Normal city directory Thomas is shown as a partner in “Shurtleff and Bro. [S.M. and Thomas] Grain and Coal.” Our Samuel, the well-to-do farmer, was the senior partner with his older brother in the commodities business, and his nephew, William T., was their “salesman.” William married Melinda Dillon on 7 August 1873 in Normal, Illinois; she was from Delavan, Illinois. Their first child, born 5 July 1875, was named Mariette a tribute to his mother, Mariette Little Shurtleff, who had died in 1867 in Hatley, Quebec.

The partnership listing is the same in the 1874-75 city directory except for the addition of Thomas’s second son, John T., as a “clerk,” also from Nevada City, with the partnership. Thomas and his sons are shown living together on Walnut Street and Samuel living presumably with his family on “Oak between North and Ash.”

Then, most surprisingly, after only two years in the partnership with his brother, Samuel seems to have left town. At least the city directory for 1876-77 lists only Thomas, William, and John still living together but fails to list either Samuel or their partnership. On 21 March 1877 in Normal, Illinois, sister Flora Irvin married George Wyman Flint of Wolcott, New York, and soon returned to Nevada City. The 1878-79 city directory lists only son William T. now working as a clerk for Johnson & Chipman, indicating that Thomas, as it turned out, had also departed for Nevada City. The last of these Shurtleffs left Illinois by 1879, when William returned to Nevada City with his wife Melinda and daughter Mariette.

The sequence of events in Normal, Illinois, leaves us with perplexing and unanswered questions: What could explain Samuel’s newfound wealth as a farmer, his expansion into the grain business with Thomas, and then his seemingly sudden disappearance—all in such a short period of time?

Recall that in 1863 in Kentucky, Samuel had married Varilla Marston, daughter of Ebenezer Marston, listed as a wealthy farmer, age 46, born in Maine. Could this wealthy farmer have given, or even loaned, his son-in-law money to buy this farm, to hire farmhands and even a maid for his daughter?

Also, recall that the 1870 U.S. census for Nevada City shows his brother Thomas in the grocery business with total assets of $9,000, while in the Illinois 1870 census referred to above, brother Samuel is shown in Illinois with total assets of $15,350. Since Lothrop, father to both of them, had died in Hatley, Quebec, in 1862, could they have inherited money from their father, the surgeon? Or could there have been other wealth in the family, perhaps through marriage?

What happened to Samuel’s $15,300, his farm, and his partnership with brother Thomas? Why did he leave Normal before the others? Where did he and his family live between 1875 and 1878, when his name first appears on the voting list in Nevada City?

Why in 1872 did Thomas and his family leave their well-established home in Nevada City to join Samuel in Illinois? Did Lodema and his younger children accompany him or did he leave them behind in Nevada City as he had left his first wife, Mariette, and their children alone in Quebec some fifteen years earlier? These are subjects for further research.

Nevada City, California. Here in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada was the mother lode: the discovery of gold in early 1848 and the Gold Rush in 1849. Here, also, was the last concentrated colony of these westward-bound Shurtleffs—who came, if not for gold, for the love of adventure and family.

The first Shurtleffs to arrive in California came during the Gold Rush of 1849. Benjamin Shurtleff, M.D., a graduate of Harvard University, arrived in San Francisco on 6 July 1849, via a ship that sailed around Cape Horn. He joined the Gold Rush, and was later a fairly famous physician in Mt. Shasta, California, and a state senator from Shasta County in 1861 and 1863. George Augustus Shurtleff, M.D., also arrived in 1849. He went to Stockton, California, where in 1856 and again in 1863 he was appointed a director of the California State Insane Asylum, and in 1865 was elected medical superintendent of the same. Lucius Elderkin Shurtleff (a grandson of Asaph Shurtleff and Rachel Elderkin) was in California (Nevada City) by 21 October 1850 (see Roy Shurtleff, 1976, p. 133, 236-37, 311). None of these three men, however, were our direct ancestors.

In 1863, Thomas Shurtleff was the first such direct ancestor to arrive in California, probably from Quebec where, in the 1861 census, he was listed as a farmer; he probably remained in Quebec with his wife, Mariette, until 1862, when his father, Lothrop, died—or until 1863, when their last child, Mariette Varilla, was born there. He then appears to have left his wife and family in Quebec when he headed west to California.

According to the History of Nevada County (1880, Thompson & West), Thomas arrived in Nevada City in 1863. He worked in the dairy business until 1865, then worked for another firm, Gregory and Waite, until 1867. His residence in Nevada City was on the prestigious Piety Hill. He seemed to have been well on his way to establishing himself as a productive citizen in his chosen home, but as subsequent events will reveal he had even bigger things in mind.

For the four years from 1863 to 1867, when Thomas was in Nevada City, Mariette was in Quebec with her five children. Now that Thomas had a good job and established a home of his own, the time seemed at hand for his family to join him in California—but it was not destined to be.

In Quebec, Mariette Little Shurtleff, his wife of only 15 years, died on 9 October 1867, leaving five children ages 14 and under without a mother and with their father in faraway California. She was buried there two days later in the Adventist cemetery. At that point Thomas seems to have left his California employer, Gregory and Waite, and returned to Quebec to retrieve his children and escort them to their new home in Nevada City. Son Clarence, as reported in the 27 November 1937 Grass Valley Union, had crossed the Isthmus of Panama with his father, Thomas, when he was “about five years old.” The History of Nevada County shows son William coming with his father in 1867. It seems Thomas had returned from Quebec to Nevada City with all of his children.

Only a year later, Thomas, now widowed and age 38, married Lodema Caroline Percival (age 25) on 16 September 1868 in San Francisco, California. Born on 11 June 1843 in Hatley, she was the daughter of Charles Lewis Percival and Emily Kezar.

Meeting and marrying a fellow native of Hatley, Quebec, in San Francisco so soon after his arrival could have been pure coincidence, or Lodema might have been taking care of Mariette in Quebec before her death and also caring for Mariette’s children. If so, while still unmarried, she and her brother 0. C. Percival, who shows up soon after as a resident of Nevada City, may well have accompanied Thomas, to care for his five children on the long sea voyage to California.

Married again and back in Nevada City in 1868, Thomas was in a partnership, Shurtleff & Baldwin, and by 1869 had bought his house on Piety Hill. By 1871 he left Baldwin and established his own business. The Nevada City county directory displays an advertisement for “Thomas Shurtleff, Dealer in Groceries, Provisions, Case Goods, etc. Junction Main and Commercial St., Nevada City.” He was now a town trustee.

The 1870 U.S. census for Nevada City shows as living there, under one roof, Thomas, his wife Lodema, their five children, and, surprisingly, his older brother Solon, working for Thomas as a clerk. Solon, who obtained his M.D. degree from Geneva Medical College in New York and passed his medical examination in Toronto, began his medical practice in 1853 at Massawippi Village in Hatley, Quebec. He became a successful physician in Quebec. Recall that by 1859 he was with his sister, Helen, in Bourbon County, Kentucky. His obituary indicates that ill health in Canada caused him to look for a better climate. In Nevada City he finally rallied briefly and tried to farm but died on 19 February 1871 near Nevada City at age 46. According to the same census, brother Samuel had apparently not yet arrived in Nevada City.

Recall that Samuel Shurtleff’s last known whereabouts, according to the 1874-75 Bloomington-Normal City Directory, was as a senior partner with brother Thomas in that city. The following year his name and his partnership are no longer listed in the census and his whereabouts is a mystery. Finally, in 1878, Samuel shows up in Nevada City. That year his name appears for the first time on the voter registration sheet—and he is working as a “clerk” for [Thomas] Shurtleff and Jamieson.

Then, surprisingly, the Nevada County Deeds book shows that on 21 December 1878 Samuel M. Shurtleff and John T. Lewis purchased a small piece of commercial property on the corner of Main and Coyote Streets, with a brick building on it, for the astonishing price of $7,524 in gold coin. Astonishing not only for the extraordinary amount of money but also because only one year before, in November of 1877, brother Thomas had purchased the same property for only $500 gold. Nine months later Thomas sold it to B. W. Regan of Alameda County for $4,100 gold. Then only four months later Samuel and Lewis paid Regan 15 times what it had cost brother Thomas only a year earlier. This unusual transaction would have occurred only months after Samuel, under unexplained circumstances, left his brother Thomas and their partnership in Illinois.

Nothing is known of Samuel and Lewis’s business in the brick building, but we do know that on 5 January 1880, just one year after his $7,524 purchase, Samuel sold half of his interest to Thomas’s two sons for only $250. Nine months later, the two, William T. and John T., both of whom had worked for Samuel in Illinois, sold their interest for $800. It is not known whether Samuel and Lewis’s costly venture ever got started or if it was just a very bad real estate investment. In any case, by 1880 the money seems to have been lost and Samuel was again a grocer probably working for or with Thomas. Perhaps he had never left his job with Thomas as he may well have understood the risks involved in starting a new partnership in a new city and, meanwhile, wanted to protect his income.

Still more money seems to have been in Samuel’s family when on 20 October 1879 his wife Varilla, in her own name, purchased for $1,400 two residential parcels, on Gethsemane Street on Piety Hill across the street from where Thomas and Lodema had lived. This purchase suggests that Varilla and Samuel’s money could have come from her wealthy father, as well as from their farm in Illinois.

The 1880 U.S. census for Nevada City shows Samuel in this newly acquired house with Varilla and their three children. His occupation is listed as “grocer”—he is obviously no longer a prosperous farmer in Illinois.

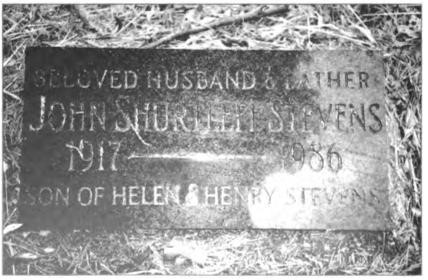

In 1881 Thomas and his second wife, Lodema, had their first child together, and his sixth child. Helen Emily Shurtleff was born on 3 June 1881 in Nevada City, California. She later married Henry Cushing Stevens (11 May 1904 in Cloverdale, Sonoma Co., California).

On 5 January 1883 Varilla, Samuel’s wife of almost 20 years, died. Her obituary in the Daily Transcript cites the cause of death as “paralysis of the spinal column—a lady of estimable qualities, a devoted Christian with the love and respect of all who knew her.” She was 41 years, 9 months, and 11 days old. Only two years after Varilla’s death, their youngest daughter, Clara Lucia, died, also in Nevada City. Samuel and his two remaining daughters, Alice Maud and Mary Ruth, continued to live on Gethsemane Street, the same property Varilla had purchased for the family four years earlier.

Then on 1 December 1885 Samuel and his two daughters sold one-half of the large lot on which they were living for only $300 gold coin. Land prices in the gold country, it seems, were beginning to fall.

Samuel and Varilla Shurtleff had three daughters—Alice Maud, Mary Ruth and Clara Lucia.

- Alice Maud Shurtleff was born 7 April 1865, Bourbon County, Ky. On 19 Dec. 1895 she married Mads Jansen Rohr in Nevada City. He was born near Jordan, Denmark, 9 Dec. 1863 and died 20 June 1955 in Danville, Illinois. Alice Maud died 4 Feb. 1958 in Carmel, California.

- Mary Ruth Shurtleff was born 24 April 1866 in Normal, Illinois, according to the 1870 Illinois census (Roy Shurtleff and family genealogy gives her birthplace as Bourbon Co. Kentucky, probably in error). She married Henry Conrad Weisenburger in Nevada City on 6 March 1889. He was born 2 Feb. 1864 in Downieville, Sierra Co., California, and died 28 May 1946 in Watsonville, California. They had one child, a daughter, born 19 Sept. 1890. She died in about 1985 in Watsonville, California.

- Clara Lucia Shurtleff was born 28 May 1868 in Normal, Illinois, and died unmarried 22 Feb. 1885 in Nevada City just three years after her mother, Varilla, and four years after her father, Samuel. She was 17 years old.

Alice Maud Shurtleff and Mads Rohr of Demark had two children. Mads had evidently come to Nevada City, met Alice, and decided to marry and remain there. In any event their two children, Carl and Mary Ruth, were both born there.

- Carl Samuel Rohr was born 19 Jan. 1897 in Nevada City. On 24 Jan. 1925 he married in Seattle, Washington, Doris Estella Macintosh, who was born 6 Nov. 1896 in Bellingham, Washington, of Horace Albert and May Gertrude Walker. Carl was a master electrician and is said to have wired most of Carmel’s houses in the early 1900s. He died at his son’s home in Ventura in about 1983. His wife died in about 1983.

Carl was a half cousin to Lawton, Gene, and Nancy Shurtleff, sharing as they did the same grandfather, Samuel Shurtleff.

The close relationship between the Rohr, Weisenburger, and Marston families is shown in the “Centennial Farm Application” for the “Rohr-Weisenberger Farm” located at R.R. 3, Hoopeston, Illinois. The 480-acre farm was originally pur¬chased by William Marston on 11 May 1867. The successive owners were: John and Mary Marston (brother and sister), from 22 Aug 1929, Alice M. Rohr and Ruth Weisenburger (3 Dec. 1936), Alice Weisenburger (23 Dec. 1946), Richard M. Rohr and Carl S. Rohr (30 April 1951), and Richard M. Rohr (27 April 1984).

This history is intriguing since this farm in Hoopeston is only 90 miles or so from where Varilla and Samuel farmed luxuriously in 1870, when Samuel was only 31 and Varilla only 29. Could the same uncle (or perhaps her father, Ebenezer) have deeded land to his two grand-children as he may have deeded land to Varilla?

Since Carl was an electrician and not a farmer, he and sister Mary Ruth used to lease the land for others to farm, and all the family continued to vacation there. Mads died in Danville near where he had been vacationing with Carl and Doris at the Hoopeston farm. Carl and Doris had one son.

Richard Marston Rohr was born in 1926 in Pacific Grove, California, and died on 14 Jan. 2000 in Carmel, California. His second wife, Gwen Britton Rohr, described how Richard was persuaded by his grandfather, Mads, to study agronomy so he could take over the Hoopeston farm in which he then owned shares. But farming never appealed to the Rohrs so after Richard’s death it was sold. Gwen still lives in Cannel where she and Richard and his parents had lived all their lives. Gwen and Richard had no children.

Image – The late Richard Rohr and his second wife, Gwen Britton Rohr, in Phoenix, Arizona May 1993.

- Mary Ruth Rohr was born of Alice Maud and Mads Rohr on 11 April, 1899 in Nevada City, California On 6 Sept. 1924 in Palo Alto she married David Pringle Williams, born 1 April 1893 in Purdy Station, New York. Mary Ruth died 9 Jan. 1949 in Cannel, California, and her husband died in Santa Cruz, California, in June 1962. The Williams had one child, a boy.

Marston Harvey Williams was born 26 March 1929, in Azusa, California. Richard Rohr was in contact with his cousin Marston in their younger days but, according to Gwen Rohr, ultimately lost track of him. It is not known if he married or had children, or where he lives. A search of the phone records for the entire west coast from Alaska to Hawaii shows no Marston Harvey, and none of the Harvey Williamses listed and contacted know of the Marston name.

Following Varilla’s death, life must have been very difficult for Samuel and his three daughters. At the time of their mother’s death in January 1883 Alice was 17, Mary Ruth 16, and Clara Lucia 14. For the next two years, the three young ladies presumably were in complete charge of their home on Gethsemane St.—purchased using their mother’s money in 1879. Following Clara Lucia’s death in February 1885, the two remaining sisters ran the home until 1885 when their father remarried.

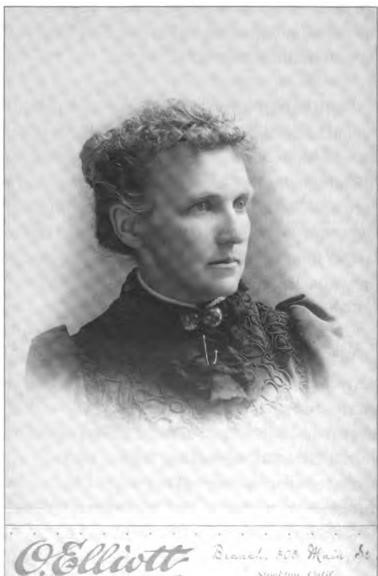

On 6 December 1885, just short of three years after their mother’s death, their father, Samuel, married Charlotte Avery Meek, age 33. Moving into Samuel’s (Varilla’s) home with her were her three children, Jessie (age 16), Nettie (age 5), and possibly her eldest child Charles (age 17). So instead of a family of three Shurtleffs in the house that Alice and Mary Ruth were managing, there were suddenly, with the appearance of the four Meeks, a total of seven.

Image – Charlotte and Samuel Shurtleff in about 1885. Thought to be taken at the time of their marriage—from Roy Shurtleff’s family collection.

Then on 19 September 1887 Samuel and Charlotte’s only child, Roy Lathrop Shurtleff, was born in that same household. In giving his son the middle name of “Lathrop,” Samuel was obviously trying to honor his own father, Lothrop, but the spelling was wrong. Years later, when Roy learned the origin of the name, he had his own name changed to “Lothrop.” What hectic days those must have been—ending up with eight in-laws all under one roof. Who would have been managing the house, and what was the relationship of the two daughters and their new mother-in-law?

On 30 May 1888 Samuel was involved in a tragic accident that would forever impact the lives of Charlotte and her young son.

Only a few months before Roy’s first birthday, and less than three years after his marriage to Charlotte, Samuel was driving his wagon and a team of horses along a toll road and bridge crossing the South Fork of the Yuba River several miles outside of Nevada City when tragedy struck. The Daily Transcript (Nevada City) of 1 June 1888 (Friday morning, p. 2, col. 3), under the title of “A shocking accident: S. T. [sic, M.] Shurtleff and Mrs. Lynch badly hurt on the Edwards Grade,” wrote:

Last Tuesday Samuel T Shurtleff of this city went to the upper part of the county with a four-horse wagon loaded with vegetables, fruits, etc. Having disposed of his produce, he started to return Wednesday [May 30] with Mr. And Mrs. Lynch who have been residing at Malakoff, also their house furniture, chickens and other personal effects. Mr. Lynch had secured employment at this city and was moving down. They came along all right till they were ascending the grade at the first turn a quarter of a mile this side of Edwards’ toll-bridge, when some Chinamen who were on the hillside above cutting poles with which to flume the river let a piece of timber get away from them and it came sliding down the declivity striking between the legs of the lead horses. The team taking fright “jack-knifed,” that is turned short in the opposite direction. The wagon tipped over, throwing the people and the articles aboard over the edge of the bank, which is walled up there, to the foot of the wall 25 or 30 feet below. The horses ran down the grade, leaving portions of the wagon here and there, crossed the bridge, then ran up the north grade till they reached the watering trough where they were caught by some freighters. Mrs. Lynch and Mr. Shurtleff were badly hurt by their fall, Mr. Lynch being but slightly bruised. The son and daughter of Mr. Edwards hurried to the scene of the accident as soon as the team passed their house, but the Chinamen responsible for the accident had been there first, removed the pole that scared the horses, then ran away without letting the victims or anyone else see them, or offering any assistance. The injured people were, with the help of Wm. Cole and others who came along, taken to the toll house and word of the mishap was sent to town. Dr. H. S. Welch and Dr. Little (the latter being Mr. Shurtleff’s sister [probably Mary Elizabeth Shurtleff, wife of Ludo B. Little]) with others went out at once. Mrs. Lynch was badly bruised, jammed and wrenched; hut it cannot yet be told whether she is fatally hurt. None of her hones were broken. She was brought to town yesterday. Mr. Shurtleff’s right hip is fractured just below the joint, and he is also much cut and bruised. He was brought to his home the evening of the accident. Both of them sutler intense pain and are in feeble condition.

The gruesome details of the accident are described in a lawsuit, Court file 41538, tiled by Samuel and his attorney against one William Edwards, the owner and operator of the toll road and bridge. They claimed negligence in the maintenance and operation of the road and asked $10,000 for injuries and loss of Samuel’s ability to support himself and his family. Parts of the suit read as follows:

and while said plaintiff Samuel and the team he was driving were carefully traveling upon said wagon on Toll-Road the defendant—permitted parties to carelessly and negligently cut poles and trees above said Toll-Road causing a large peeled tree or pole to be suddenly thrown down—immediately in front of the team and vehicle the plaintiff was driving to become scared and frightened and unmanageable and by reason of said fright to the team, the vehicle upon which the plaintiff was riding—was suddenly overturned and broken apart—The said vehicle – falling upon said plaintiff and dragging him beneath it crushing and mangling the person of plaintiff—whereby plaintiff was greatly injured—and is now and will forever hereafter be partially or wholly incapacitated from performing manual labor.

This document was signed “Samuel M. Shurtleff” in a handwriting almost identical to the now familiar signature of his son Roy Shurtleff. The defendant’s case was:

that the trees were being cut and were falling from land owned by the Central Pacific Railroad, that Samuel’s horses were not an ordinarily gentle team—and that, in any case, Samuel had not suffered serious injury and that injuries suffered have been greatly exaggerated for the purpose of securing extortionate damages from the defendant—denies he has been put to any expense whatsoever for medical or surgical treatments.

If Samuel had any hope of receiving $10,000 or any part thereof from this suit, he was to be bitterly disappointed. The jury of 11 men on 26 December 1888 found for the defendant and against Samuel, assessing him a total of $71 for miscellaneous costs. What a sad Christmas present.

The apparent injustice suffered by Samuel was indicated by the following “Personal Mention” column printed 2 June 1888 by the Nevada City Daily Transcript, only three days after the accident:

The fracture of Samuel T [sic] Shurtleff’s hip was reduced yesterday by Drs Little and Jones for the second time, the bone having slipped out of place the night before. In the afternoon he was resting easily, but was feeble. Mrs. Lynch, who was injured at the same time Mr. Shurtleff was, is considered out of danger.

The sad fact is that only eight months later Samuel died at his home from pneumonia resulting from the seriousness of the accident. Following his death, obituaries paid tribute to Samuel and reference the cause of his death.

From The Daily Transcript (Nevada City), 27 August, 1889:

Death of S.M. Shurtleff

Samuel M. Shurtleff, City Assessor, died about 5 o’clock Saturday morning at his home on Piety Hill. He had been ill for a week with pneumonia. The funeral took place Monday afternoon under the auspices of Nevada City Council; No. 178, order of chosen friends, in which organization his life was insured for the some of $3,000 in favor of his children. The deceased leaves a wife, two daughters and an infant son. He had been a resident of this city for about 15 years past, and was for a long time engaged in the grocery and provision business here. Last year he was severely injured by an accident which occurred while he was traveling on the road between this city and Bloomfield, and since then he has been in feeble health. Mr. Shurtleff was a man of intelligence and energy. A large circle of friends will mourn for him.

From the Grass Valley Union, 25 August, 1889:

Death of S. M. Shurtleff

S. M. Shurtleff of Nevada City, died yesterday of pneumonia after a brief illness. He was severally [sic] injured about a year ago by his team going over the Edwards grade, on the South Yuba River, and had never been strong since that time. His widow was Mrs. Meek of this place.

Back in March 1886 Charlotte, then two years married to Samuel and just before his injury, had bought for $500, in her own name, a triangular piece of property, also on Piety Hill, and only two lots from where she was living with Samuel and stepdaughters Mary Ruth and Alice Maud (Clara having died the year before). She was already carrying her only child by Samuel and she may have anticipated problems yet to develop. In fact, that same son, Roy Shurtleff, recalled later that the two stepdaughters, after their father’s death, had forced Charlotte out of the house they considered their own and hardly ever spoke to her again. Twelve years later Charlotte would sell her interest in this property for a mere $1 gold.

On 1 April 1888, only a month before Samuel’s injury, Charlotte splurged again, this time purchasing for $1,250 gold a very large lot close to town between Court and Coyote Streets only a block or so from where Samuel and Lewis had bought their ill-fated brick building a year earlier. So Charlotte, on her own, was investing in land as prices, in hindsight, appeared to be falling. This property was sold, part in May of 1908 and part in 1909, for a total of only $20 gold. Five years later, in June 1894, perhaps in a desperate financial gamble, she purchased a commercial property, formerly the law offices of John T. Caldwell, for $1,675. She then seemed to have sold it 8 January 1896 for only $500. These must have been discouraging losses for a mother who had lost two husbands in only six years and, once again, was on her own with young children to support.

All of the above indicates that in the Shurtleff family in the mid-1880s there seemed to be plenty of money. Where it all came from is not clear. Thomas and Lodema obviously had their share. Varilla and Samuel had theirs. Charlotte seems to have had money, perhaps from her first husband John Meek, the pharmacist, or even possibly from Samuel. Sadly, by the late 1880s and early 1890s, land in the area had lost a great deal of its value.

Between Samuel’s apparent loss of his business and Charlotte’s in her land speculations, they appear to have lost more than $10,000 in gold, the equivalent today of approximately $200,000.

The financial panic and stock market crash in June 1893 and the long depression that followed are described as the worst in the United States until the 1930s: 600 banks failed, 1,500 businesses closed their doors, and 74 railroads went into receivership. By 1895 European investors had withdrawn so much gold from the United States that the country (which had no central bank at the time) was almost forced off the gold standard; it was saved only when J. P. Morgan stepped in boldly in 1895 and, with other New York banking houses, loaned their government $65 million. The depression of the 1890s also brought hardship and suffering to Samuel’s family. His son, Roy, would later come close to financial disaster himself in an even larger crisis—the Great Depression of the 1930s.

For Charlotte, with most of her money in nearly worthless property, these were difficult years as she worked and scrimped to support herself and her family and to save for her family’s future. It was always her fondest hope that her children could receive a college education. In fact in 1898, when daughter Nettie was ready for college, Charlotte, Nettie, and Roy left Nevada City to settle permanently in Berkeley near the University of California. As part of the move, and for whatever reason, she sold the property on Piety Hill that she had bought for $500 for the discouraging sum of $1 gold. While living in Berkeley she sold her last remaining properties in Nevada City. In 1908 and 1909 she divided the large parcel in downtown Nevada City that she purchased in 1888 for $1,250 and sold it for a total of only $20.

Looking back on Charlotte’s life with Samuel, it is easy to see that despite early successes, it ended badly financially. While we do not know the facts about the Shurtleff and Lewis partnership and their $7,525 investment, it would appear that Lewis got out with $300 and, ironically, Thomas’s, sons, William and John, got out for $800. There is no evidence that Samuel got out with even so much as a dollar. The next thing we know, he was working as a “grocer” in Thomas’s general merchandise store.

In Roy’s later life, his interest in the Shurtleff family led him to years of research and writing, culminating in his publication on 4 July 1976 of his two-volume genealogy, Descendants of William Shurtleff. Despite Roy’s twenty years of researching and writing about his family, he seems to have known almost nothing about his own father’s life or the lives of his fascinating family. A description of his early childhood in Nevada City (written 3 January 1941 for his son Lawton’s diary) strangely fails even to mention his own father. Roy’s sons, Lawton and Gene, and daughter Nancy recall hearing almost nothing about their grandfather except as Roy writes briefly in his 1976 genealogy (p. 488): “My father died when I was less than three years old so I was raised by a frugal, religious and loving mother who was ambitious for her children.” (Actually he was less than two years old. Samuel died in 1889, not 1890, as Roy had believed.)

Son Gene writes that he recalls Roy telling him almost ruefully: “Dad [Samuel] was never successful—worked at several jobs.”

Despite this, his will included a $3,000 life insurance policy for his children equivalent to some $60,000 today. This meant his own three children, Maud, Ruth, and Roy, each would have had the equivalent of $20,000. These are admirable achievements for a man having lived only 15 years in this frontier town in the Wild West. A man of great financial success himself, Roy would have been surprised and pleased (and also curious) to have known of his father’s full and varied life, including a seemingly very successful farming endeavor in Illinois and a senior partnership there with brother Thomas in the grain and coal business—and saddened by its ending.

Son Gene remembers a trip with Roy to Nevada City in 1963, when Roy was 76 years old and Gene was 45. Roy showed Gene the family home (probably Varilla’s) on Gethsemane Street on Piety Hill and also the much more modest home they had lived in following Samuel’s death when his daughters forced their stepmother, Charlotte, with one-and-a-half-year-old Roy and his sister Nettie, to leave the house their father had owned before Samuel had married her. From that time on Roy remembered that Charlotte barely talked to his half sisters, but he found them to be quite pleasant. Roy also showed Gene the Shurtleff family burial plot with its aging Shurtleff curbstone probably purchased by Charlotte with the help of her brother-in-law, Thomas, or others of the family.

Located at the corner of Boulder and Red Dog Streets, the Pine Grove Cemetery with its large trees is obviously old and still well maintained. There in the family plot are buried Roy’s father, “Matthew Samuel Shurtleff (1839-1890);” his first wife, Varilla Marston (1841-1882); their youngest daughter, Clara Lucia (1868-1885); Samuel’s sister-in-law, Lodema Caroline (18431896); and Thomas and Lodema’s child and Roy’s cousin, Helen Emily Shurtleff Stevens (1881-1965). All this is inscribed on a black granite gravestone, which Roy purchased and is now prominently displayed under a large cypress tree in the Shurtleff plot. (Roy was following Benjamin Shurtleff’s erroneous dates for the death of his father, actually 1889, and Varilla, in 1883.)

Two smaller stones have since been carved with Helen Emily’s husband’s name, Henry Cushing Stevens, and the name of their son, John Shurtleff Stevens. These were placed by John for his father Henry and for John by his widow, Betty Stevens, now living in Sonoma, California. Surely this was a close-knit pioneering family always on the move, seeking a better life, often moving together. This feeling of interdependence probably had its origins long ago in the wilds of Quebec where relying on family may have meant the difference between death and survival.

The Chardonnay story. Roy loved to tell the story of his older cousin, Mariette Varilla Shurtleff, Thomas’s daughter, who in 1882 in Nevada City married the young Frenchman Anselme Aristide. On their trip to Nevada City in 1963, Gene recalls Roy reminiscing about relatives he had visited there in his youth when he was less than 10 years old. He thought their name was “Chardonnay—or something like that.” They must have been very wealthy, for he remembers that they had a large home, owned a gold mine, and had planted mulberry trees in the hope of raising silkworms. It was for Roy only a vague recollection, but Gene remembers that even some 75 years later, Roy was able to find the small out-of-the-way road to the once elegant “Chardonnay” estate. Roy’s usually excellent memory triggered an interesting story.

A publication found in Nevada City, titled the “French Connection,” states:

In this story of the French connection in Nevada County, we must also mention French Hill, at Canada Hill, where a group of French-Canadians prospected in 1861, the better-known being Leopold Charonnat who owned “one of the best paying mines in the district.” Charonnat was a graduate of the French naval academy; he and his wife, Marie-Sophie Luton, were married in the Reims cathedral. A brother, Ernest, was “somehow connected with several South American gold mines.” Leopold and Marie Charonnat arrived in New York in 1850 aboard their own vessel., [emphasis added] which they promptly sold upon their arrival, and came to San Francisco where they became the owners of a hotel. By 1852 they were in Sacramento in the dry goods business “for a while,” and came to Nevada City in 1855, purchasing the mine which they operated until the early 1920s.

The Charonnats also planted mulberry trees with the intention of establishing a silk-making venture which eventually failed. To this day, there are fifth generation descendants of that family who maintain a plot at Pine Grove Cemetery in Nevada City. The family home still stands at the corner of Nimrod and Clay streets, where the Charonnat Mine was said to be the first in Nevada City to install a small water-driven plant that generated electrical power.

What Roy had recalled was the wealthy Charonnat family (not the Chardonnay of a young boy’s or a grown man’s fantasy) into which Roy’s cousin, Mariette, had married on

20 August 1882. Her husband, son of the French immigrant Charonnat described above, was Anselme Aristide Charonnat, born in Nevada City in 1850.

We have never understood why our Shurtleffs came to California in the 1860s, or why they settled in Nevada City. Is it not possible that in the mid-1800s rumors of the French Charonnats’ success in the California gold mines got back to friends in common in Quebec, where Thomas was living—and had been overheard there by Thomas, leading him eventually to seek his fortune in California? Mariette’s marriage into one of the wealthiest families in the region is surely part of the Shurtleff pioneering tradition, even if of a very different kind.

Certainly Samuel’s marriage in 1885 to the very attractive Charlotte Avery Meek, granddaughter of the Avanns, land-owning gentry from Kent County, England, who came to this country in the early 1840s, was another such fortuitous move. She was the daughter of the remarkable Maria Louisa Avery described in Chapter 3 above. It is a great credit to Samuel’s foresight that he courted and won a woman 10 years his junior and welcomed her and her children to join him under his roof and his care. And from that all too brief but fruitful union of Samuel and Charlotte, on 19 September 1887, their son and only child, Roy Lothrop Shurtleff, was born—a child destined to uphold all the promise of his adventurous and enterprising ancestors. Roy Shurtleff, undoubtedly inspired by his frugal and loving mother and the sacrifices she had made for his and sister Nettie’s college education, went on to become a greatly respected, highly successful entrepreneur in the investment banking business and an outstanding scholar and civic leader in San Francisco. Roy died in the St. Francis Hospital near his elegant home on Hyde Street in San Francisco on 15 June 1985. He was 97 years old (as described in Part III, following).

REFLECTIONS: WHY DID ROY KNOW SO LITTLE ABOUT HIS FATHER?

s we have researched the life of Samuel Matthew Shurtleff and his Shurtleff relatives, we have often asked ourselves why Roy Shurtleff seemed to know so little about his own father. After all Roy was a devoted family man, a scholar, and a genealogist himself.

His own mother, Samuel’s widow, Charlotte Avery Meek Shurtleff, was extremely close to her children until her death in 1926. At that time Roy was nearly 40 years old, and for the 12 years since the birth of his own first son, and before, must have had access to all Charlotte’s recollections of his father. Charlotte was active and alert until the day preceding her death. So all the information Roy might have sought for was probably readily available.

As described, Roy never mentioned his father to his own children except for the one reference to his son Eugene that “Dad was never successful—worked at several jobs.”

So why did Roy not learn more about his father from his mother? It is possible that Roy was aware of something in his own father’s life that was so unpleasant he elected not to pursue it further. However, given all we know of Samuel today, including his financial setbacks, that is an unlikely scenario since he and his family were active, enterprising, and decent members of their society.

A more likely explanation could have been his mother’s unwillingness or inability to recall and to tell Roy about that part of her life. As described in Chapter 5, Charlotte’s life with her first husband, John David Meek, surely seemed idyllic—in retrospect. As a 17-year-old young lady just out of a girl’s boarding school, almost alone in a new and still wild frontier town, she would have found real security in a devoted husband 12 years her senior. Not only was he her protector but he was also a successful provider for her and the three children soon to follow. Her beloved mother, Maria Louisa, brother Frank, and elder sister, Lizzie, were close at hand. limes were good and life must have been sweet.

Then suddenly and unexpectedly in 1883, after 17 years of marriage, John David Meek was gone. Soon her mother left for Santa Cruz and shortly thereafter her brother, Frank, married and also left for Santa Cruz. Once again she was mostly alone. Two years later, in December 1885, she married Samuel, who died only four years later. We don’t know how long she had known him, or what kind of a marriage he had with his first wife, Varilla or, finally, with Charlotte. We only know that Samuel died at home a very sad and painful death.

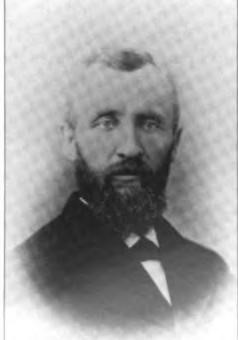

Left: Samuel Shurtleff in about 1885. He died 24 August 1889, two weeks after his 50th birthday from injuries received in a tragic horse and wagon accident.

Right: Young Roy Shurtleff, born 19 September 1887, was not yet two years old when his father, Samuel, died. So he would have no memories at all of his father — nor seemingly, did he ever try to learn more about this mostly forgotten ancestor—sadly for both. Roy’s earliest photo at six months.

For all these reasons —and with no attempt to assign any blame—it is certainly understandable for Alice, now some 34 years of age, and Mary Ruth, age 33, to have wanted their home back. Yet what a hurt and humiliation for Charlotte and her young children to be evicted from what she felt was her family’s home.

And lastly, of course, was the terrible accident that befell her new husband, after which he was confined to the house as a total invalid for over a year from the date of the accident in April 1888 until his death in August 1889. In addition, the financial losses she had suffered probably added to her unhappy memories.

A careful reading of Chapter 5 suggests that Charlotte’s memories of her marriage to Samuel were too painful to talk about. They may have been so bitter that she blocked them out of her memory.

If either scenario is true, Roy, out of compassion for his beloved mother, certainly would not have pushed further for information concerning the father he barely knew.

In early 1941, at the request of his eldest son, Lawton, Roy wrote (with pen and ink) a 17-page autobiography; he did not mention his father.

In 1962, shortly after his retirement and long after his mother’s death, Roy decided to become a genealogist, and to revise and update the two-volume Shurtleff family genealogy, which had first been published in 1912. Joining prestigious organizations such as the New England Genealogical Society, he learned a new set of techniques for finding out about one’s ancestors —

genealogical research. For the next 14 years he focused his attention on this huge project.

Why did Roy not learn more about his father using his new genealogical skills? Since he had never known his father, he now had a golden opportunity to learn more. If he had simply visited the library in nearby Nevada City California, where his father lived and died, he would have probably discovered most of the documents we have found. Yet there is no evidence that Roy made any effort as a genealogist to learn more about his father.

In 1976, when his prodigious, two-volume Descendants of William Shurtleff was published, there was no new information about his father. The genealogical entry for “Matthew Samuel Shurtleff” was identical in every detail to the entry that appeared the 1912 edition—except that he added his mother’s death date and the names of her parents. Unfortunately, he copied four errors, including erroneous death dates for this father (almost a year in error) and Varilla. He apparently didn’t even know that his father used the name “Samuel Matthew” throughout his life.

In this book, at his own entry (p. 488-90), Roy writes a brief autobiography. He says quite a bit about his mother but virtually nothing about his father: Mother “married my father, in 1885, and moved to Nevada City Cal., where I was born.”

Unfortunately we will never know Roy’s motivation—or lack of it—but only that it deprived him of knowing a father of whom he could have been proud, a father who died before Roy’s second birthday.